The chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 was unforeseen by the Biden administration as late as the beginning of that month, according to a new book by Atlantic staff writer Franklin Foer.

As of August 1, a month before completing the withdrawal, the Biden administration reportedly still believed that an orderly transition of power to a governing coalition between the Taliban and the government of President Ashraf Ghani was possible.

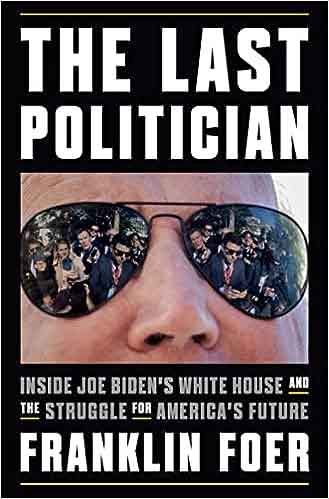

In an excerpt of “The Last Politician: Inside Joe Biden’s White House and the Struggle for America’s Future” adapted for The Atlantic, Foer depicts U.S. President Joe Biden as being unfailingly stubborn and arrogant to the end of the disastrous U.S. withdrawal.

In an excerpt of “The Last Politician: Inside Joe Biden’s White House and the Struggle for America’s Future” adapted for The Atlantic, Foer depicts U.S. President Joe Biden as being unfailingly stubborn and arrogant to the end of the disastrous U.S. withdrawal.

Biden was personally involved in solving problems at the Kabul airport during the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, directing people on the ground to find ways to get Afghans at risk out of the country, according to the book released Tuesday.

The excerpt, “The Final Days: Joe Biden was determined to get out of Afghanistan — no matter the cost,” recalls the U.S. troop withdrawal in August 2021.

The book’s release comes as the U.S. marks the 2-year anniversary of the chaotic withdrawal, one of Biden’s first major foreign policy moves as president. House Republicans have been investigating the withdrawal, which they dubbed “disastrous.”

Foer wrote that as the U.S. pushed to evacuate Americans and others in Kabul, “Biden would pepper” former Ambassador to Afghanistan John Bass “with ideas for squeezing more evacuees through the gates.” Bass was called on by the State Department to lead the evacuation effort in Kabul.

“The president’s instinct was to throw himself into the intricacies of troubleshooting. Why don’t we have them meeting in parking lots? Can’t we leave the airport and pick them up?” Foer wrote.

The book also recalls that Biden himself and national security adviser Jake Sullivan were flooded with requests from Americans to help certain people in Afghanistan, with some claiming that if Sullivan did not do anything, their deaths would be on his hands.

“Throughout late August, the president himself was fielding requests to help stranded Afghans, from friends and members of Congress. Biden became invested in individual cases. Three buses of women at the Kabul Serena Hotel kept running into logistical obstacles,” Foer wrote. “He told Sullivan, ‘I want to know what happens to them. I want to know when they make it to the airport.’”

“When the president heard these stories, he would become engrossed in solving the practical challenge of getting people to the airport, mapping routes through the city,” Foer wrote.

After the hectic images out of the airport surfaced, Biden told the situation room to fill planes with evacuees and especially focus on what the administration deemed “Afghans at risk,” including reporters, teachers and the girls robotics team that would all be targets under the Taliban, the book details.

Foer wrote that “in the caricature version of Joe Biden that had persisted for decades, he was highly sensitive to shifts in opinion” but that the “criticism of the withdrawal caused him to justify the chaos as the inevitable consequence of a difficult decision.”

“So much of the commentary felt overheated to him. He said to an aide: Either the press is losing its mind, or I am,” he wrote of Biden.

Biden’s faith in his decision was never shaken, except when a relative of a U.S. service member killed in the terrorist bombing at the Kabul airport on August 26 screamed at him to “burn in hell.” The remains of troops were sent to Dover Air Force Base, when Biden was told to “burn in hell” by a family member of one of the 13 fallen service members in Kabul, the president reportedly asked then-White House press secretary Jen Psaki if he should have handled everything differently.

In the lead up to the withdrawal, the White House had “plans for catastrophic scenarios, which had been practices in tabletop simulations,” according to Foer, “but no one anticipated that they would be needed.”

On Aug. 14 that year, the book recalls Blinken calling then-president of Afghanistan Ashraf Ghani about what might happen if the Taliban invaded Kabul before the end of that month. Ghani told Blinken, “I’d rather die than surrender.”

But, when Sullivan relayed the news to Biden that Ghani had in fact fled the country, Biden “exploded in frustration: Give me a break.”

The book recalls that just before the withdrawal, the White House was emptying out for summer vacations, which are typical in August. Foer, former editor at The New Republic, wrote that at the time, there was talk of Secretary of State Antony Blinken flying to Doha, Qatar, to preside over the signing of an accord that would “wheedle the two warring sides” in Afghanistan into an agreement that included the Taliban.

Instead, Foer writes, “Biden’s inner circle could see that the legacy of the month would stalk them into the next election — and perhaps into their obituaries.”

Foer’s book is an insider account of Biden’s first two years in office is made up of almost 300 interviews between November 2020 and February 2023, according to Politico.

By the end of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021, Biden was sure he made the right decision after watching the events unfold in the Situation Room.

“Biden did not have time to voraciously consume the news, but he was well aware of the coverage, and it infuriated him. It did little to change his mind, though, Foer writes. “In fact, everything he had witnessed from his seat in the Situation Room confirmed his belief that exiting a war without hope was the best and only course.”

Foer recounts an unflinching look at the previously untold timeline of events leading up to the withdrawal and the aftermath of it.

In the excerpt, Foer depicts a scene that went viral of the withdrawal: when dozens of Afghans climbed onto the side of a jet to escape the country.

“Only after the plane had lifted into the air did the crew discover its place in history,” Foer writes. “When the pilot could not fully retract the landing gear, a member of the crew went to investigate, staring out of a small porthole. Through the window, it was possible to see scattered human remains.”

Multiple people were killed during the U.S.-led airlift from Kabul International Airport. The withdrawal received heated criticism, especially from Republican lawmakers who have called for investigations surrounding the departure. Within days of the withdrawal, Biden’s poll numbers went down, with a majority of Americans disappointed in his handling of the withdrawal.

When former ambassador to Afghanistan John Bass touched down in Afghanistan after the plane’s departure to lead the evacuation effort, he toured the gates of the airport where he was greeted “by the smell of feces and urine, by the sound of gunshots and bullhorns blaring instructions in Dari and Pashto.”

“Dust assaulted his eyes and nose. He felt the heat that emanated from human bodies crowded into narrow spaces,” Foer writes.

Biden would shower Bass with ideas to evacuate more people.

“The president’s instinct was to throw himself into the intricacies of troubleshooting,” Foer writes. “‘Why don’t we have them meet in parking lots? Can’t we leave the airport and pick them up?’ Bass would kick around Biden’s proposed solutions with colleagues to determine their plausibility, which was usually low. Still, he appreciated Biden applying pressure, making sure that he did not overlook the obvious.”

Biden believed that unlike his predecessors, he could rise above pressures from the military and foreign policy establishments to finally withdraw the United States from an unwinnable mission in Afghanistan, the book said. In addition, the State Department believed it would be able to keep the U.S. embassy in Kabul open after the withdrawal.

By August 15, Taliban fighters began entering Kabul, including the presidential palace, with little resistance from Afghan soldiers while Ghani fled Afghanistan without providing advance knowledge to the U.S. government.

The White House, backed by the CIA, did not adjust its posture despite U.S. Central Command head Gen. Frank McKenzie warning a week earlier that Kabul could be surrounded by the Taliban within a month, the book said.

As of August 12, the US intelligence community still did not think the Taliban would try to storm Kabul until after the planned U.S. withdrawal on August 31, the book alleges.

Foer then describes how the Biden administration, lacking will and resources, unwittingly fell into relying on the Taliban to act in good faith and keep order across Kabul while the U.S. evacuation proceeded.

By mid-month, hundreds of thousands of desperate Afghans from the countryside were flooding into Kabul to escape retribution from the Taliban and trying to find a way out with the withdrawing Americans, the book said.

The Biden administration believed it could avoid a repeat of the similarly disastrous U.S. withdrawal from Saigon in 1975, but the situation at the Kabul airport quickly worsened, complete with chaotic scenes of Afghans’ grisly deaths as they attempted to board airplanes and flee, the book said.

The situation was further complicated when 13 US service members and dozens of Afghans were killed in terrorist bombing explosions outside of Kabul airport.

Blinken Admits U.S.’s Lack Of Preparedness For Hasty Afghanistan Withdrawal

An earlier media report said:

The rapid fall of Kabul in 2021 took the United States by surprise and showed deficiencies in the U.S. State Department’s preparedness for the worst-case scenario in Afghanistan, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken has said.

Blinken spoke at a staff meeting after the White House released the results of an after-action report on the Afghanistan withdrawal.

“This [the fall of Kabul] was seen as a very low probability, but obviously, potentially very high impact event and more could and should have been done to prepare for it,” Blinken said, as quoted by media that had access to event.

Blinken spoke, as cited in the report, about the five lessons derived by the State Department from the review spanning from January 2020 to August 2021. In addition to poor planning, this included “competing and conflicting guidance” from Washington and lack of clear authority during evacuations, insufficient tracking of Americans in Afghanistan, and the U.S.’s not wanting to “send the wrong signal to Afghans and to the [US-backed Afghan] government,” which eventually “inhibited” Washington’s own contingency plans.