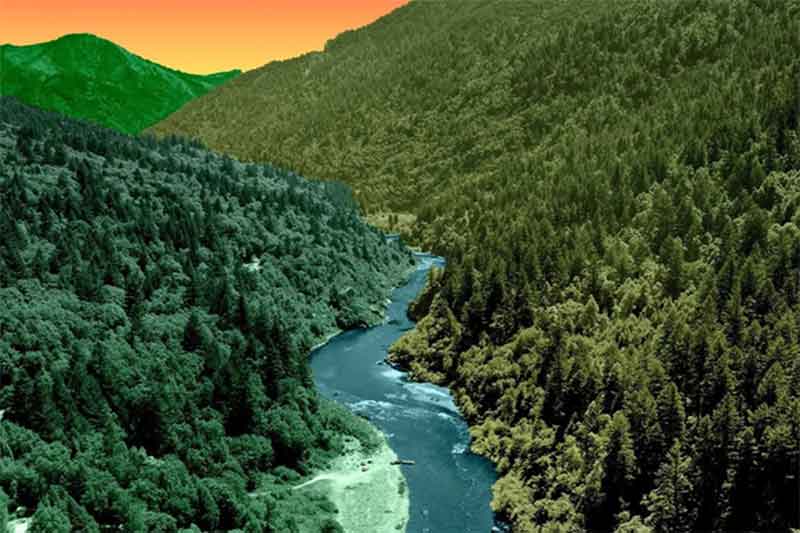

The largest dam removal project in U.S. history took an irreversible step forward earlier this month when crews opened a 16-foot-wide tunnel in the base of the Iron Gate Dam in Hornbrook, California. That event marked the beginning of the end of a decades-long effort to restore the Klamath River, which snakes for more than 250 miles through Oregon and California, to a new natural state.

“This is historic and life-changing, and it means that the Yurok people have a future,” Amy Cordalis, a member of the Yurok tribe and one of the leaders of the effort to remove the dams, told NPR. “It means the river has a future, the salmon have a future.”

Drawdown water exits what was the emergency bypass tunnel at Iron Gate Dam. The flush is designed to remove decades of silt deposits from in front of the dam and flush it downriver. Brian Gailey/KWUA

Media reports including a report by Herald and News (Klamath Falls, Oregon) said:

Members of the Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, Shasta, and Klamath peoples, among others, have long worked to convince federal regulators that the four dams on the river — Iron Gate, Copco 1, Copco 2, and JC Boyle — have done more harm than good. Originally built a century ago as part of a hydropower development blitz in the American West, they blocked salmon and steelhead trout from reaching their habitats, decimating fish populations and robbing the tribal nations of a vital food source. The dams quickly outlived their usefulness: The amount of power they produce is negligible compared to the needs of the region today.

Copco 2, the smallest of the four dams, came down last fall; that one didn’t have a reservoir, which made it relatively easy to remove. Over the next few months, Iron Gate, Copco 1, and JC Boyle will all have their reservoirs drained, returning the river water to levels not seen since the early 20th century. By the fall, the last vestiges of the dams should be off the river.

Upstream of the Iron Gate Dam, workers use pumps and high-pressure hoses to dislodge sediment from the confluence of Scotch Creek and the Klamath River (Iron Gate Reservoir). Brian Gailey/KWUA

The tribes have big plans for what comes next. An immense effort — funded, at least in part, by millions of dollars from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law — is underway to revegetate the more than 2,200 acres of land that will be exposed when the reservoirs are empty, and with more than 17 billion seeds slated for planting and at least a thousand trees ready to be flown in by helicopter. Over time, the river will slowly turn back into the vibrant, free-flowing ecosystem it once was.

Those who were on-site when the tunnel was opened this month described seeing “chocolate-milk-brown water,” a “dark purge” containing both water and sediment flow through the dam. Sediment is an existential problem, and not just for the dams in the Klamath river — human-made barriers prevent silt from traveling downriver, and the sediment buildups block dams’ release gates, reducing their ability to both generate electricity and release water. This also affects downstream ecosystems, which evolved with a steady supply of fertile new soil. Once enough sediment builds up, a dam becomes practically useless.

The removal of the Iron Gate dam, then, is not just a service to the Native peoples and ecosystems along California’s second-largest river. It is also the solution to a problem that has quite literally been building for decades.

“Being able to look at the river flow for the first time in more than 100 years, it’s incredibly important to us,” Frankie Myers, vice chair of the Yurok Tribe, told the San Francisco Chronicle. “It is what we have been fighting for: to see the river for itself.”

On Wednesday, Jan. 11, 2024, the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC) opened a reinforced emergency discharge tunnel on Iron Gate Dam for the first time in 60 years. This meticulously planned event is a significant milestone in the overall timeline of removal on hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River.

Many years of work have already been completed to get to this point. After drawdown of Iron Gate and two other reservoirs, dams will be demolished and the river will flow through a structure-free Klamath River canyon. This will be followed by several years of rehabilitation to restore the 40-mile section of river to pre-dam conditions.

The three remaining Klamath River dams slated for removal (Iron Gate, Copco No 1, and J.C. Boyle) have been in place for between 60 and 100 years. Large volumes of sediment have accumulated behind them. The opening of the Iron Gate emergency tunnel and subsequent opening of the other dams will allow for retained water to discharge carrying dislodged sediment downriver.

“We have been able to hit a really critical milestone,” said Mark Bransom CEO of KRRC. “We set out a schedule and a set of goals for ourselves going back a number of years. We have been working methodically toward this day.”

Dozens of invited guests had the opportunity to stand on the shores of the Klamath River just below Iron Gate Dam and witness the dark purge of river water escape of the tunnel. Guests came from many perspectives, with differing interests: government officials from Siskiyou County, river restoration groups, tribes, and water users were all present.

Due to limited space, these congregations were arranged in smaller groups and guided by officials from KRRC. Representatives from the Klamath Water Users Association (KWUA) including Moss Driscoll, Director of Water Policy, and Luther Horsley, a KWUA Board Member and longtime Klamath Basin irrigator, were among those present.

“I was initially in awe of the massive amount of energy being released in the 4000 cfs discharge from the tunnel,” Horsley said. “I’m hopeful Mother Nature cooperates, and the dam removal process is successful and the river habitat improves. But skeptical!”

Overall plans for the removal of the dams have been consistent with a timeline that has been in place for the last few years. However, details of schedules have to been fluid. The plan for the discharge has been adjusted several times in recent weeks following the plan originally filed with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

“The recent changes to the drawdown plans highlight water users’ concerns about the unanticipated implications of dam removal,” Driscoll said. “Our immediate concern is that releases from Upper Klamath Lake be limited to account for the stored water being released from the hydro reservoirs, which is now more than doubling the designated instream flows downstream of Iron Gate. Water cannot be used from Upper Klamath Lake to mitigate impacts of dam removal activities. We need that water to refill our refuges and have a normal irrigation season next year.”

When asked if water will need to come from Upper Klamath Lake for the flushing of the reservoirs, Bransom said, “We would love to have a little more water if things stay dry because we have a very narrow window to mobilize and flush out this accumulated sediment from behind all three dams. But we do not have any expectation that the Bureau of Reclamation or anyone else is going to welcome us requesting additional water from the lake.”

Bransom added, “We do not anticipate, nor do we ask for water that is not already in the lake that we have banked. We have been going through a series of reservoir drawdowns in coordination with the Bureau to bank a little water for the drawdown of Copco No. 1. We are requesting that we get that water back to help us to do real things.”

KRRC’s purpose of the reservoir drawdown event is twofold.

The first is to mobilize the sediment and flush it out, getting as much sediment out of the reservoirs as possible between now and mid-March.

The second is to try to reduce the risk of sloughing on steeper banks within the reservoir. Both would be accomplished by balancing the drawdown rate so that it is fast enough to flush but slow enough to not cause unneeded erosion.

“As dam removal commences, we need to acknowledge that flow management on the Klamath River has exacerbated the impacts associated with the hydro reservoirs,” Driscoll said. “Steady state flows over the past two decades created the disease hotspot for salmon. When we look at a restored river, we must appreciate the lesson we have just learned – maximizing physical habitat availability does not equate to an actual benefit to fish, in some cases the opposite.”

According to KRRC, following the drawdown events, crews will begin to demolish the concrete structure of Copco No. 1 and the earthen structure of Iron Gate Dam. The process will occur at a pace consistent with the natural flows of the river. That way if a major drainage event hits the river channel, the water will not crest over the dams causing catastrophic failure.

The current timeline shows this process to be completed by late fall 2024, before the winter weather events arrive.

An NPR report (copyright © 2024 NPR) said:

In January, an irreversible step was taken in the largest dam removal project in U.S. history. Crews opened a tunnel in one of the three Klamath River dams that are slated to be removed and started letting water flow through the lowest section of the river. It is a critical stage in a process that is expected to last through 2024. Following is the Jefferson Public Radio’s Erik Neumann report:

ERIK NEUMANN, BYLINE: The dam that was opened yesterday is the lowest on the river. It’s huge – 173 feet tall, made of earth and rock. And after a 16-foot-wide tunnel was opened at the base yesterday morning, a plume of chocolate-milk-brown water surged through, containing sediment that had accumulated over decades. Mark Bransom is the CEO of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, the organization in charge of dam removal.

MARK BRANSOM: For the first time, you know, in a hundred years, beginning today, the river is actually coming back to life.

NEUMANN: The Klamath River flows more than 250 miles from Oregon through far Northern California, where it joins the Pacific Ocean. But for decades, much of the river has been blocked by four hydroelectric dams. Several tribes up and down this river have been at the forefront of protests to remove them for the health of fish, including salmon. Amy Cordalis is a member of the Yurok Tribe and a longtime advocate for dam removal.

AMY CORDALIS: This is historic and life-changing, and it means that the Yurok people have a future. It means the river has a future, the salmon have a future.

NEUMANN: Cordalis is an attorney for the Yurok Tribe and one of a younger generation of activists who took up the fight after the pioneering work of older tribal members like Leaf Hillman. He’s a member of the nearby Karuk Tribe who helped start the campaign to take out the dams more than 20 years ago.

LEAF HILLMAN: As one generation, you know, moves on and passes on, the new generation is there to pick up the fight. And so it really has been a multigenerational struggle to remove these dams.

NEUMANN: The Klamath was once the third-largest-salmon-producing river on the West Coast. But over the past century, the salmon numbers have shrunk. The dams cut off spawning habitat and created conditions for fish diseases. Scientists are hopeful that ultimately taking out the dams will help the population rebound. Shari Witmore is a biologist with NOAA Fisheries. She helped evaluate the impacts to salmon from dam removal on the Klamath.

SHARI WITMORE: So when dams come out, we will have over 400 miles of Chinook habitat available, which we expect over time will be a greater than 80% increase in Chinook populations in the Klamath River.

NEUMANN: She says it’s also expected to be a major step in the recovery of the river’s more vulnerable Coho salmon. Reconnecting this single ecosystem, she says, will allow these species to extend their habitat. That’ll help them better withstand heat waves, disease outbreaks, and increase their genetic diversity.

WITMORE: And that creates a lot of resilience over time with climate change. And it buffers against multi-year droughts.

NEUMANN: Improving these fish populations, Witmore says, will also help killer whales in the ocean and commercial fishermen. But there are some who are concerned about the possible effects of dam removal, like many in the small community of Copco Lake. In the coming weeks, homes that were once on the lake will now be on a mudflat, as the reservoir behind the dam turns back into a narrower river. Francis Gill is a resident and the chief of the volunteer fire department. He is worried about property values going down and fighting fires without the lake as a water source.

FRANCIS GILL: Especially just with the way the wildfires have been getting the last 10 years, it is just – they just blow up so fast and get so big so quickly.

NEUMANN: There are other dams being considered for removal in the U.S., like those on the lower Snake River in Washington state. Dave Owen is a professor at UC Law San Francisco, where he teaches environmental and water law. He says while other dams might face bigger legal and political hurdles to removal, large projects like those on the Klamath do create possible models.

DAVE OWEN: But still, every time we do this and we do this at a big scale, we learn new things about the legal pathways. I think the other way it helps is it just helps people see that this is possible and that it can be highly successful.

NEUMANN: By the end of February, water will be let out of the two other upriver Klamath dams and be flowing freely through this section of the river for the first time in a century, carving a new channel for itself as it heads to the ocean. For NPR News, I’m Erik Neumann on the Klamath River.