December 16. The Bangladesh people celebrate the day as Victory Day – a victory through vanquishing the armed forces of the neo-colonial state of Pakistan. The people tore down the state into two. The cost was wide streams of blood in the lush green land – a genocide, which is yet to be recognized properly, which means the people’s suffering and sacrifice go unheard.

While the Bangladesh people were paying prices with millions of life and honor, the people were waging a heroic armed struggle for liberation also; and an imperialist power – the United States – stood against the people’s struggle. The imperialist power was backing the Pakistan state in the state machine’s political and military effort to keep the Bangladesh people subdued. The genocide was part of that occupation war by the Pakistan state.

Chuknagar

Incidents of genocide by the Pakistan armed forces are spread over the entire country – Bangladesh. The following narration tells about pattern of killing the Pakistan armed forces wrought in many areas:

“They [the Pakistani troops] began herding the people in trucks, taking them to riverbeds and then shooting them, dumping the bodies into the rivers, where the bodies would float downstream.” [Salil Tripathi, The Colonel Who Would Not Repent, The Bangladesh War and its Unique Legacy, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2016]

One such killing spree was at Chuknagar, a southern rural community. “According to local estimates, some 10,000 to 12,000 people were killed in the span of several hours.” [“Recognize Chuknagar Genocide, demand activists”, Dhaka Tribune, May 21, 2022, Dhaka]

Following is a narrative of the Chuknagar killing-field:

“For thousands of villagers living in inaccessible parts of the delta like Rampal, Sarankhola, Morrelganj, Fakirhat, Bagerhat, and Gopalganj, Chuknagar was the transit point to reach.

“[….] On 19 May, the Muslim League [one of the political parties standing with the state machine] followers came to Badamtola and killed more than a hundred people, but only twenty-three were identified because the rest were from other villages.

“On the morning of 20 May, Chuknagar was teeming with thousands of people [….] [The people gathered there were preparing including hiring boats to go the India.]

“Around 10 a.m. […] two trucks carrying Pakistani troops arrived in Chuknagar.

“Nitai Chandra Gayen was a 24-year-old Communist volunteer. He was to meet his family in Chuknagar. He ran to warn the people gathered in the grounds when he saw the soldiers moving towards them. [….] Nitai hid in a mosque, where many people were loudly reciting the namaz, as if to show the soldiers that they were devout Muslims, and not Hindus. [….]

“Gayen said the shooting went on for about four hours. After the soldiers had gone, he slowly went to the large tree where his family lay dead […] “‘There were dead bodies everywhere’, Gayen told me [Salil, the author of the book] in Batiaghata at the college where Biswas taught. ‘In brush fire it is easy to kill people. I can’t say with any certainty how many died, but at least a thousand, and may be many more were killed. Wherever there were people, the Pakistanis shot at them. They even shot the people who jumped in the river to escape. The army then shot the boats so that the boats would drown. All I remember seeing are dead bodies’, he said.” [Salil Tripathi, The Colonel Who Would Not Repent, The Bangladesh War and its Unique Legacy, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2016]

Thaanaa Paaraa

Another was Thaanaa Paaraa [mostly spelled as Thana Para], a rural community on the banks of the Gangaa [mostly spelled as Ganga/Ganges] near a police training academy in the northern Rajshahi region. All male members of the community were asked to stand on a line, and then they were brush fired. None of the villagers survived. There were only widows and children.

Intellectuals

Peter Hazelhurst’s report in The Times tells:

“No one will ever know how many intellectuals, doctors, journalists and young men, most of who were not involved in politics, were rounded up and herded off to disappear forever.” [“Intellectuals butchered before surrender”, London, December 30, 1971]

The report with the length of 10 paragraphs, added:

“The Pakistani prisoners-of-war maintain that they know nothing about the atrocities, but evidence has been produced alleging that the Razakars [a paramilitary force the occupying Pakistan armed forces organized] were acting under the direct orders of a senior officer.”

The report mentions one mass killing of intellectuals, as it quoted Delwar Hussain, one of the prisoners in a prison camp:

Delwar Hussain “discovered that he was in a room with a score or so of other prisoners. Some of them had been tortured. Toe nails had been ripped off and toes amputated.

“After an hour they were interrogated. The prisoners identified themselves as doctors, lawyers, professors and journalists. They were forced into a bus and driven out to [a] marshlands on the outskirts of Dacca [now, Dhaka].

“The Razakars led their victims to a big tree where about another 130 prisoners were huddled. Several prisoners asked the Razakars why they were killing fellow Bengalis. ‘One of them told us to shut up and gave an order’, “finish the bastards off”, Mr. Hussain said, ‘they started to shoot prisoners with rifles, and others were simply bayoneted to death. I managed to slip the rope off my wrists and made a dash towards the river. By a miracle I escaped.”

C. S. Pandit’s Dacca, December 19, 1971 datelined dispatch, published in The Indian Express, said:

“In the last week before the surrender of the Pakistani occupation army, about 120 intellectuals including top doctors, professors, journalists, both men and women, were spirited away from their houses during curfew hours under military escort. Nothing was heard of them until about 36 bodies, with hands tied behind, were found dumped in the pits of some brick kilns.” [“Bodies of doctors, journalists, writers and professors dumped in pits”, December 20, 1971]

Sugar mill workers

In the North Bengal Sugar Mills at Natore in the northern Bangladesh, 300 workers and staff were murdered in a single day. [Dainik Bangla, February 26, 1972, report by Sakhwat Ali Khan.]

Similar incidents are hundreds, spread over the entire country – in towns and cities, in villages, rural market places, river and canal banks and banks of water bodies, in industrial areas; and many of those mass-murder incidents are documented in different forms including witness’/victims’ reports/mails to the Human Rights Commission, Geneva, press reports, interviews and memoirs. A part of these have been documented by a committee of experts/academicians, and published as document on the genocide. Moreover, a number of books have documented many of the killing flings by the Pakistan state in regions of the country in 1971. A few of the murder-businesses are referred, but most of those go un-mentioned.

How many Bengalis have you shot?

Report of the Hamoodur Rahman Commission in Pakistan tells about Pakistan’s genocide-practice in 1971-Bangladesh. A few parts from the report are mention-worthy:

Pakistan army’s [henceforth, PA] Lt. Col. Aziz Ahmed Khan, told the Commission the way Lt Gen Niazi, commander of the Pakistan army in then-East Pakistan, today’s independent Bangladesh, had ordered the genocide: “General Niazi visited my unit at Thakurgaon and Bogra [in the northern part of Bangladesh]. He asked us how many Hindus [part of Bangladesh people] we had killed. In May, there was an order in writing to kill Hindus. This order was from Brigadier Abdullah Malik of 23 Brigade.”

Brigadier Iqbalur Rehman Shariff of the PA said: During a visit to formations in East Pakistan General Gul Hassan [of the PA] used to ask the soldiers: “How many Bengalis have you shot?”

Brigadier Mian Taskeenuddin of the PA said: “In a command area (Dhoom Ghat) between September and October, miscreants [The PA/Pakistan authority used to identify the Bangladesh freedom fighters as “miscreants”] were killed by firing squads.”

The Commission stated that mortars were used to blast two residential dormitories of the Dhaka University, thus causing excessive casualties.

The Commission mentioned “indiscriminate killing” by the PA in Bangladesh. It specifically mentioned the Comilla Cantonment [in eastern part of Bangladesh] massacre on 27th/28th of March, 1971 under the orders of CO 53 Field Regiment, Lt. Gen. Yakub Malik: “17 Bengali Officers and 915 men were just slain by a flick of one [PA] Officer’s fingers […]” Other cantonments also witnessed similar massacres.

Incidents of indiscriminate arson, destruction of houses, shops, rape, loot, aren’t referred here, as that’s another long tale of barbarity. The dastardly acts are so ugly and despicable none today admits any sort of involvement with these.

Kissinger

Whenever this genocide is referred, the names that visit memory are of Nixon and Kissinger along with the Pakistan state/leadership. In an article, written after the death of Kissinger, Arnold R. Isaacs wrote in Salon:

“The cataract of news and pontification about Henry Kissinger’s death reminds me of an email I sent out nine years ago with some notes on a book that chillingly documented — mostly from Kissinger’s own words — a piece of his record that should be getting a lot more attention. What follows is an edited and updated version of that 2014 email.

“The book was The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide by Gary J. Bass, a former reporter turned Princeton professor. Its subject is Richard Nixon and Kissinger’s pro-Pakistan ‘tilt’ in the 1971 India-Pakistan war and their astonishing indifference to the slaughter of Bengali civilians in what was then called East Pakistan (and is now Bangladesh) carried out by troops sent by their great friend Yahya Khan, then Pakistan’s president and commander in chief of its army.

“Bass documents his story largely from Nixon’s and Kissinger’s own words, as captured on the White House tapes that became notorious in the Watergate investigation. The telegram in his title, sent to the State Department by Archer Blood, the U.S. consul general in Dhaka (then called Dacca), East Pakistan’s capital city, and signed by nearly all the rest of the consulate staff, documented the atrocities and objected — vainly — to the Nixon-Kissinger policy.

“Bass is religious about not reading minds, not guessing at or speculating about Nixon’s or Kissinger’s consciousness or motivations, not going beyond the record of their words. He characterizes what they said and did, not their character. But reading their words leaves little doubt that those two between them had about as much moral consciousness as a cockroach. They didn’t care about crimes against humanity or about human suffering on any scale. A revealing example is a Nixon quote from the White House tapes: talking to Kissinger in the Oval Office in May 1971, Bass writes:

Nixon bitterly said, ‘The Indians need — what they need really is a —’ Kissinger interjected, ‘They’re such bastards.’ Nixon finished his thought: ‘A mass famine.’

“An astonishing comment. They might not have liked Indira Gandhi or Indian national policy, but what kind of person would wish mass starvation on the poorest and most powerless of India’s people?

“In Kissinger’s case, it’s particularly hard to imagine how a man who started out as a Jewish refugee from the Nazis could be as conscienceless as he was about the slaughter in East Pakistan. But the evidence in Bass’ book of his moral blindness is absolutely convincing. The same goes for Nixon. Before reading it I would have bet quite a lot of money that my opinion of either of those two men — whose policies shaped the events and the enormous human suffering I personally witnessed on the ground in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia during the last three years of the Vietnam War — could not possibly get lower than it already was. But it did.

“‘The Blood Telegram’ doesn’t just reveal Nixon’s and Kissinger’s moral thuggishness. It also explodes the tale that they and their supporters have pushed for all these years […]

“In page after page of the discussions on Bangladesh reproduced in ‘The Blood Telegram’, there is not the slightest hint that Nixon and Kissinger were pragmatically weighing national interests and capabilities against human concerns. Instead, over and over, their words make unmistakably clear that the human consequences of their policies weren’t part of the equation at all. And it’s just as unmistakable that there was no pragmatic argument for those policies anyway. Nothing Nixon and Kissinger did was going to prevent East Pakistan from declaring independence, and that was obvious at the time. [….]

“[H]e [Kissinger] and Nixon based their Pakistan ‘tilt’ in part on an expectation that the Chinese would be willing to risk nuclear war with the Soviet Union in order to protect Pakistan from India (perceived as a Soviet ally at the time). [….]

“[….] In fact, Nixon and Kissinger explicitly hoped the Chinese would threaten intervention to deter an Indian war against Pakistan. As that war began in early December of 1971:

Kissinger told the president that ‘we could give a note to the Chinese and say, “If you are ever going to move this is the time.” Nixon immediately agreed. … The president argued that ‘we can’t do this without the Chinese helping us. As I look at this thing, the Chinese have got to move to that damn border. The Indians have got to get a little scared.’

“The lawbreaking — with the full awareness of UN ambassador (and future president) George H.W. Bush, deputy national security adviser (and future secretary of state) Alexander Haig, White House chief of staff H.R. Haldeman and others — involved getting Iran (then a US ally) and Jordan to give Pakistan US-supplied weapons from their arsenals, including aircraft, which was explicitly prohibited by US law. The tapes show conclusively that Nixon and Kissinger knew such a transfer would be illegal — and both the State Department and the Defense Department told them that, in categorical terms. But they did it anyway and spoke about it bluntly, with no apparent qualms about breaking the law.

“When speaking with Nixon before a press conference, Kissinger said, ‘This military aid to Iran that Iran might be giving to West Pakistan. The only way we can really do it — it’s not legal, strictly speaking.’ Nixon and Kissinger recognized the need to conceal what they were doing: ‘We’ll have to say we didn’t know about it’, Kissinger said, adding that they could give Iran extra aid the following year in return for Iranian cooperation. On another occasion, Nixon bluntly told Haldeman: ‘We’re trying to do something where it’s a violation of law and all that.’

“After State Department officials raised the legal issue in one situation room meeting, Kissinger said scornfully: ‘We shouldn’t decide this on such doctrinaire grounds.’ An interesting viewpoint, and one we have also heard from officials of a more recent administration: Obeying the law is doctrinaire?

“Kissinger consistently reinforced Nixon’s impulse to ignore the law, but also took precautions to cover his own backside by getting Haig to compile memoranda showing that Nixon knew about and approved the illegal transfers.” [“Henry Kissinger and the genocide in Bangladesh: Low point in a career of evil”, December 10, 2023]

Standing by the side of the generals

Ishaan Tharoor writes in Washington Post:

“Kissinger is remembered keenly in South Asia for the part he and Nixon played during the bloody period that led to the emergence of the independent nation of Bangladesh in 1971.

“[….] After 1970 elections yielded a democratic victory for Bengali nationalists, a crisis ensued that culminated in a vicious crackdown by the Pakistani military on East Pakistanis — a campaign that turned into a mass slaughter of minority Hindus, students, dissidents and anyone else in the crosshairs of the army and collaborator-led death squads.

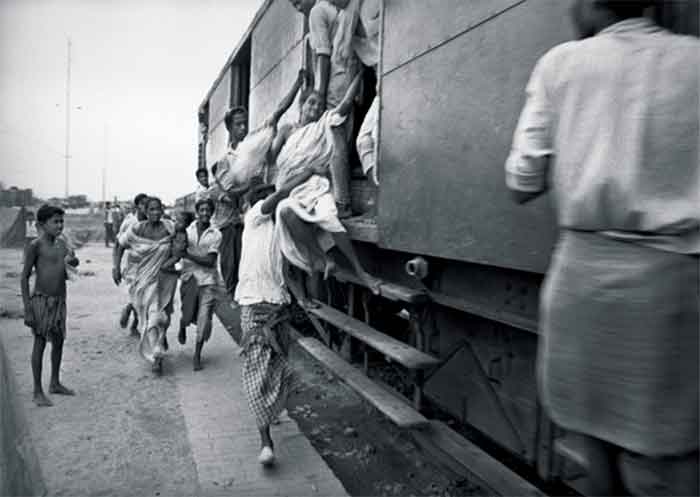

“Sydney Schanberg, the New York Times’s South Asia correspondent at the time, described the month-long Pakistani crackdown in March 1971 as ‘a pogrom on a vast scale’ in a land where ‘vultures grow fat.’ Hundreds of thousands of women were raped. Whole villages were razed, and cities depopulated. An exodus of some 10 million refugees fled to India. When all was said and done, hundreds of thousands — and by some estimates, as many as 3 million — were killed, their bodies left to rot in the rice paddies or flushed into the ocean down the region’s many waterways.

“[….] The White House, though, stood on the side of Pakistan’s generals […] Kissinger […] did not care about the national aspirations of the Bengalis of East Pakistan. Crucially, as outlined in Gary Bass’s excellent book, ‘The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide,’ he also ignored messages and dissent cables from US diplomats in the field, warning him that a genocide was taking place with their complicity.

“Neither Nixon nor Kissinger exercised any of their considerable leverage to restrain Pakistan’s generals. Instead, they covertly rushed arms to the Pakistanis — in violation of a congressional arms embargo — as India and its Bangladeshi separatist allies gained the upper hand. ‘Throughout it all, from the outbreak of civil war to the Bengali massacres to Pakistan’s crushing defeat by the Indian military, Nixon and Kissinger, unfazed by detailed knowledge of the massacres, stood stoutly behind Pakistan’, wrote Bass in his book. [….]

“‘Rather than reckoning with the human consequences of his deeds, let alone apologizing for breaking the law, Kissinger assiduously tried to cover up his record in the South Asia crisis’, Bass wrote in the Atlantic after Kissinger’s death. ‘As late as 2022, in his book Leadership, he was still trying to promote a sanitized view, in which he tactfully termed former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi “an irritant”—even though during her tenure he repeatedly called her “a bitch”, as well as calling the Indians “bastards” and “sons of bitches”.”

“Not surprisingly, news of Kissinger’s passing was treated dyspeptically in Dhaka. In remarks Thursday, Bangladeshi foreign minister A.K. Abdul Momen said Kissinger was ‘dead against the people of the then-East Pakistan’, chose to violate US laws in the support of Pakistan’s military and failed to offer an apology to the Bangladeshi nation for the atrocities that took place on his watch. [“The Bengali blood on Henry Kissinger’s hands”, December 1, 2023]

Keraniganj

Reports of mass murder, genocide, visit one’s memory while one comes across the news of Kissinger’s death.

One such killing was near Dhaka city. Thousands of Dhaka residents took shelter in Keraniganj, on the other side of the Buriganga that flows by Dhaka city, since March 26, 1971. This run of citizens from Dhaka city continued for days. The citizens assumed that the other side of the river was safe. But, on April 2, 1971, the Pakistan army cordoned Keraniganj, and made an all out assault in villages of Keraniganj. Mainly three unions [lowest tier of local government] – Jinjira, Shoovadyaa and Kalindi – were attacked. Along with acts of indiscriminate arson and dishonor, the mass killing went on. All homes of villagers were assaulted – set on fire, dwellers were brush fired. After the killers left, reports began trickling – innumerable deaths, hundreds of dead bodies scattered around bushes, groves, irrigation channels and ponds. Two such incidents were [1] 60 dead bodies were lying near a pond by a road in Mandail, and [2] 11 women were killed in a home in Kalindi. [Dainik Bangla, April 3, 1972]

Against imperialism

This genocide is integral part of the Bangladesh people’s War for Liberation.

In this War for Liberation by the Bangladesh people, imperialism stood against the people, and the people’s war stood against imperialism. Imperialism’s was its interest, which is usually expressed as imperialism’s “geopolitics”, “countering Soviet Union”. But, imperialism’s geopolitics and moves to counter Soviet Union aren’t isolated from imperialist interest. Rather, imperialist interest drives imperialist geopolitics. However, a number of questions related to this struggle standing against imperialism needs to be answered.

Farooque Chowdhury writes from Dhaka, Bangladesh.