Contradictions don’t spare life, individual or collective, or class.[1] And, people’s life, spanning survival and struggles, don’t sit immobile. So, there’s dynamics in people’s struggle that moves on the matrix of class contradictions, and the matrix is complex. None, neither individual nor combine, neither production nor distribution, neither ideology nor economy, neither songs and dramas nor fairy tales and musical instruments, neither life within home nor in production-places – croplands, forest, riverine-estuarine-marine fishing grounds, factories – and markets can escape contradictions; and contradictions have respective dynamics, symmetrical and asymmetrical.

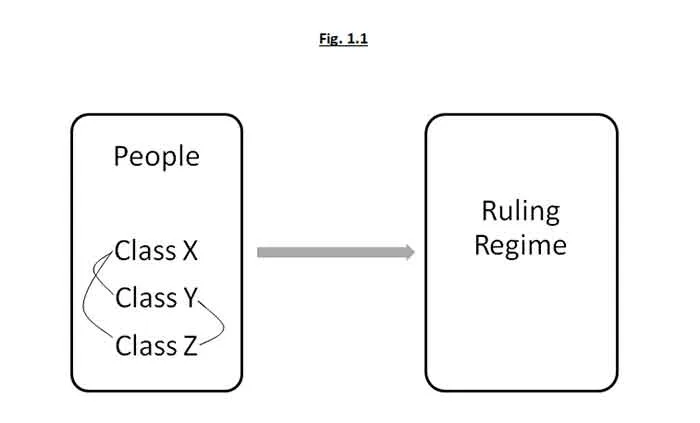

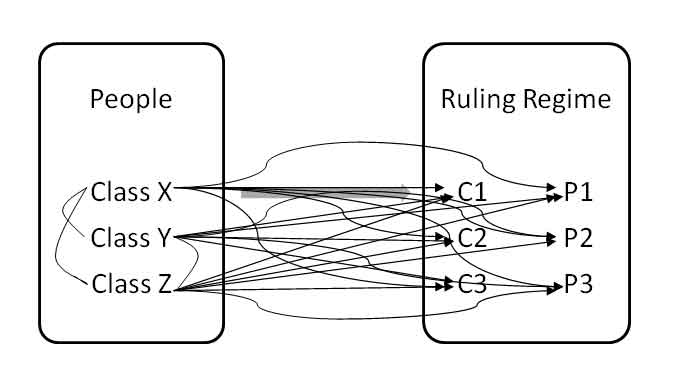

The Bangladesh people, different social classes as its constituents, had the same in their life, in their struggle for survival and emancipation in the post-mid-August-1947 – end-December-1971 period. While the classes constituting the people interacted with each other with respective class interests, the constituents and the people as a whole interacted with its opposite pole – the dominating interests, the ruling regime shown in Figures 1.1 and 1.2, and the ruling regime had constituents – classes/segments combined with common interests, ruling machine and its parts the common interests assembled, modus operandi and its parts, rules formulated, weaknesses and fractures of these, and historical limitations the common interests inherited.

Note:

- Class X, Y and Z are examples of classes

- — = interaction

Fig. 1.2

Note:

- C1, C2, C3 are examples of classes while P1, P2 and P3 are others including institutions, state machines, etc.

- — = interaction

Figs. 1.1 and 1.2

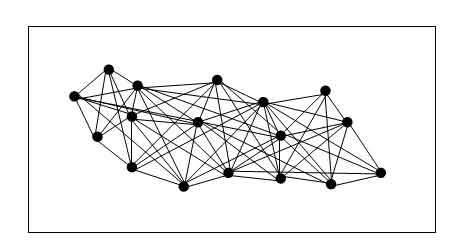

The interactions, within the camp and with the opposite camp, were in different (1) areas, (2) forms, and (3) characters. The areas included economy – labor, capital, production, distribution, consumption, surplus, appropriation, expropriation, accumulation, reproduction, natural wealth, etc. The forms included legal, illegal, constitutional, extra-constitutional, formal/institutional, informal/non-institutional, unarmed/non-violent, armed/violent, cooperation, cooption, conflict. The characters included antagonistic and non-antagonistic. These formed a complex environment as shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2

Note: The lines represent interaction with different forms and characters while the dots represent classes/factions of classes, segments of society, areas of interest/conflict

Fig. 2

This was evident in the post-mid-August-1947 – end-December-1971 period, a period of struggle against the neo-colonialism.

Culture

Culture gets lost whenever it’s defined and demarcated narrowly, whenever it’s perceived as isolated from class and class struggle. Confining culture only within the areas of literature and arts like novels, drama, poems, dance, song and painting misses the rest, which is the major part, the part influencing/shaping the other part. The issue of culture can’t be isolated from the issues of basic and superstructures.[2]

Long held aspirations of a people can’t be out-casted from the expanse of culture. These aspirations manifest in the realm of culture. These aspirations include emancipation from exploitation, freedom, recourse to injustice and repression, democratic life, peace, prosperity. People keep these aspirations alive from generation to generation. Recourse from natural calamities like draught and storm, loss of crop, famine, scarcity, economic and financial setbacks, etc. enter into the sphere of culture. Hatred and resistance – individual and class while class hatred and resistance is more powerful and effective – to highhandedness/torture of the powerful don’t stay outside of the sphere of culture. These appear not only in forms of song, drama, dance, but also as expression, and in vocabulary and symbol in commoners’ everyday life. Class struggle reverberates in culture, and in these forms and tools of culture.

Pierre Bourdieu shows the way classes use culture in respective way in defining status, and legitimize power.[3] In food, literature and art, home decor, etc., Bourdieu observed differences in judgments of taste among classes, which has political significance in a class-divided society.

There’s fundamental relation between culture and politics. Ruling classes use culture to impose its ideology for the purpose of controlling all classes hostile to it; and to control, ruling classes manipulate collective, at class level, and individual, at micro level, consciousness. Ruling classes regularly use culture to advance and cement its politics among people. This, at times, turns out vulgar melodrama. The ruling regime manufacture shallow/superfluous/superficial entertainment to distract the masses of people from the ruling regime’s illogic, anomalies, and injustices it perpetrates and lies it propagates. People’s view, attitude, traditional knowledge, aspirations, perceptions of reality that includes demands for a better, peaceful and stable life, hostilities of the system, etc. are manipulated in favor of the ruling system. People are kept over-engaged, thus making them tired, so that they can’t reflect their experiences of work, gains, losses, dispossessions, etc. It’s manipulation of brain, in Satyajit Ray’s Hirok Rajar Deshe’s king-speak, magaz dholaai, brainwashing, which leads them to perceive the “reality” ruling classes let them to perceive. But, the tact is not unlimited Inc. – without limit and bound. It, with the passage of time, as contradictions sharpen and people’s conscious engagement with class struggle intensifies, turns blunt, ineffective and useless. Consequently, people oppose it. A struggle ensues. It turns out as a contest over political space – a contest between people and ruling classes.

Classes, class struggle and contradictions impact and shape culture. At times, political struggle manifests in cultural arena, and it’s through struggle. Culture, at times, turns area of political struggle. Activities related to culture takes political form whenever it mingles with people’s struggles for (1) production and taking share of the production, (2) rights and emancipation, and (3) whenever local authorities and its hirelings can’t fulfill people’s demands. The rights include not only basic/fundamental/human rights, but also environmental-ecological and cultural rights.

Culture can’t be considered as an object or activity isolated from historical context, and economy, to be specific mode and relation of production. It’s a folly to define culture suspended from nowhere, as it grows and evolves with/within a context. To “critically comprehend a cultural text or practice”, writes John Storey, it has to be located “historically in relation to its conditions of production.”[4]

Referring to “Marx’s conception of history, contained in the now famous (and often deliberately misunderstood) ‘base/superstructure’ model of historical development”, Storey writes:

“Marx argues that each significant period in history is constructed around a particular ‘mode of production’ […] [E]ach mode of production produces: (i) specific ways of obtaining the necessaries of life; (ii) specific social relationships between workers and those who control the mode of production; and (iii) specific social institutions (including cultural ones). At the heart of this analysis is the claim that how a society produces its means of existence ultimately determines the political, social and cultural shape of that society and its possible future development. [….]

“The ‘base’ consists of a combination of the ‘forces of production’ and the ‘relations of production’. [….]

“The superstructure consists of institutions (political, legal, educational, cultural, etc.), and what Marx calls ‘definite forms of social consciousness’ (political, religious, ethical, philosophical, aesthetic, cultural, etc.) generated by these institutions. The base ‘conditions’ or ‘determines’ the content and form of the superstructure.”[5]

He explains that the “base also includes social relations and class antagonisms and these also find expression in the superstructure,” and, to take away misunderstanding, cites Frederick Engels’ letter to J Bloch:

“According to the materialist conception of history, the ultimately determining element in history is the production and reproduction of real life. Other than this neither Marx nor I have ever asserted. Hence, if somebody twists this into saying that the economic factor is the only determining one, he is transforming that proposition into a meaningless, abstract, senseless phrase. The economic situation is the basis, but the various elements of the superstructure — political forms of the class struggle and its results, to wit: constitutions established by the victorious class after a successful battle, etc., juridical forms, and even the reflexes of all these actual struggles in the brains of the participants, political, juristic, philosophical theories, religious views and their further development into systems of dogmas — also exercise their influence upon the course of the historical struggles and in many cases preponderate in determining their form. There is an interaction of all these elements in which, amid all the endless host of accidents (that is, of things and events whose inner interconnection is so remote or so impossible of proof that we can regard it as non-existent, as negligible), the economic movement finally asserts itself as necessary. Otherwise the application of the theory to any period of history would be easier than the solution of a simple equation of the first degree.”[6]

Thus, interpreting culture in a narrow sense is utterly unavailing to understand it. Struggles of the people of Bangladesh show this fact.

Note and reference:

* This is part of a write up to be included as a chapter of a planned book; and this part [part I] was published, with slight modification and with a different heading, on an earlier occasion.

- Karl Marx, Frederick Engels and their school discuss the question – contradiction. Mao’s On Contradiction, Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung (now, Mao Zedong), vol. 1, Foreign Languages Press, Peking (now, Beijing), China, 1965, provides an insight of the issue.

- P. Thompson writes in Customs in Common: Studies in Traditional Popular Culture (The New Press, New York, 1993): “Culture is also a pool of diverse resources, in which traffic passes between the literate and the oral, the superordinate and the subordinate, the village and the metropolis; it is an arena of conflictual elements, which requires some compelling pressures – as, for example, nationalism or prevalent religious orthodoxy or class consciousness – to take form as ‘system’. […] [T]he very term ‘culture’, with its cosy invocation of consensus, may serve to distract attention from social and cultural contradictions, from the fractures and oppositions within the whole.” The German Ideology by Marx and Engels (Karl Marx Frederick Engels, Collected Works, vol. 5, Progress Publishers, Moscow, erstwhile USSR, 1976), Capital, (vol. 1, Progress Publishers, 1977), Mao’s Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Arts, Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, vol. 3, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1965, Louis Dupre’s “Marx’s critique of culture and its interpretations”, The Review of Metaphysics, vol. 34, no. 1, September 1980, Philosophy Education Society of America, Washington DC, USA, pp. 91-121, and Antonina Kloskowska, “The conception of culture according to Karl Marx”, in J J Wiatr, (ed.) Polish Essays in the Methodology of the Social Sciences, Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, vol. 29, Springer, Dordrecht, 1979 provide an insight of the issue of culture. Lenin discusses culture’s aspects including its class basis, culture’s objective, material bases for its development, cultures in antagonistic societies in his works.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, tr. Richard Nice, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1996.

- Storey, John, “Marx and culture”, Culture Matters, March 27, 2018, https://www.culturematters.org.uk/index.php/culture/theory/item/2767-marx-and-culture, retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ibid.

- The portion of the letter cited here is from “Engels to J. Bloch”, Historical Materialism (Marx, Engels, Lenin), Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1972. Emphasis in the original.

Farooque Chowdhury writes from Dhaka, Bangladesh.