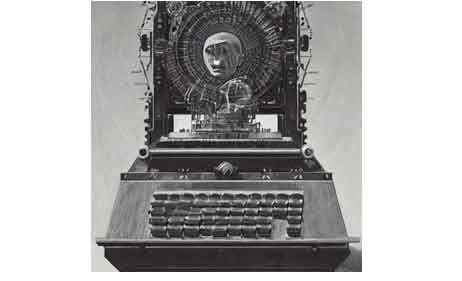

With the equally rapid developments of both artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics, perhaps one day, we might see a self-confident robot like the one seen in the 2004 Hollywood movie, iRobot. Such futuristic setups raise the question, will it ever be at all possible to equip machines with consciousness?

The answer to this question has something to do with what AI people call the C-word – consciousness, i.e. one’s awareness of one’s internal and external existence. One might argue that AI has achieved consciousness when it can answer Nagel’s famous question, what is it like to be a bat? The answer would need to reach beyond what ChatGPT can find on the Internet and can assemble in a semi-logical sequence to create a plausible-sounding response.

Meanwhile, another robot engineer might say, while sitting in a RoboLab, this topic was taboo … we were almost forbidden to talk about it … don’t talk about the C-word … or you won’t even have a job.

Yet, machine adaptability becomes more and more important the more we rely on AI machines. Nowadays, robots are used for surgical procedures, the production of cars and food, the transportation of goods, and so on. The application of AI machines is almost endless.

Furthermore, they are also increasingly determining our lives. And with that, any error in their functioning could be tantamount to a catastrophe. Step by step, we are literally going to leave our lives to AI and robots – from Amazon shopping for shoes to getting directions in our cars, to judgment day – the use of AI in the judiciary and policing.

To achieve a sensible application of AI, AI programmers are inspired by nature. Animals – and even more so humans – are brilliant at adapting to change. This ability occurred because of a million-year long evolution. Reacting to changes in our environment – as a standard rule – increases the chances of animals and human beings to survive and reproduce.

As a consequence, robot engineers often wonder if one could replicate this kind of natural selection inside an AI code. This, for which the hope is, would do two things: it might create a more generalizable form of intelligence; and it might also enable AI to establish something akin to self-awareness of its very own functions.

If it were possible to develop such a form of general machine intelligence (AGI), it would need to be flexible, adaptive, and fast – like human beings. Such an AI-guided robot would need to be just as good as any person, even when faced with stressful situations – or even better.

Yet, today’s machine learning is improving constantly with the goal of reacting to challenging circumstances. They include unpredictable situations with a seemingly endless range of options. AGI appears to be a feasible option. Some even believe that we can create robots with a consciousness.

This question of conscious AI – the C-word – isn’t just another research question. It is “the” question of all questions for AI. If AI programmers can create a machine that has a consciousness equal to that of humans, it will outshine everything else that they have done so far. Some even believe that such an AI machine could cure cancer – by itself!

This leads to the question, is the AI-operated robot supposed to become a human? One of the first difficulties in analyzing the C-word is that there is no agreement among AI people on what the consensus is. Commonly, one might like to think that,

- conscious reflects awareness, while,

- consciousness is the state of being aware.

The no real agreement problem exists not just around consciousness, but also with many other concepts such as freedom, meaning, human understanding, love, feelings, passion, and even in existence itself. Overall, we enter into areas commonly reserved for philosophers – not engineers. Today, AI has changed that, somewhat.

Meanwhile, there is something that can be called philosophy of artificial intelligence. And, of course, in the age of neoliberal universities, it did not take long to find a master’s degree in the philosophy of artificial intelligence. It even comes with a very sensible syllabus.

Non-philosophers may be quick to classify consciousness through the use of brain functions or metaphysical substances. This idea believes that objects are constituted by its substance and its properties borne by the substance but distinct from it. This carries connotations to what the philosopher Kant calls the thing-in-itself.

Yet many of these attempts remain rather unconvincing – that is, not Kant’s but the ideas of substance theories. Beyond the substance theory, there are widely used definitions of consciousness such as, for example, those called phenomenal consciousness.

Among the advocates of this is the philosopher Thomas Nagel. Nagel believes that there is, what he calls, a conscious organism. Yet, he also believes that one can ascertain whether such an organism has obtained the level of consciousness or not by asking this famous question, what is it like to be a bat? – by inference, what is it like to be an AI ChatBot?

For AI, this means having a robot that is aware of its body and can think about its future plans for itself. Yet, for many robotics engineers and computer scientists, it is not all that satisfying to go fishing in the murky waters of philosophy.

Some argue that, as long as robotics engineers do not bring the idea of consciousness along, one gets the feeling that intelligent machines are missing something.

Even in the early days of artificial intelligence research in 1955, human traits were targeted when a group of early AI scientists at Dartmouth asked, how machines could solve problems and improve themselves, in the way that it is reserved for humans.

They wanted to recreate advanced brain skills formulated as a computer program covering elements such as language, abstract thinking, and machine creativity. Such a computational program is what we today call AI. For many of these abilities, awareness, and consciousness – the C-word – remains to be of central importance.

Trying to represent the fuzzy C-word in reliable data and coded functions is extremely difficult, in particular, when even the famous ChatGPT creates some very elaborate nonsense, as Yejin Choi said recently.

Quite a few people like to argue that furnishing AI with the C-word is an impossible task. As a consequence, most robotics engineers tend to, as it is called, “go beyond philosophy” (read: ignore philosophy and, worse, moral philosophy). They develop their own – often rather problematic – definitions of the C-word.

Others believe that the C-word (consciousness) can simply be reduced to a certain process and that the more we find out about the brain, the concept of consciousness (a subjective experience) will become clearer. In that, AI engineers make a typical, but rather devastating switch: from the mind (consciousness) to the brain. Both are not the same.

Unfortunately, such assumptions are rather common and not only among robotics engineers and AI programmers. Meanwhile, philosophers like Daniel Dennett and Patricia Churchland, as well as neuroscientist Michael Graziano have put forward a number of functional theories on consciousness (e.g. attention schema theory, control theory, and social cognition theory).

AI people tend to dismiss the C-word by convincing themselves that AI has approached the concept of consciousness practically, soberly, and unromantically. This is done to bypass philosophy. As a consequence, they like to focus on a so-called practical criterion for defining consciousness. Worse, it limits (perhaps even eliminates) the issue of the C-word to the ability to put oneself in the future.

They also believe that the fundamental difference between AI or machine consciousness and human consciousness, the consciousness of an octopus and the consciousness of a rat, for example, is whether such a being can imagine himself in the future.

As a consequence, the C-word can be imagined as a mere continuum. At one end of this, there is an organism that has a sense of where it is in the world. This might be called primitive self-awareness.

At the other end, more intelligent organisms have the ability to imagine where one’s own body will be in the future. In addition, they are also able to imagine what could be at some distant day into the future.

This is the ability to anticipate what might happen in the future and how one fits into such a future. A good example is David Wallace-Wells’s suggestion about what will life be after global warming and what will be the role of human beings.

As a consequence of the rapid development of AI, AI engineers are confident that, at some point, AI machines will be able to understand what they are and what they – themselves – think.

To make it even more complicated, the idea of what others think also comes in. Much of this means that the current AI is something like following a simple cockroach model.

For the concept of a philosophy-free AI, all of this is very important. The advantage of this so-called functional theory of consciousness – a gross reduction of the C-word – lies in the fact that this allows technological progress – hence, advancing AI. Evil heretics however, might say that it is no more than unconscious technological progress – but a dangerous development.

Thomas Klikauer is the author of German Conspiracy Fantasies – out now on Amazon!