In a stirring speech to his fellow lawyers on the occasion of Independence Day, Chief Justice D Y Chandrachud, underscored the importance of eliminating the barriers to accessing justice and said the history of the Indian judiciary has been the history of the daily struggles of the Indian people…He said the “law exudes human interest and responds positively to the plight of every individual in our society_ regardless of their social and economic background.”

But how has this actually played out in some of the most disadvantaged communities of India? A story from Bastar, where a broken justice system prevails …

*****

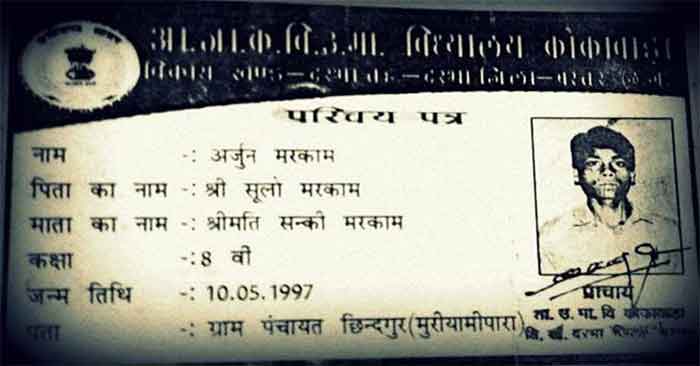

Seven years ago, on the intervening night of August 15-16, a young Adivasi boy was killed near Chandameta village in Bastar. The news of his killing was flashed by the Chhattisgarh police under a statement ‘Notorious Maoist Arjun dead on Chhattisgarh-Odisha border.’

The statement claimed Arjun was a ‘dreaded Jan militia commander,’ ‘a member of the Machkot Local Organization Squad’ and that his “dead body with weapon and many other items” was recovered from the forest after an hour-long gunbattle the District Reserve Guards (an anti-Naxal force comprising of Adivasi youths, many of whom are surrendered Naxalites) and the Special Task Force of Chhattisgarh police had with Naxalites.

Arjun, according to the police, was involved in three crimes: blowing up an ambulance during the 2014 Lok Sabha polls in which seven people died, the killing of a sarpanch in Koleng village which is the nearest roadhead to Chandameta and also the murder of another villager from Kadanar.

In a region where the major news of all such operations and those related to the conflict comes from official sources and where the Adivasis are viewed and depicted as a rogue community, this police version of an encounter was amplified by major newspapers in their reports.

What mainstream media persons were not told and what emerged only later was that Arjun was a school going boy, an under trial who had been battling these false charges since 2015 and had been regularly attending the juvenile justice court. As his lawyer, belonging to the Jagdalpur Legal Aid Society remarked, how was it conceivable for a “hardcore dreaded Naxalite” to be regularly attending court hearings? Arjun had appeared in court on July 27 and his next scheduled hearing was August 30. He was killed in a so-called encounter before he could make his next court appearance.

The Jagdalpur Legal Aid Society (JagLAG), which was set up in 2013 comprised a group of lawyers, who offered free legal services for the Adivasis of Bastar. They had been looking at how the conflict and concerns of security overshadow human rights abuses being perpetrated on the Adivasis.

Whilst the Hindustan Times of August 18, 2016, did carry a few sentences quoting the lawyers’ concerns and questions about this fake encounter, there were scarcely any narratives by Arjun’s family members on what had happened.

His father, Sulo, who later submitted a writ petition demanding an independent judicial enquiry to facilitate giving of evidence by the family, told activists and lawyers that on the night of August 15, the police and security forces, in a most brazen act of lawlessness, entered their home and forcibly took away his son. Arjun’s hands were tied behind his back; his father Sulo, mother Sanki, wife Pakyo holding an infant son Karsan and two sisters Jhunki and Pando all witnessed the way he was dragged away despite their anguished cries, he said.

Sulo who went in search of his son the next day, was told by villagers of Koleng that they had seen the police with a body wrapped in the familiar black tarpaulin that is used by security forces to ferry bodies after an encounter.

The family waited at the Durba police station all day and late at night Arjun’s body with visible gunshot marks as well as injuries indicative of torture, was returned to them.

On August 22, a few days after this horrendous violence, Sulo relocated his family to Palenar because of continuing intimidation by the police. His daughter Jhunki was forcibly taken away and detained at the Livelihood College in Dantewada and it was put out that she was a surrendered Naxalite.

The government has a policy whereby “misguided youth” can be weaned away from Naxal ideology through surrender and then given training for rehabilitation. A cash incentive is also provided. Under this policy some former Naxalites have surrendered, some have been inducted into the District Reserve Guards, but like encounters, many surrenders are fake. There are instances of people who have never been Naxalites being illegally detained, under the ploy that they have voluntarily surrendered.

Soni Sori, the noted Adivasi activist, accompanied by an NDTV journalist had visited Jhunki in the college. The young Adivasi woman categorically denied the police story and said she wanted to go home. She was allowed to do so only three months later. Meanwhile her father was often assaulted or then a bid made to coerce him into silence by offer of a job or land by the police.

These fears prevented him from filing an official complaint and it was only on January 2, 2018 that he filed his petition through lawyers of JagLAG.

The only boy among six siblings, Arjun had been enrolled in the Koleng school, a three hour walk from his village, where he studied up to class IX. He had failed in Hindi and was trying to clear his exam externally and was also helping his father working in the fields.

On May 16, 2015, as he was returning from the Tokapal market where he had gone to sell a goat, he was abducted by the police and kept in the Koleng school in illegal detention. When he failed to return home his father went in search of him and filed a missing person complaint. Fearing that his son might be tortured, because every Adivasi living in Chandameta is viewed with suspicion by the police as a suspected Naxalite, Sulo approached the Additional District Judge in Jagdalpur, informing him his son had not been produced before any magistrate in accordance with the law.

Almost as if in response, the Durba police then presented the boy, as one Arjun, son of Kordi and aged thirty, and showed him as an accused in an ongoing case of blowing up an ambulance.

The clear discrepancies in age and name of the father should have been called out as one of mistaken identity since Arjun was a minor boy studying in a local school at that time, but as a JagLAG lawyer pointed out this arrest of a minor, shown to be an adult was just the beginning of a collapsing legal system.

In contravention of the law, he was not taken before the magistrate but held in illegal detention in a school. The lawyer told me illegal detentions of Adivasis by the Central Reserve Police Forces and the police routinely take place in Bastar in most unusual paces_ in CRPF camps, schools, colleges and even toilets.

Arjun was sent to jail to live among adult convicts even though he was a minor at time of arrest. He was given a transfer to a juvenile justice home only four months later and was eventually given bail on December 30, 2015.

Why was Arjun singled out by security forces? His father had emphasized to the legal team that he had tried hard to keep Arjun safe in the risky spaces of a Naxalite zone by giving him an education. But did these very aspirations turn dangerous?

Sori had told me that Arjun came under the scanner because “woh padha likha tha.. Agar gaon ke logon ko pakkad ke le jaata toh woh sawal karta. (He could read and write.. And question. He had begun raising questions when police took people away.)

She added, “He was unafraid.” That was enough for him to be branded as Naxalwadi or for the police to see him as potential Naxalwadi.

After his son’s cruel killing, Sulo has been forced to lead an even more precarious existence. Forced to relocate twice, he found it difficult, Sori told me, to procure food supplies because he didn’t have a ration card. But it was his relentless search for justice that was the most heart-breaking aspect. After filing his petition, he would visit Sori to ask after the case and beseech, “Mera kasoor kya tha?” What was my fault.

In May this year the High Court of Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh dismissed the petition and Sulo’s plea for an independent enquiry. The judge said there was no evidence to show Arjun was taken away by the police and shot dead.

He said neither the petitioner nor his family members have made any complaint regarding the atrocities and killing of his son to higher authorities. This statement seems to be in total disregard of Sulo’s pleas in which he says the family has been harassed, subjected to police torture and for his own plea requesting safety.

Arjun’s case was one among the hundreds of cases dismissed by the High Court in Bilaspur, during the months of May June and July in which Adivasis were seeking justice from alleged atrocities perpetrated on them by the state agencies.

Among the cases dismissed was the one in which 17 Adivasis were allegedly brutally killed by security forces in Singaram on January 8, 2009.The incident occurred during the reign of the Salwa Judum, a vigilantist group working with the police. The Salwa Judum was later banned by the Supreme Court. The incident had also been taken up for consideration by the Human Rights Commission.

Also dismissed was the Peddagellur mass rapes case, filed on November 1, 2015, under the amended rape laws and Protection of Children Against Sexual Offences. Adivasi women in a remote hamlet of Bijapur district had come forward with huge difficulty to file FIRs against security forces after suffering mass physical and sexual assault and looting during a combing operation. After the filing of the FIRs when investigation was to begin, noted lawyers and a team of officials from the National Commission of Scheduled Tribes had raised the crucial question. Can there be any expectations of justice if the perpetrators _the same police and security forces_ are also part of the inquiry?

What does the dismissal of these hundreds of cases tell us of the access to justice for the poor Adivasis in Bastar? Does the bogey of security concerns override and trump even the most basic of human rights?

As a lawyer of the JagLAG team had explained, Arjun’s case illustrates how at every juncture and process the law in Bastar failed to protect the rights of an Adivasi boy and thereby failed the precepts of the Constitution.

All the grieving father, Sulo Kashyap, asked for was an independent judicial inquiry into an extra judicial execution of his son to facilitate the giving of evidence by family members and other eye witnesses and thereafter punishment of the guilty in accordance with the law.

But here too it was futile. Expectations of justice, it would appear, remains insurmountable for the Adivasi of Bastar.

Freny Manecksha is author of the book Flaming Forest, Wounded Valley Stories from Bastar and Kashmir