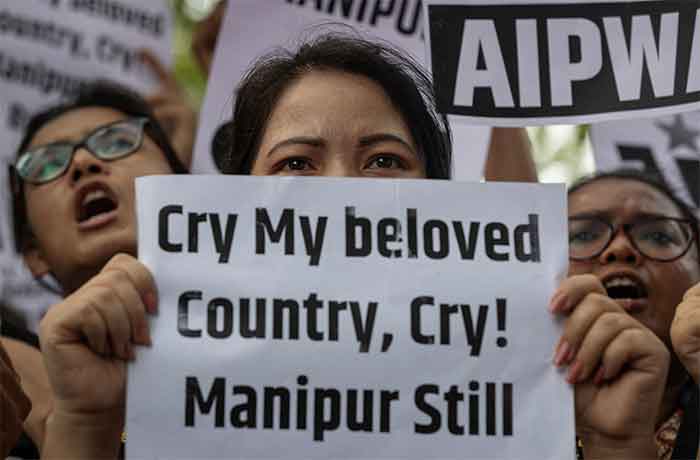

`A woman, spreading a sack before her like a fish stall/ Sells bodies of little children /Dead from gunshot wounds/

Sprinkling water and rubbing the corpses/ She says laughing carelessly: “Not anyone’s/ Not anyone’s children, mind you/

These children are my own.” ( Thangjam Ibopishak, Manipuri poet who composed this poem some twenty years ago.

Quoted in `Where the Sun Rises When Shadows Fall – The North-east’ in India International Centre Quarterly, Monsoon-Winter, 2005 )

When reading the daily reports of the ongoing ethnic strife and killings in Manipur , I keep remembering the old history of the state, and my personal experiences there during my occasional visits to Imphal and Ukhrul . At the same time, looking back at those impressions, I now realize how incomplete they were. They were confined to the valley of Imphal, mainly among my Meitei friends, and to Ukhrul where I had a few Naga friends. The Kukis of the hills were totally out of our perception. We ignored signs of a divisive disaster that was waiting to happen.

To start with, in the past, Manipur (known as Kangleipak) was ruled by small chieftains and their various clans, who later merged to form the Meitei community which lived in the plains, while those living in the hills followed their tribal tradition of animist beliefs and came to be known as `Hao.’ It was in the 15th century that the land-locked country was exposed to external influences when Hindu Brahmin priests from the mainland India migrated to Manipur to expand their religious empire by converting the Manipuris. Many Meities converted to Hinduism. But the country still remained a melting pot of different cultural and religious streams, as evident from the Manipur rulers allowing Muslims to settle down there in the early 17th century. They were known as Meitei Pangals (whose descendants are still there). (Re: Yumnum Oken Singh and Gyanabati Khuraijam – `The Advent of Vaishnavism: A Turning Point in Manipuri Culture’, published in European Academic Research, Vol. 1, Issue 9, December 2013).

The Bengali connection

It was many years later, in the 18th century that Hinduism, in the shape of Vaishnavism actually got a firm foothold in Manipur – and that also thanks to a Bengali priest. By then the Manipur royalty had been veering towards Vaishnavism, with its king Chara Rongba converting to it, under the influence of the proselytizer Nimbarka who visited Manipur in 1704. Some years later, Garibniwaz (known as Pamheiba in Manipuri) became the king, who turned out to be a fanatical devotee of Vaishnavism, under the influence of the royal priest. This priest happened to be a Bengali Vaishnavite called Shantidas Goswamy who migrated from his homeland in neighbouring Sylhet, and managed to gain the king’s confidence. Such was his power of proselytizing that he could persuade Garibniwaz to destroy the traditional Meitei temples and idols of local deities. The old Manipuri script was gradually eradicated to be replaced by the Bengali script. But in the midst of these destructive trends brought about by the Bengali Vaishnavite influence, there was one positive effect in the cultural sphere. The Vaishnavite legend of the Radha- Krishna romance was introduced in the form of the Raas Leela dance, which was soon adopted by the Manipuri performers. But they gave it a distinct form by shaping it according to their traditional dancing style. This development led to the emergence of a unique genre of dancing , known as Manipuuri dance in the world arena of choreography .

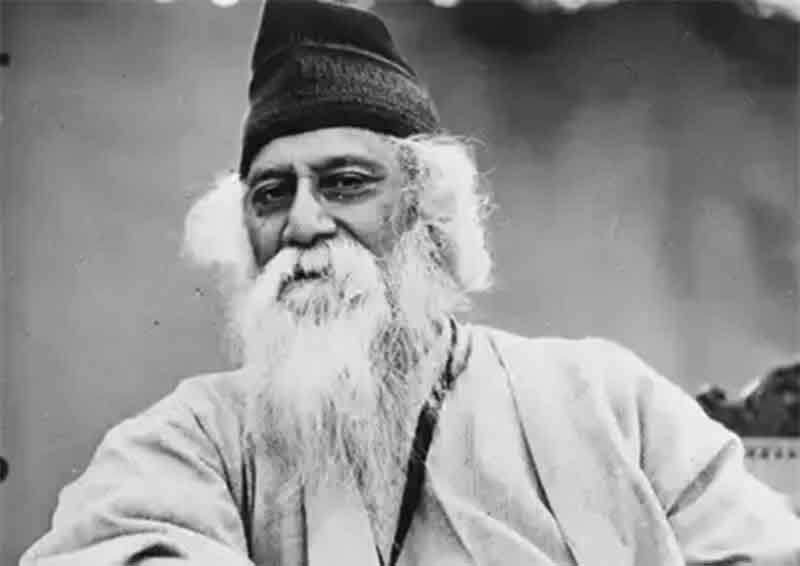

Again, the expansion of the Manipuri Raas Leela style of dancing beyond the borders of Manipur was also made possible by another Bengali. Rabindranath Tagore had been fascinated with Manipur since his youth. As early as 1892, he composed a dance drama called `Chitrangada,’ based on the mythological story of Arjuna falling in love with princess Chitrangada of Manipur in north-east India, as narrated in the Mahabharata. In 1919, Tagore had a chance of watching an actual Manipuri dance performance at a public function in Sylhet (now in Bangladesh, neighbouring Manipur). Impressed by the dancing style, he invited the teacher of the dancers, Guru Budhimantra Singh to Shantiniketan. This was the time when Tagore was planning to set up an educational hub there, which was to become later the Vishva Bharati University. Guru Budhimantra Singh’s visit to Shantiniketan laid the foundation of a long history of Manipuri-Bengali cultural affinity. Once Vishva Bharati was established, an array of famous Manipuri dance teachers came there. Guru Naba Kumar, Senarik Singh Rajkumar, and Atomba Singh among others, assisted Tagore with the choreography of his dance dramas.

Arrival of a Manipuri princess in Shantiniketan in the 1940s

In the early 1940s, the then king of Manipur, Churachand Singh, sent his daughter, the young Binodini to the Vishva Bharati University in Shantiniketan. Here she entered Kala Bhavan (the department of arts) as a student of the famous sculptor and painter Ramkinkar Beij. Her apprenticeship under Ramkinkar not only turned her into a sculptress, but also turned her teacher into an ardent soul-mate of hers. For Ramkinkar, Binodini became a muse who inspired him to paint her in a series of portraits – which are preserved in the Kala Bhavan archives.

After her stint as a student in Kala Bhavan, she returned to her ancestral royal home in Manipur. Here in 1950, she married and settled down as a home maker. But Binodini was brimming with new ideas that she had imbibed from her brief stay in Shantiniketan. Although she could no longer pursue her sculpting and painting activities due to household obligations, she turned her talents to writing short stories and lyrics in Manipuri. Soon she established herself as a reputed writer, known as Maharaj Kumari Binodini in literary circles and came to be popular among the common Manipuris as `Imasi.’ Two films were made on her by the famous Manipuri film maker Ariban Shyam Sharma.

But beyond her literary achievements, there was another side to this Manipuri princess. While growing up as a young girl in Manipur, she had been inspired by the political ideas of her cousin, Hijam Irabat Singh (1896-1951), who although belonging to the royal family, chose to become a Communist and protest against the injustice meted out to the oppressed poor. Till the end of her life, Binodini retained this spirit of protest that she imbibed from her cousin. In 2004, she returned the Padma Shri award in protest against the rape and killing of a Manipuri woman, Manorama Devi by the Indian para-military Assam Rifles.

Long before this, I happened to briefly meet MK Binodini in Imphal sometime in the early 1960s, when I was assigned by my newspaper The Statesman to cover some event there. In the course of my reporting, I ran into the film maker Ariban Shyam Sharma, who was then making a film on Binodini. One day, he took me to Binodini’s home. She was in her forties, but her face still reminded me of the youthful beauty and charm, that were captured some two decades ago by Ramkinkar in his paintings. We had a long chat – she recounting her memories of her teacher Ramkinkar in Shantiniketan, and I replying to her queries about the current state of affairs in her former beloved campus.

Manipur’s radical tradition of protest – and its degeneration into ethnic conflict

When I was growing up as a Leftist student activist in Calcutta (now renamed Kolkata) in the 1950s, I along with my comrades, was inspired by the revolutionary activities of the legendary Manipuri Communist revolutionary, Hijam Irabat Singh – who as I came to know later was related to MK Binodini. Irabat was a social reformer, poet and revolutionary, all rolled in one. He joined the Communist Party in the 1940s, and was jailed from 1943-44. After his release, he resumed his association with the party. Post-Independence, in 1948 he formed an underground Communist Party in Manipur, and organized armed struggle against the Indian government, accusing it of suppressing popular aspirations of Manipur.

Since then, the radical movement in Manipur had undergone changes, with several armed groups operating in the valley. The oldest among them is the United National Liberation Front (UNLF) founded in 1964 with the aim to establish a sovereign, socialist Manipur. This was followed by the establishment of the People’s Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak (PREPAK) in 1977, with the goal of ousting outsiders from the state, and restoring the old Meitei script. The next was the Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) which was founded in 1978 with the objective of setting up a separate socialist state of Manipur. Then there is the Kangleipek Communist Party, a Maoist group that was formed in 1980, which is again split into several factions now. The Maoist Communist Party of Manipur emerged in the late 2011, with its armed wing New People’s Militia. Significantly enough, all these Leftist groups are Meiteis, and primarily concerned about the preservation of their Meitei identity, demanding secession from the Indian state. Today, in the current ethnic warfare in Manipur, they are indistinguishable from the Meitei chauvinist terrorist groups like `Meitei Leepun,’ and `Arambai Tenggol.’ The Imphal valley based Communist groups never reached out to the Kuki and other tribal people living in the surrounding hills.

Yet, the Kukis also faced problems in their interaction with the Indian state, as the Meteis and Nagas. The accession of the princely state of Manipur to the Indian Union, which was later made into a full-fledged state in 1972, was perceived by all these inhabitants as a threat to the autonomy that they had been enjoying. This gave rise to various anti- Indian insurgent movements by different sections. As described above, the Meiteis living in the valley, formed their armed groups. Similarly, the Nagas and Kukis living in the hills set up their own guerilla squads to fight the Indian army. But these insurgent groups failed to get together and put up a united front. Instead, they fought among themselves along ethnic divisions. The worst example of such conflicts was the massacre of more than 100 Kukis by Naga militants of the Nationalist Socialist Council of Nagaland (Isak-Muivah) – known as NSCN(IM) – on September 13, 1993. The Kukis formed their own groups – Kuki National Organization (KNO) and its military wing Kuki National Army (KNA) to resist such onslaughts.

Roots of the triangular Meitei – Kuki – Naga conflict giving birth to the murky murderous politics of Manipur

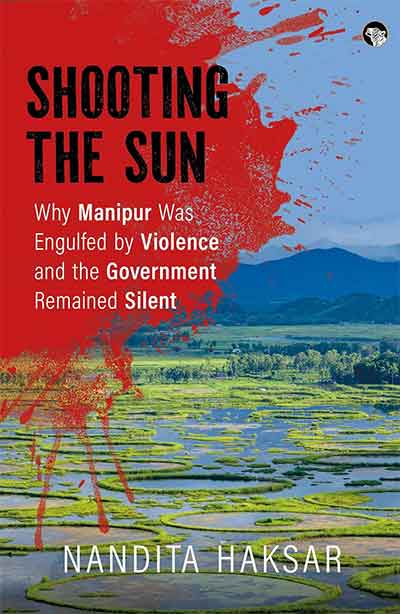

For an interesting analysis of the socio-cultural origins of the present conflict, one should listen to the reminiscences of Thuingaleng Muivah, the well-known leader of the NSCN(IM). In the course of several interviews carried out by two human rights activists, Nandita Haksar and Sebastian M. Hongray during 1998 and 1999, Muivah revealed the complicated triangular relationship that he witnessed while growing up as a .child and later in his youth, as a Naga in Ukhrul, the Naga dominated district in the hills of Manipur. He grew up with his mother telling him stories about how Kukis raided her village, killed the Nagas and forced her family into hiding. But at the same time, the Naga tribal society was also divided along sub-tribal lines. The Tangkhul community of Nagas was looked down upon by the Ukhrul Nagas. Muivah belonging to the Tanghkhul community, suffered humiliation at the hands of the Ukhrul Nagas who used derogatory terms for him. As for interaction with Meiteis, Muivah said: “The Meiteis would not allow Tangkhuls to enter their homes, especially their kitchens. We were allowed to sit or sleep on mats on the verandah.” He acknowledged that the “Communist Party did a lot to change things,” but added that it “did not take strong roots in society.” Recalling the role of the revolutionary Communist Irabat Singh, he said that Singh “had no influence in the hills and the Nagas were not attracted to the Communist Party of India.” Coming to the present times, Muivah talked about the main insurgent groups, UNLF, PLA and PREPAK (all Meitei and valley based), and complained: “…they also treat hill people with disdain.” (Re: KUKNALIM: Naga Armed Resistance. Testimonies of Leaders, Pastors, Healers and Soldiers. Compiled by Nandita Haksar and Sebastian M. Hongray. New Delhi. 2019).

This triangular ethnic conflict assumed political dimensions over the years – differing from one community to another. For the Meities, it assumed an anti-Congress stance. In 2004, during the Congress regime, a Meitei woman Manorama was raped and killed by soldiers of the Assam Rifles who were deployed there to suppress insurgency. It led to a demonstration of Meitei women who stripped themselves in front of the Assam Rifles headquarters, shouting “Indian Army, rape us !” Soon after that, a Meitei woman, Irom Sharmila started a fast unto death in protest against the Armed Forces Special Act, the draconian law that had given immunity to those Assam Rifles personnel against prosecution for their raping and killing of Manorama. Arrested and confined in police custody, Irom Sharmila was forcibly fed by her jailors to keep her alive, but she deliberately continued to suffer this physical torture for almost sixteen years, just to highlight the plight of her community under an insensitive Centre.

After the BJP came to power at the Centre in 2014, Narendra Modi tried to reverse the earlier Congress government’s stance by wooing the Meiteis. On the eve of the 2017 Assembly elections, in a cunning manouevre, it cajoled both the Hindu Meiteis in the valley (who in any case leaned towards the BJP due to their religious affinity) and the Kuki tribes in the hills to vote in favour of its candidates. Two BJP leaders – Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma and Ram Madhav who were deputed by the party’s central leadership to look after Manipur – approached Kuki militant outfits for support. In exchange for their support, these Kuki groups demanded that the BJP, if voted to power, would respect the tripartite Suspension of Operation (SoO) agreement that was signed in 2005 by the Government of India, the state government of Manipur, and two militant groups, Kuki National Army and Zomi Revolutionary Army. This ensured a cease fire in the troubled state of Manipur. The BJP leaders promised to adhere to the SoO, and in response, the Kukis voted for two BJP candidates, helping them to win. (Re: Letter addressed to Union Home Minister Amit Shah in 2019, in an affidavit submitted to the NIA court by S. Haokip, chairman of United Kuki Liberation Front). This is how the BJP managed to win the election and form a government with N. Biren Singh as its chief minister in 2017. Five years later also, in 2022 he bounced back to power – again with the support from the Kuki groups.

But this time, during his second term, he went back on the promise made to the Kukis. Firmly saddled in his seat in Imphal with overwhelming Meitei support, and fully backed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi from the Centre, he felt that he could dispense with Kuki support. The sequence of events in March this year points out at his new policy. On March 10, 2023, he cancelled the SoO agreement of 2005, thus renewing military operations against the Kuki militant groups which had remained dormant during the last two decades. One suspects that he was preparing for an onslaught on the Kukis, as evident from his government’s issuance of gun licenses (mainly to the Meities) – reaching the highest number in the north-east. (Re: The Wire, July 12, 2023). This suspicion is reinforced by the widely publicized report of his administration remaining a silent spectator to Meitei crowds invading police stations, capturing weapons and escaping without any obstruction, on the eve of the present outbreak of violence. On March 24, 2023, Biren Singh announced the withdrawal of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act from several areas of Manipur – a decision which reinforced his popularity among the Meiteis who had been fighting against that draconian law for years. Soon after, on March 27, 2023, the acting chief justice of the Manipur High Court, M.V. Muralidharan delivered a judgment directing the state government to recommend the inclusion of the Meitei community in the Scheduled Tribes (ST) list. It took the Supreme Court two more months to declare that Muralidharan’s judgment was wrong – a delay that cost a lot, and also showed up the slow judicial process even at the apex court. On May 17, Supreme Court Chief Justice Chandrachund dismissed Muralidharan’s judgment as “absolutely wrong,” on the ground that state governments did not have the power to take such a decision. But by then damage had already been done. Muralidharan’s judgment had sparked fears among the Kuki tribals, who apprehended that once the Meities were given the ST status, they would have free access to their territory in the hills and grab their lands. On May 3 the All Tribal Students Union held a march protesting against the erroneous judgment, which ended up with clashes between the Kukis and Meiteis – which still continue.

The clashes have taken on a communal character with reports of state-supported Hindu Meitei militant groups targeting the Christian Kukis and burning their churches. They have been described as “State-sponsored’’ by Ms. Annie Raja, who visited Manipur as a part of a three-member fact-finding team in July. These ongoing incidents, exposing the failure of both the Centre and the Manipur state government to stem them, have reached such an extent as to draw the attention of the European Parliament (representing the West European nations) which on July 13, adopted a resolution calling on the Indian government to act “promptly” to halt the violence in Manipur, and protect religious minorities.

The secret story behind the tussle over the hill districts of Manipur

But behind this recent outbreak of ethnic conflict between the Meiteis of the valley and Kukis of the hills, there hovers a dark commercial deal that was signed by the Biren Singh BJP led government with several mining companies soon after he came to power in 2017. What is little known and seldom highlighted by the mainstream media is the fact that the hill districts of Manipur contain rich deposits of chromite, limestones, nickel, copper and various platinum group of elements (PGE) which are of immense value for multinational manufacturing industries. In order to attract them, Biren Singh organized a two-day meeting in Imphal in November 21-22, 2017, known as the North East Business Summit, where his government signed a number of MoUs with several mining companies, which transferred to them land and giving them mining rights in the hill areas of Ukhrul, Chandel, and Churandchpur among other places. These areas are inhabited by the Tanghkul Naga and Kuki tribal people. (Re: Jiten Yumnan: `Nuances of Mining plan in Manipur’ in The Sangai Express, August 25, 2020). They naturally felt threatened by the possible encroachment on their lands by these mining companies which had been entitled to such occupation for mining purposes. They soon started organizing themselves to protest against Biren Singh’s deal. On August 4, 2020, the Youths Action Committee for Protection of Indigenous People, appealed to the Government of India, the government of Manipur and multi-national companies, to immediately stop the extraction of limestones, chromite, and other mineral resources, as such mining threatened the livelihood of the indigenous people. The Kuki demonstrations from the hills therefore should not be viewed as manifestations of sheer ethnic self-assertion, but also as protests against the encroachment on their lands by the mining companies that threaten their livelihoods.

Sumanta Banerjee is a political commentator and writer, is the author of In The Wake of Naxalbari’ (1980 and 2008); The Parlour and the Streets: Elite and Popular Culture in Nineteenth Century Calcutta (1989) and ‘Memoirs of Roads: Calcutta from Colonial Urbanization to Global Modernization.’ (2016).