The traditional Marxist critique of ideology has understood both the functional and epistemological dimensions of bourgeois ideologue’s claims. This tradition has always emphasized how ideas are both conditioned by the historical conjunctures and class positions of the people and institutions that materially embody them, but also – and equally important – how, under class societies, the economically dominant class, in whose control the rest of the political, juridical, and ideological institutions are under, has to necessarily distort the world’s understanding of itself so that the vast majority of people, whose class interests are diametrically opposed to theirs, can consent to this topsy turvy image of the world. As Marx and Engels noted early on in their theoretical development,

If in all ideology men and their circumstances appear upside-down as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-process as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-process.

This structurally necessary ideological inversion will later be labeled by Engels false consciousness, a condition where the people are unaware of the “real driving forces which move [them], [instead] imagin[ing] false or apparent driving forces.” This prevents bourgeois ideologues from properly understanding the world – it subdues their ability to obtain truth in their work. However, this is far from being only a question of errors in thinking, that is, the problem of ideological false consciousness, contrary to popular belief and those of the post-modernized Western “Marxist” specialists, is far from being merely one of consciousness. The inverted character of ideologue’s ideas is a reflection of an objective social order that requires its inhabitants to think of it in deliberately inverted ways. In short: the ‘error in thinking’ is an objective necessity for our social order, a social order that requires the generalization of mistaken views of itself for its own reproduction.

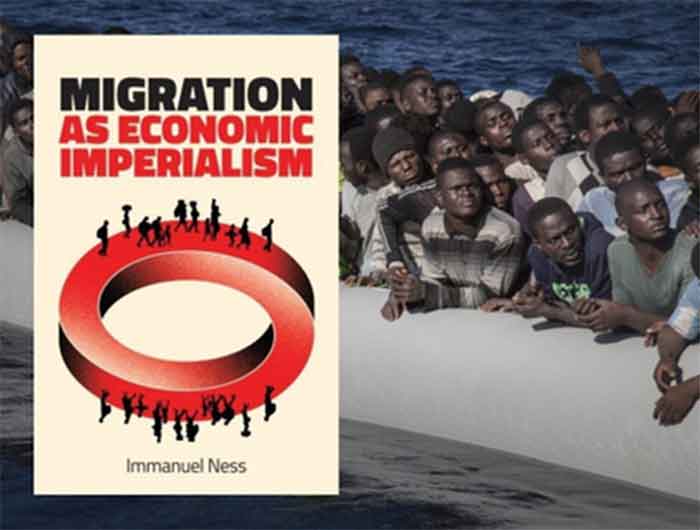

The conventional bourgeois-imperialist narratives on migration and migrant labor, a phenomenon which affects around 3 billion people (approximately 40% of the world), is filled with these ideological inversions. Immanuel Ness’s book, Migration as Economic Imperialism, does an exceptional job at exposing how these ideas emerge of out the capitalist-imperialist system (and not out of some mythical disinterested and bias-free scientific observers). He shows us how these ideas distort reality, providing us with an upside-down image of the real world. And finally, he shows us who benefits, i.e., what class and social system is upheld by the systematization of these ideological contortions. The book is, in short, a quintessential example of what Marxist scholars should be doing in the battle of ideas: exposing the hollow falsity of bourgeois narratives, and replacing these with the truth – which, as we know well, is always on the side of the revolutionaries. While this last point might seem swaggering, it is not our fault, as Che Guevara is often attributed to have said, that reality is Marxist.

The conventional imperialist narrative on migrant workers holds that they benefit the global economy, the global north countries of destination, and the global south countries of origins. Through remittances and the skills migrant workers obtain in the global north, so the imperialist narrative goes, they can help develop their countries of origin. Remittances are painted as “a leading form of economic development for poor countries” by International Development Agencies, the World Bank, and other imperialist institutions.

After the migration boom of the 1990s that followed the overthrow of the USSR, the increased flow of remittances led bourgeois specialists to hold that this was a far more preferrable alternative to the old school ‘foreign aid’ that kept poor countries dependent on rich ones (the system that devised mechanisms of debt trapping and structural adjustment programs that kept global south countries poor and indebted, of course, was never questioned).

In addition to remittances, the conventional imperialist narratives held that a stratum of higher skilled migrant workers were capable of developing new skills in the global north. These skills, so the myth goes, are taken back to the origin country and used to fuel their development and fight poverty.

Are these narratives true? Do they actually correspond to the reality they attempt to explain? As you could’ve guessed it, they are about as true as any of the other capitalist myths. Which means, from the standpoint of a comprehensive analysis of the world as it actually exists, these claims are not true at all. In fact, their conclusions turn reality upside down; as the Athenian oligarchs once wrongly accused Socrates of doing, they are the ones that make “the worst appear the better cause.” They make migration, which benefits almost exclusively the elite of the imperialist countries, appear as a beneficial phenomenon for those poor souls forced into it by the conditions their countries have been subjected to after centuries of imperialist plunder and colonial and neocolonial domination.

In reality, as Manny eloquently demonstrates, “remittances do not improve the standard of living for most inhabitants living in poor countries and do contribute to economic imbalances which engender higher levels of crime and violence.” “Remittances themselves,” as Manny shows, contribute to the erosion of the agrarian sector in southern economies as they constitute a form of rent for many residents in origin countries who are dependent on the continuing flow of remittances… [an] unreliable source of income.”

Additionally, even when certain migrant workers obtain new skills in the global north, many of them do not return home – skilled migrant workers, as Manny notes, “are more likely to be provided with legal status than low-wage workers.” This leads to what some scholars have called ‘brain drain,’ the systematic flight of skilled workers, scientists, and technicians from their countries of origin in the global south (where they often got their education) to the countries of the imperialist global north. However, even when these skilled workers do go back, Manny demonstrates that they often end up working in “niche economies which do not contribute to improving the lives of most residents there but are directed to building networks with international business … that benefit a small fraction of elites as the majority of inhabitants remain mired in poverty.”

So, for the imperialized countries of origin, where exactly are the benefits of migration? Besides the outliers in the elite that are benefited, the reality is that there are none. “If migration were beneficial to development [in countries of origin],” as Manny notes, “then countries with high migration would not be suffering the highest poverty rates, or would at least be seeing improvements outstripping those countries that were not following a migration-development strategy.” The evidence shows that the opposite of the conventional migration-development paradigm is true – migration helps to keep poor countries poor while enriching rich countries with a pool of cheap labor that they can superexploit. “The ten-leading remittance-receiving nations,” for instance, “are amongst the poorest states in the world.”

“The primary dynamic of migration,” as Manny shows, “is rooted in the political economy of imperialism, which subordinates poor regions of the Global South.” Contemporary migration is, therefore, a product and central component of imperialism. It provides for imperialist countries, whose rates of profits with their national working class have been on a steady decline, a cheap pool of labor to superexploit. These are workers, many undocumented, who are forced to break with their families by the hundreds of millions in search for jobs that pay them pennies on the dollar of the already exploited global north workers. They frequently take up the most dangerous jobs and are forced to do these under the most precarious conditions, with very little bargaining power. They are often the recipients of xenophobic attacks and derogatory racist remarks, a phenomenon produced by the elite of the global north to convince their native workers (themselves struggling to get by), that their enemy is the migrant, not their boss.

An interesting paradox arises here: while migrant workers have become an indispensable component of the imperialist economies for which they provide a cheap pool of labor to superexploit, these same workers are treated with the utmost expendability – evidenced in their working conditions and racist treatment. This is a phenomenon some scholars have called the ‘dialectics of superfluity,’ where human life and labor becomes simultaneously indispensable and expendable for capitalism. It is a condition that, while general in the working class, is intensified in migrant workers and oppressed peoples.

Things don’t have to be this way. In fact, it is impossible for them to continue this way forever. The world and everything in it are in a constant state of flux, where all is interconnected to all and contradiction functions as the engine of historical motion. These objective contradictions in the global capitalist-imperialist economy contain the kernels for their own supersession. The interests of migrant workers and workers in the global north are the same. Both are fighting against the same global capitalist elite. It is this same elite that exploits and oppresses them both, even if it does it to one with more intensity than the other. The interests of workers of all countries, migrant or not, are found in uniting with their class against the parasitic rulers of the world – those who destroy humanity in their pursuit of profit. As time passes and these contradictions intensify, we are seeing workers coming together to fight. We are seeing the embryonic development of class consciousness – and sooner or later – we will see in mass the moderate demands James Connolly heralded in 1907: “We only want the earth.”

Carlos L. Garrido is a philosophy teacher at Southern Illinois University, Director at the Midwestern Marx Institute, and author of The Purity Fetish and the Crisis of Western Marxism (2023), Marxism and the Dialectical Materialist Worldview (2022), and Hegel, Marxism, and Dialectics (Forthcoming 2024).

Originally published in Midwestern Marx