Last year, I had the opportunity to work with the youth from the indigenous/ tribal more aptly called the Adivasi communities in India in the Nilgiris Biosphere Reserve across the states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala in South India. In the months that followed, I was privileged to get a glimpse into their cultures, traditions and most importantly their sense of community and collective. It was a humbling experience and a journey that still throws up many learnings and moments of reflections when I consider my own sense of community or the lack of in a cosmopolitan city like Bangalore less than 300 kilometers away from the Nilgiris. But this article is not so much a narration on the differences between the two geographies and communities but a reflection on the relationships shared with the commons and the consequences of marginalization. I conclude the piece with my observation and perspectives from communities who have taken a decision to challenge the capitalist model and embody communitarian approaches as a way of life as potential solutions to the multitude of crisis we find ourselves in today.

My mornings usually start with walking my dog in the relatively quiet neighborhood on the outskirts of Bangalore city where I live and over the years have observed common spaces gradually shrink. The open space where women would graze their cattle and children from adjoining settlements played cricket are now taken over by private entities who put up fences or gates to limit the access of people. This is unlike my experience in the Nilgiris when the Adivasi youth took me to their villages to meet their families and friends. I did not see a fence, boundary wall or a gate, enclosing a natural resource like a forest, lake, mountain, or even an enclosure limiting people’s access to each other and the natural abundance around them. The fence as we know is not merely a boundary for safety and security but needs to be understood in the historical context as an enclosure of the commons on which stands the capitalist system. It allowed the ruling classes to control resources thereby displacing peasants from their land who sought work as wage laborers in enclosed estates in mid 14th century Europe (Federici.S, 2004). This is better understood in the work of Silvia Federici in her book Caliban and the Witch (2004) where she highlights the enclosure of the commons and the persecution of women as witches as intertwined phenomena that shaped the development of capitalism. The persecution of women as witches was not only a form of gendered violence but also a means to control women’s reproductive labor and knowledge of herbal medicine and contraception, which threatened the emerging capitalist order, further highlighting the intersections between gendered violence and the exploitation of human and natural resources (Federici.S, 2004)

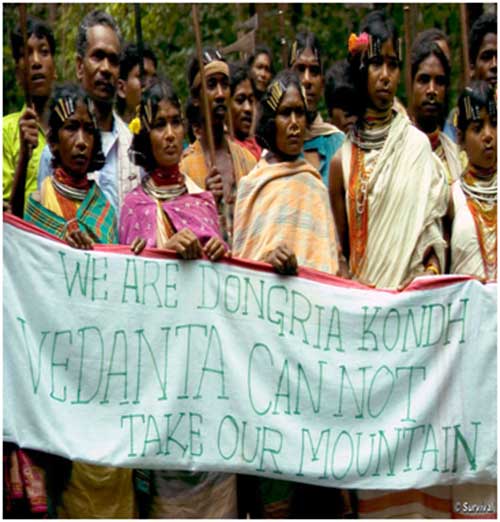

The tossing out of the fence and realization of the true potential of the commons as practiced by several communities across the world like the Adivasis in Nilgiris India is a powerful alternative to challenge the modernist view of universalism and the exploitative and extractive system of capitalism. In this regard it is important to understand the commons as a social system of three basic interconnected elements: 1) a commonwealth, that is, a set of resources held in common and governed by 2) a community of commoners who also 3) engage in the praxis of commoning, or doing in common, which reproduces their lives in common and that of their commonwealth (Angelis.M, 2019). The tripartite relationship between the commons, commoners and commoning is a critical approach to ensure that commons are seen as sites of social reproduction that are equally accessed by all as opposed to just being common goods that are collectively owned and managed. Social relations continuously produce commons which need to be constantly renewed and reproduced. The production of commons also constantly reasserts the validity of the ties of cooperation, reciprocity and the continuous process of producing and reproducing life. This reproduction of life which is nurtured, protected and adapted within various communitarian weavings resist and defend themselves from the aggressions of capitalist accumulation and encourage the expansion of creation which capital cannot overcome ((Aguilar R.G, Linsalata, Trujillo, M.L.N, 2016). One of the tribes that I worked with in the Nilgiris is a good example of this approach to the commons, the Kattunayakan tribes who traditionally gather honey from the forests, leave a share of the honeycomb for the bears to feast. They retain a small share of it for their families, and the third share is for the consumers through a social enterprise “The Third Share.” This is an alternative trade and marketing system by establishing direct links between like-minded communities that enable them to directly trade with each other and thus build a robust network of local economies that works for the mutual benefit of all its members and is controlled by the Adivasi communities.

Unlike the Kattunayakans in the Nilgiris the approach to lake commons in my city Bangalore is through the lens of bourgeois environmentalist that has led to the exclusion of lower income communities whose food and water security, cultural and spiritual needs depend on these lakes. Instead now they fulfil urban recreational and leisure needs such as jogging, walking and cycling tracks, bird watching zones, and so on and considered an oasis of nature in the city (Rao.M, 2020). The commons approach as epitomised by the work of Federici, De Angelis and practiced in the Kattunayakan Adivasi community in the Nilgiris is noteworthy but it leads to oppression and marginalisation of the community unlike the approach outlined for lakes in Bangalore. And this marginalisation is gendered as the everyday processes of communing are mostly done by women through sharing and caring and it is women whose everyday lives depend on the commons (Federici.S, 2019). The constant social reproduction caused by the amalgamation of the commons, commoners and communing builds the communitarian weaving resisting the oppressive attempts by capital. The physical self, embodying this resistance and healing multiple forms of alienation is crucial to address the social, political and ecological crisis of our time rooted in trauma caused by capitalism, colonisation and patriarchy.

Neha Saigal Works at the intersections of gender and climate change and is a student of political ecology and degrowth.