In March, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, said at an election rally in Arunachal Pradesh that previous governments had not cared for states that sent only two representatives to the country’s Parliament, as Arunachal and several others in the Indian Northeast do. Modi failed to see the irony of his claim given that he has not visited Manipur, which has only two representatives in parliament, since the outbreak of an armed ethnic conflict that has raged on for nearly a year. The toll from the violence stands at more than 200 lives lost, and many thousands displaced.

In India’s 2024 national election, widely seen as being decisive for the country’s democracy, the eight states in the Northeast—Assam, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura, and Meghalaya—will decide whether they want to be part of “Modi ka parivar,” or Modi’s “family”—a phrase that Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has rolled out on social media as an election gambit. The BJP-led central government in Delhi has repeatedly claimed to have bridged the “tyranny of distance” between the Northeast and the rest of India, something that the region has undoubtedly long suffered from. Unfortunately, the Modi government’s handling of the Manipur crisis shows otherwise—and none of the BJP’s numerous political partners in the Northeast region, who often profess themselves to be “sons of the soil,” have challenged the government’s claim.

The Northeastern states combined send only 25 representatives to the Lok Sabha, the 543-seat lower house of the Indian parliament. Assam, the most populous of the states, accounts for 14 of these alone. The perceived remoteness of these states, connected to the rest of India by only a narrow “chicken’s neck” of a corridor in West Bengal, is another factor that has kept the region on the fringes of national politics. What’s more, the Northeastern states are among the country’s poorest—with the exception of Sikkim, which has the highest per-capita net domestic product of any Indian state—and among those most heavily dependent on central funds. In fact, the central government has a ministry dedicated to the development of the Northeast, going by the acronym DoNER, which channels 10 percent of the annual budgets of all 52 central ministries to infrastructure projects in the region. Regional experts often remark that the Northeast is compelled to follow Delhi’s lead because of this historical dependence on the center.

The BJP secured its first electoral victory in the Northeast when it won an assembly election in Assam in 2016. Since then, it has gained a hold over much of the region and worked to better integrate it with the rest of India. But the specifics of that integration follow a very particular vision: for the BJP, the Northeast is not beyond the purview of its longed-for Hindu Rashtra, or Hindu nation. In a region long perceived to be dominated by Christian groups, the party has played on the sentiments of the Northeast’s Hindus, who constitute a 53-percent majority in the region cutting across multiple divisions of language, ethnicity, and caste. With this approach, the last decade of BJP politics in the Northeast has exacerbated internal divisions in a region that was already struggling with bloody schisms to begin with. The Manipur conflict is one symptom of this.

In the early 2000s, even while Atal Behari Vajpayee headed a BJP-led government at the center, the opposition Indian National Congress was in power in four of the Northeastern states, and in ruling coalitions with regional parties in two others. Once the Congress returned to national power, the grand old party’s presence and power in the Northeast remained more or less a constant. That was until 2014, and Modi’s ascent to prime minister. Like almost everywhere else, the BJP has used money and power to completely change this electoral picture in the Northeast, throwing large sums into campaigning in this region where many voters openly accept bribes. The party also played mitra, or ally, to various regional parties, and partnered with them in numerous state governments.

Unlike the Congress, which typically chose to take on electoral contests in the Northeast alone, the BJP entered the region relatively quietly through alliances with the National People’s Party in Meghalaya, the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) in Assam, the National Democratic People’s Party in Nagaland and the Indigenous People’s Front of Tripura. In a region with a dizzying mix of ethnicities and cultures, not only did this help deflect attention from the BJP’s general reputation of being anti-minority, or being against anyone who was non-Hindi or not caste Hindu, but it also enabled the party to poach certain regional leaders. For example, Sarbananda Sonowal, the former chief minister of Assam and leader of the AGP, joined the BJP in 2011. The AGP eventually declined and is now reduced to being a token partner in Assam’s BJP-led five-party coalition government. Such poaching by the BJP effectively ended the political runs of several regional parties. Helped by this, since 2014 the BJP has gone from a bit player to a dominant force in the politics of the Northeast, forming state governments in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, and Tripura.

Moreover, the BJP has been able to exploit historical resentment against the Congress, which presided over the many brutalities of the peak years of insurgency in the Northeast, in the 1980s and 1990s. After a dark phase of counterterrorist operations and extrajudicial killings that lasted into the early 2000s, Assam saw relative peace under a Congress government at the center from 2004 onwards. Yet the BJP has successfully blamed the Congress for allegedly encouraging illegal immigration into the Northeast, primarily from neighboring Bangladesh, by “appeasing Muslims.” The BJP has even interpreted a radio speech by the Congress icon and former prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru as reflecting the rival party’s indifference to the Northeast. Speaking in 1962, when China invaded India, Nehru used the phrase, “My heart goes out to the people of Assam at this hour.” His political opponents have long claimed that this was a signal that Nehru had abandoned Assam to its fate—an accusation that the BJP has continued to drum up in its 2024 electoral campaign.

The BJP has temporarily neutralized civil society groups and armed groups in the region that would, in earlier times, have likely stood in opposition to the central government. The home minister, Amit Shah, boasted during the election campaign that the Modi government has signed nine peace accords in the Northeast in the last 10 years. Given that the Northeast has long had the greatest concentration of secessionist groups and movements anywhere in India, the first order of business for any government looking to impose itself on the region is to establish peace, preferably through political settlement. However, the Modi government’s peace agreements look better on paper than on the ground.

For example, the government’s first major move in the Northeast after coming to power in 2014 was to sign a framework agreement for a Naga peace accord with the Isak Muivah faction of the Nationalist Socialist Council of Nagalim (NSCN-IM). Given the Nagas’ history of demanding self-determination and standing against union with the rest of India, a firm agreement with the Naga leadership for a settlement within the Indian republic would have been a landmark achievement.

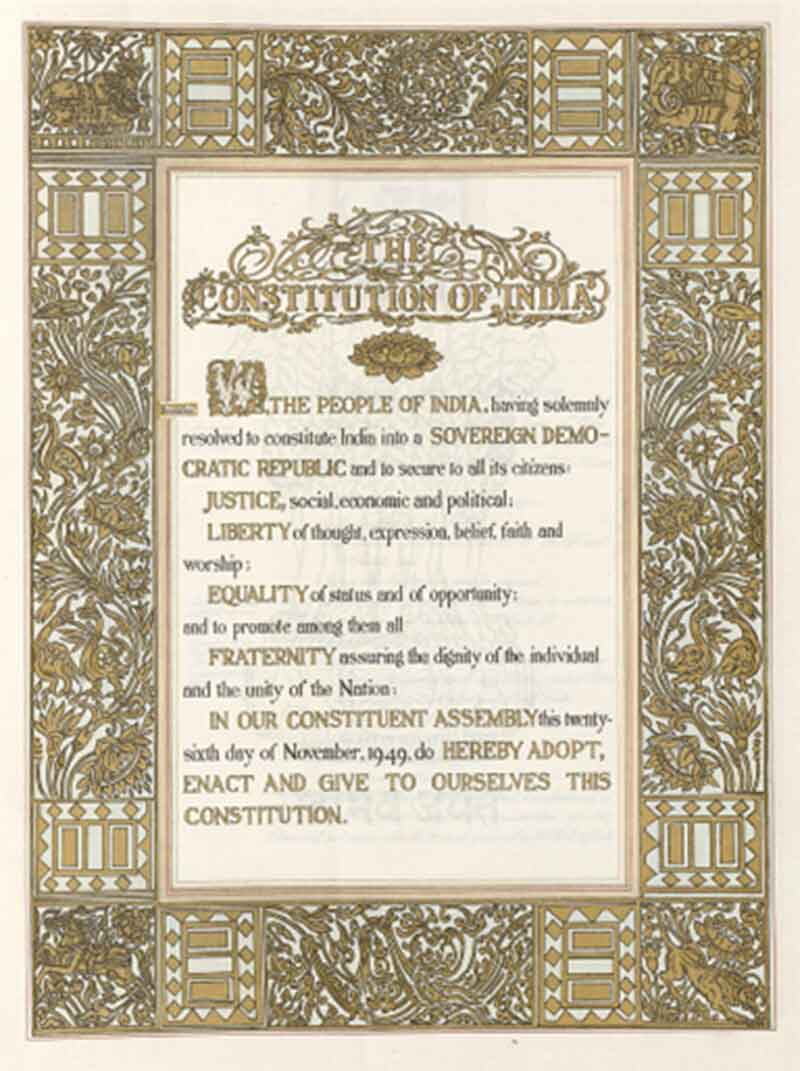

However, the framework agreement was ambiguous in ways that eventually left the Nagas feeling let down. Naga negotiators had agreed to share sovereignty with India while retaining Naga’s unique identity, as well as a separate flag and constitution. However, after the Modi government unilaterally abrogated Article 370 of the Constitution of India, which allowed for special constitutional status and autonomy for the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir, it became clear that the BJP government was pursuing a policy of “One nation, one constitution.” The Nagas were blindsided and talks went into a stalemate.

Then there is the example of the Bodos. The Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution offers special privileges regarding land and resources to groups recognized as Scheduled Tribes (a government-recognized disadvantaged socio-economic group in India.) After a bloody struggle, the Bodoland Territorial Council emerged in 2003 out of a settlement between the Bodoland Liberation Tiger Force and the governments of India and Assam. Such territorial councils, under the provisions of the Sixth Schedule, empower a designated tribal community in a designated region to self-govern within constitutional limits, with earmarked funds from the central government. Despite claims that the BJP has fulfilled promises of the accord such as providing direct funding to the Bodo Territorial Council, the Indian government has categorically said that it has not. Meanwhile, even as Bodos have continued to engage with the government, their claims and ambitions have been pushed back. Under an agreement signed with the Modi government, the Bodo leadership’s purview extends only over a “region,” and not over a full-fledged state as the Bodos once hoped for.

More recently, the government has signed agreements with factions of the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA) and the United National Liberation Front (UNLF) of Manipur—two insurgent groups known to be among the least amenable to negotiations. ULFA was founded in 1979 with the professed aim of liberating Assam from exploitation by India. The UNLF, established in 1964, has been advocating for Manipur’s secession on the basis that its former ruler should never have agreed to merge with India in 1949.

The Modi government brandishes its agreements with these two old and formidable militant groups as impressive achievements, but they were, in fact, low-hanging fruit. Support for ULFA in Assam has decreased considerably in the last decade, with a steady fall in recruitment, partly due to fatigue with the group’s Ahom revivalist mission and partly due to backlash after a series of blasts linked to it that killed civilians. The government signed an agreement with a pro-talks faction of ULFA in 2023, while an anti-talks faction refused to abandon the armed movement unless the government was willing to discuss sovereignty for Assam. The fact that the agreement led to the disbanding of the pro-talks faction while the more militant anti-talks faction continues to survive has left a major, and potentially dangerous, loose end.

In Manipur, the government was all set to sign an accord with the Kukis in May 2023—much to the displeasure of Biren Singh, the BJP leader and chief minister of Manipur, according to a report in the Wire. Singh belongs to the Meitei community concentrated in the Imphal Valley, which has long been at odds with the Kuki Zo tribes of the surrounding hill districts of Manipur. Kuki Zo communities, who complain of disadvantage and discrimination under the Meiteis’ established dominance of Manipur politics, have been asking for separate statehood since the 1980s. The accord would allegedly have granted them autonomy under a territorial council. However, the violence in Manipur broke out the very month the accord was to be signed, pitting the Kuki Zo tribes against the Meiteis, and there has been no movement on it ever since.

Instead, there is increasing doubt that the ceasefire agreement between Kuki insurgent groups and the central and state governments, first signed in 2008, will be extended. Far from bringing real peace to the hills or the Imphal Valley in Manipur—the Modi administration has faced widespread criticism for not stemming the violence—the central government has signed a cosmetic peace agreement with the pro-talks Pambei faction of the UNLF, even though it has refused to surrender its arms. Instead, members of this armed group have openly carried AK-47, M-16, and INSAS rifles, which are among the more than 5,000 weapons stolen from government armories, and are carrying out military-style operations aided by drone surveillance to attack Kuki villages in the hills. The armed faction has often fought along with Manipur police commandos, with the central security forces functioning as nothing more than mute spectators.

The extortion of civilians by armed groups, something commonplace in earlier years, saw a brief lull in the initial years of BJP rule. Now, with armed groups resurgent across Manipur amid the conflict, the phenomenon has returned to both the hills and the valley. And the tensions in Manipur have naturally overflowed into neighboring states. The NSCN-IM has already warned the government against settling the Pambei faction in the Naga hills. As the Kuki Zo tribes and Meiteis fought each other in Manipur, many Meiteis in Mizoram were forced to leave the state after open threats against them by a local Mizo group.

Even the tripartite agreement signed in February between the Modi government, the Tripura state government, and the recently formed Tipra Motha party appears to cede political advantage only to the BJP. The Tipra Motha has seemingly compromised on its demand for a separate state for the indigenous Tiprasa people in exchange for a territorial council with more seats. Tripura’s chief minister, Manik Saha, who is from the BJP, has said that only Modi can ensure the development of the state’s tribal communities.

This has become a widely held belief among tribal communities across the Northeast. This explains why, in Manipur, Kuki Zo MLAs from the BJP and the Kuki People’s Alliance, one of the national party’s local partners, continue to be faithful to Modi’s party even after being driven out of the valley and shut out from assembly proceedings.

Much of the mainstream media across India has failed to look at the fine print of the peace agreements. Instead, it has followed the official line of hailing them as victories for the ruling government, alongside touting statistics like an 86-percent reduction in civilian deaths across the Northeast since Modi’s arrival in power. What such coverage has ignored is the wider atmosphere of conflict and heightened insecurities within the region, and the distrust that the one-sided “peace agreements” have engendered in the people of the Northeast, who have seen their long-standing demands being traded away cheaply.

The BJP model of governance to pacify tribal minorities caters to a political status quo that favors ethnic majorities in specific regions, and this has further cemented feelings of “us versus them” between ethnic communities. The government has exploited fault lines of identity politics in the Northeast as a ploy to distract from important issues that adversely affect all of the Northeast, like the amendments to the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act. There have been eruptions of violence along ethnic lines not only in Manipur but also along the disputed border between Assam and Meghalaya, and between Assam and Mizoram, where sub-regional identities have been pitted against each other. The atmosphere has never been as polarized as it is now.

This ethnic polarization in the Northeast is something the BJP does not know how to deal with, and that can get in the way of its own Hindu nationalist agenda. The party would rather curb the growth of Christian missionary movements in the region, which continue to make deep inroads, and project Muslims as a common adversary of the people like it has to its advantage across much of India. Still, to expand its reach in Christian-dominated states like Mizoram and Nagaland, the BJP has used the ploy of an ostensible Hindu-Christian solidarity that it has resorted to in Kerala. A BJP leader and former legislator of the Mizo National Front warned against Bangladeshi Muslims in Mizoram, claiming that “only Hindus would come to the aid of Christians.” In Nagaland, similar sentiments led to a Muslim man being lynched to death in a town square in March 2015 after he was accused of raping a minor. Local Hindutva groups are already acting as vigilantes against “love jihad,” a supposed conspiracy by Muslim men to seduce, marry, and convert Hindu women for their own demographic gains. It is very likely that a big-budget propaganda film with an anti-Muslim narrative set in the Northeast—doing here what the inflammatory movie The Kerala Story did in the context of South India—will soon be made.

In Assam, where anti-outsider sentiment has built up since the 1960s largely along linguistic lines, the BJP has placated majoritarian anxieties by further bullying the local Muslim minority. In the last five years, Muslims have been evicted from their homes on flimsy excuses, an act allowing the voluntary registration of Muslim marriages has been repealed, and the government has passed a law retroactively criminalizing child marriage and consigning offenders to new detention centers meant for “illegal” foreigners—measures understood to target the Muslim community.

But such targeting of Muslims brings its own complications. Through the winter of 2019 and 2020, India was swept by protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), passed by the Modi government, which allowed granting Indian citizenship to only non-Muslim immigrants from the Muslim-majority countries of Bangladesh, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. In the rest of India, the protestors took issue with the non-secular nature of the law, setting a precedent for possible future disenfranchisement of Muslim citizens on the basis of their religion. Assam saw massive protests against the BJP government too, only here they were based on fears that the law would allow an influx of Bangladeshi immigrants and so threaten the identity and existing demographics of the state.

Bengali Hindus in Assam, many of whom came to India from Bangladesh, have already been declared non-citizens by foreigners’ tribunals, kangaroo courts set up by the Assam government, or marked “doubtful” voters by the Election Commission of India. Despite their being an important vote bank for the BJP, many Bengali Hindus have been excluded from the National Register of Citizens (NRC), another BJP-led effort originally intended to target and disenfranchise the Muslim population, and have been detained or stripped of access to government welfare as a result. On this, too, the BJP government faced significant pushback.

Yet, despite the unintended consequences and backlash from the CAA and NRC, the BJP won the 2021 Assam elections with greater numbers than before. When the Modi government released framework rules for the CAA in March this year, taking the next step in implementing the controversial law, protests in Assam were far more subdued than the earlier ones.

Elsewhere in the region, where the CAA aroused similar anxieties over a possible influx of outsiders, the BJP managed to douse the fires by exempting from the purview of the law tribal areas with special protections under the Sixth Schedule, as well as areas under the inner-line permit system that regulates the entry of outsiders. Another potential flashpoint could be the Uniform Civil Code (UCC), which the BJP apparently intends to impose across all of India. The UCC, again intended primarily to target Muslims, would bring all Indian citizens under uniform personal laws regardless of their religion—yet it is also deeply divisive and complicated in the Northeast, where myriad communities hold dear to the traditional customs they are currently able to follow, and the customary laws and religious practices of Hindu, Christian, and indigenous communities overlap significantly. Assam’s chief minister, Himanta Biswa Sarma has said that his state government will exempt tribals from following such a code, but the inflammatory potential of the UCC remains. The Modi government’s abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir has led to fears of similar action in the Northeast, which is allowed several accommodations under Article 371 that recognize various tribal and customary laws.

In Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and Tripura, there has been growing support within tribal communities for stripping those among them who have converted to Christianity from Scheduled Tribe status, which comes with special protections and reservations. Hindu tribal groups and ones following various indigenous faiths have been radicalized by BJP’s ideological parent, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), to act against Christian proselytization. This effort is primarily run through educational institutions, including the RSS-run Ekal Vidyalayas, which impart Hindu nationalist philosophy to tribal children and train them to counter Christian-run schools. In the early months of the Manipur conflict, extremist groups that patronize the indigenous Sanamahi faith, practiced by a section of the Meiteis, attacked members of tribal communities and destroyed a large number of churches—estimates vary between 150 and 300—including ones that served Meitei Christians. They have also forced Meitei Christians to return to the Sanamahi faith by making them sign conversion affidavits and burning their bibles in what they described as acts of ghar wapsi, or homecoming—the preferred Hindu nationalist term for the reconversion to Hinduism of Indian Christians and Muslims.

The BJP’s majoritarian playbook, bolstered by its push for the region’s development, has proven largely successful in the Northeast. The BJP administrations in Delhi and the Northeastern states have invested heavily in promoting tourism and improving connectivity in the region, with long-term plans to make the region a trading thoroughfare connecting India to Southeast Asia. The BJP also has plans to promote mineral extraction, hydropower generation, and palm oil plantations, which it touts as economic boons without heed of the ecological costs. Local communities have largely welcomed these announcements, and regional parties have not been able to challenge the BJP even on their home turf—Mizoram being the only exception to this.

Yet the BJP has not fully understood the region’s complex ethnic and linguistic dynamics, or the dangers of heedlessly manipulating them, as the conflict in Manipur has shown. For the people of the Northeast, many of its intellectuals would argue, this national election is just business as usual, with pockets being stuffed and potholed roads (temporarily) fixed. However, every act of majoritarianism in the region is slowly changing its people and politics. The Northeast might have finally got more roads and bridges, but they have come at the cost of our relations with each other. With election predictions pointing heavily to a return to national power for Modi and the BJP, the people of the Northeast might expect greater connectivity with the rest of India, but with certainly more disunity among themselves.

Makepeace Sitlhou is an independent journalist and researcher with a special interest in the Indian Northeast, reporting on politics, gender, governance, conflict, society, culture, and development.

This article is part of “Modi’s India from the Edges,” a special series by Himal Southasian presenting Southasian regional perspectives on Narendra Modi’s decade in power and possible return as prime minister in the 2024 Indian election. The article is distributed in partnership with Globetrotter.