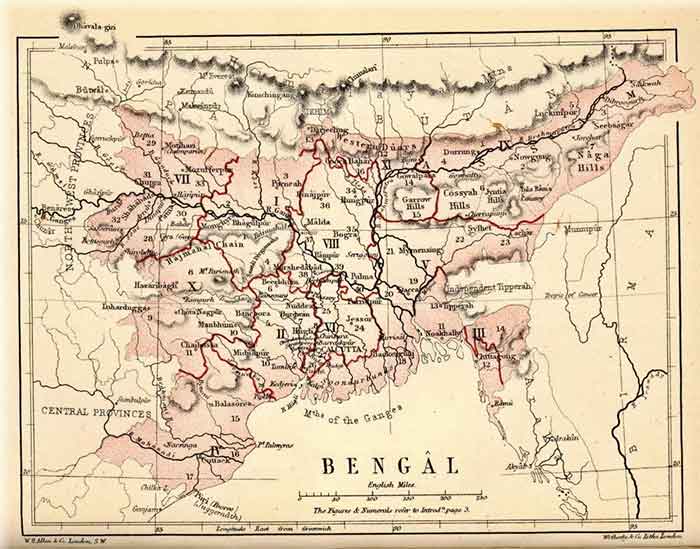

The area this article covers is this sub-continent’s partition and Bengal’s bifurcation. To be specific, it looks at a part of people’s journey forward in this land, which carries historic significance till today, although the area is hardly identified with its significance related to people’s journey toward liberation from bondages, and to social advancement. Struggle of the working people that they were carrying on that time is one of the least discussed areas related to the subcontinent’s segmentation, although the partition of the land and the bifurcation of Bengal impacted the struggle for emancipation gravely, with historical significance.

Three incidents are cited as symbols of the partition. These are like stories; but, these are real-life incidents; two from members of the people, and the third one is from one of the authorities.

Ms Madhu Bhaduri, a former ambassador in the Indian Foreign Service, was born in Lahore in a November-day in 1943. She, as she writes in Lived Stories, was “about three-and-a-half-years old when the city was set in flames, shortly before the partition.” She, her elder sister, her father, her family members “saw flames of fire rising” all around the city. The family members had to move to Delhi. But, her “grandparents and great-grandfather refused to leave their beloved Lahore, as to them, the city was their ‘home’.” Her “father’s grandfather died in Lahore on the intervening night of 14-15 August 1947, and had to be cremated within the house” at Racecourse Road. On the night, “when Pakistan and India were celebrating their respective independence, […] [t]he situation in the city was such that [the elder man] had to be cremated in the garden of the house. Some of the wooden doors of the house were used for the funeral pyre.”

The second incident is from the east. While riot was raging around, a saber wielding mob was fuming with hate and assaulting attitude, a mid-aged person in front of his home in Kolkata was trying to pacify the mob as he was telling them: “Please, don’t engage with killing. We are living here for generations, since our forefathers, we all, Hindus and Muslims, live here like brothers.” The narrator, Ahmedi Begum, was talking about her father, Ahmed Hossain, and that was a riot-day in 1946. The firsthand-description, published in Aneek, an independent socialist monthly from Kolkata, in its January-February 2023 number, added: It was unknown whether the rioters would have heeded to the plea of the lone man standing in front of the mob. But, the goaalaa, milkman, who supplied milk daily to Hossain’s family, told: “Daadaa, brother, what are you doing? Come with me.” The milkman, pulled Hossain to his home, away from the rioters, and hid him there in the milkman’s home while riot was raging around. It was near Bidon Street. At the same time, Ahmedi and other female members of the family were passed from their home’s rooftop to the adjacent home of Kalicharan, friend of Hossain. Female members of Kalicharan’s family put seedoor, vermillion, on forehead of the sheltered Muslim females, drew lines with aaltaa, and sheltered them in the prayer room. They were provided with food and water. Hossain and his family survived.

The third story is with Cyrill Radcliffe, told by Sunil Khilnani in The Idea of India. Radcliffe, the obedient servant of the British imperial interests, one of the personifications of imperial conspiracy, wrote to his stepson on August 14, 1947: “Nobody in India will love me for the award about the Punjab and Bengal and there will be roughly 80 million people with a grievance who will begin looking for me. I do not want them to find me.”

So, we find: love for land burns in a garden surrounded by flames of hatred, commoners’ fraternity defying sectarian dividing line, and admission of ill-trick that took toll – deaths, destitution and renewed sectarian conflicts yet to subside. The reality that emerged is a wallow of politics of the exploiting classes, triumph of sectarianism, and ground lost by the commoners.

Most of the mainstream discussions, now not few in number and not less in extent, on the issue – partition of the subcontinent – focus on a number of aspects:

[1] Role – who and which political party or force played what role; conspiracy, collaboration, capitulation, appeasement, inactivity, etc.

[2] Blame – who to blame, or who is/are responsible for the partition and sectarian violence.

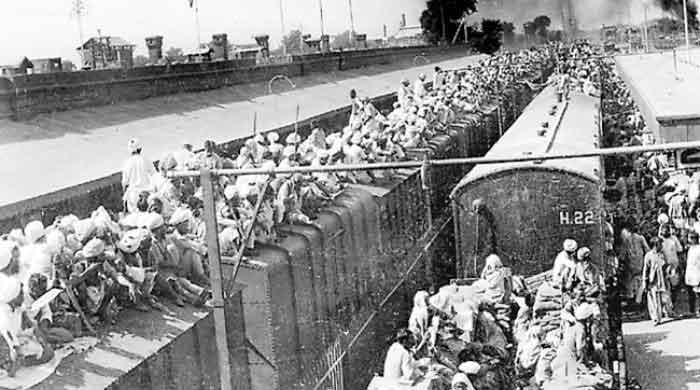

[3] Payment the people paid for politics of the exploiting interests – deaths, rapes, immiseration, loss of honor, painful migration. These include numbers, percentages, etc. – of death, migration, distribution and allocation of resources, literacy rate, economic activity including trade and industry, etc.

No doubt, the political tricks of the imperialist masters and its cohorts, alliances, compromises, actors in the dark part of political history of this land are to be discussed, dissected and identified, and presented before people. No doubt, the payment people made for the politics of the exploiting interests is to be told and retold vividly, in detail, so that the politics of the exploiters’ camp, and the camp’s nefarious tricks are exposed, so that awareness against dirty political game of the exploiters is spread among the people of this land, which help abort further dirty tricks of anti-people forces. The dirty tricks include spread of sectarianism among the people.

Along with the issues being discussed, focus should also be on the following:

[1] Class role – the role played by the classes present in the historical phase of the land: the exploiting classes and their master, and the exploited classes, as the roles show the capacity or incapacity of the classes involved or not involved in the politics, a political game by the ruling interests.

[2] Impact on classes – the political development impacted classes in the land, which had consequences on the class role(s) in further political development, which in turn negatively impacted the land’s historical journey to progress.

Even, interests secured and widened by a small section of the society, and rights of wider section curtailed/denied sometimes go unidentified in the mainstream discourse. That doesn’t help people know whether they gained or lost, whether they were served or betrayed. For the political awakening of people, this knowledge is essential.

Discussions on these – classes involved, etc. – issues or aspects help identify [1] class actors’ possible role in future journey towards advancement of society(ies); and [2] classes that can no more take lead, and classes that can and should take lead in respective society’s historical journey forward. Otherwise, politics of the classes connected to/dependent on imperialism, and their tricks would continue to prevail, all hope for betterment of life of the commoners will be banked on that old, retrogressive politics.

This article, therefore, takes a biased stand – biased towards interest of the people of this land, and tries to look at impact of the partition on the people’s journey.

Before entering into the issue, let’s have a brief look at the colonized subcontinent from the colonial masters’ view point.

[This is a modified part of a lecture delivered on an occasion organized by the Vivekananda Chair, Mahatma Gandhi University, India, on April 27, 2023, and based on an essay, “Class War in East Bengal, 1946 and Communist Party”, published in the Autumn Number, 2015 of Frontier, Kolkata.]