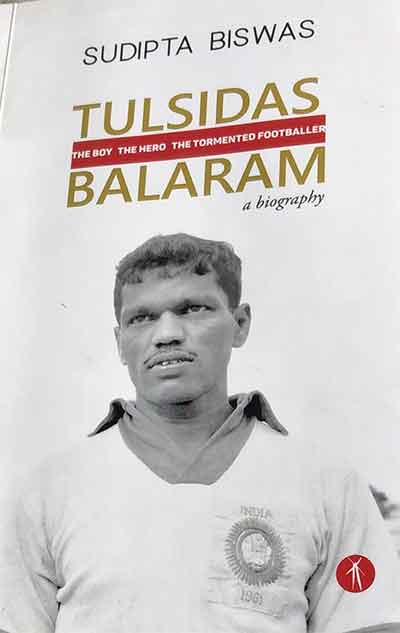

Tulsidas Balaram: The Boy, the Hero, The Tormented Footballer. A Biography. by Sudipta Biswas, Hawakal Publishers, Pg: 329, Price: Rs 550

In a country obsessed with multimillionaire male cricketers, superbly talented and emerging cricketing heroes, grandiose, cash-rich, stuffed with non-stop advertisements, quick-fire, commercially-driven IPL as an adrenaline-soaked and cathartic spectacle, and almost continuous cricket through the year, telecast on TV and mobiles, little is known about most of the kaleidoscopic greatness in other sports, especially in hockey, football and athletics.

A huge part of this sporting terrain is largely left to social indifference and media-disdain. Most of these sportspersons come from obscure small towns, and rural and Adivasi homelands, and they make it to the junior and senior squads in the national and world tournaments with sheer tenacity, resilience, dogged hard work and exceptional talent – often in the most adverse circumstances, without adequate nourishment or professional training, in rugged and humble backdrops, and against all odds. Many of them come from extremely poor backgrounds, like former women’s hockey India captain, Rani Rampal, among others, who had not even seen a drop of milk in all her childhood. Even when they succeed despite the entrenched walls of social and economic discrimination, they remain on the margins of fame and success. Few of them are glorified into national icons. A handful become moderately rich.

Amidst this relentless onslaught in this mix of celebrityhood and big, fat cash, controlled by entrenched lobbies, many great sportspersons choose to work in silence, creating and nurturing raw talent (like Pullela Gopichand), while others withdraw into total oblivion. They include, great batters like Gundappa Vishwanath and Mohinder Amarnath, spinners BS Chandrashekhar, Erapalli Prasanna, Padmakar Shivalkar, all-rounders like Salim Durrani, Eknath Solkar and Abid Ali, or hockey stars like Ashok Kumar and Michael Kindo, among others. Great leg-spinner Bishen Singh Bedi, who died recently, lived his entire post-cricket life as an authentic, truthful, honest and brave rebel – in defiance and protest – opening up the cracked mirrors of the cricket establishment, especially in Delhi, which was captured by a BJP top politician once upon a time. They never ever chose to join this cash-cow bandwagon, their greatness remained their only testimony in the history of Indian sport.

In this scenario, who would care a damn for an unknown legend in early Indian football, who played barefoot on a rugged ground in the backyard of his refugee camp, whose family could not afford him good nourishment, books or a uniform for school, or, who never really had a proper pair of boots to play his favorite game. (His first boots were given to him after a long ‘Tapasya’ near a traffic-crossing, seeking a pair of discarded policeman’s boots from an unknown and not-so-friendly traffic constable. These heavy, over-sized, tattered and impossible-to-wear boots, were fixed painstakingly by a kind and visionary cobbler in the neighborhood, who saw the boy’s talent for the game early. His name was Tulsidas Balaram: the boy, the hero, the tormented footballer.

Sudipta Biswas is a young sports writer. He writes with a trained and instinctive lucidity, very simply, and without jargons or cliches; he is often nuanced and understated, his research is impeccable, and his English-language skills are perfect. He is currently based in a small, picturesque, rural Bengal village in a humble house surrounded by trees and an endless green landscape, near Bongaon, close to the Bangladesh border, and also close to the home of great Bengali writer, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, who penned, among other famous novels and stories, the opening trilogy which Satyajit Ray turned into his first black and white cinema classics, among the finest in world cinema.

Sudipta has willfully chosen to live and work in a small village, for an excellent sports portal, ‘The Bridge’, based in Bengaluru. Earlier, he has worked in the mainline media, especially for ‘Sportstar’, based in Chennai. He does not write about cricket. He writes about all the sports which are non-cricket: badminton, football, athletics, chess, etc, and what he calls the ‘Olympic movement’ in India.

He is indeed a young and offbeat shining star among the rare and precious legends of great sports writers in India. His meticulously researched book has been done with years of hard labour, documentation of oral and written history, interviews with former footballers, witnesses and journalists, extensive travel, and while going through a pile of old newspapers and assorted material.

In Bengal, and among its famous clubs, namely East Bengal, Mohan Bagan and Mohammedan Sporting, there are three names which were the earliest legends. Two are remembered and they had a famous and successful life. One has been totally forgotten, treated with scant respect, not given the awards or recognition due to him in his lifetime, and reduced into a once-luminescent star now submerged in darkness.

The two football greats in Bengal were Balaram’s contemporaries. They made a fabulous troika of brilliant footballers. Chuni Goswami and PK Bannerjee have been house-hold names in Kolkata and Bengal for decades, while the former also became captain of the West Bengal cricket team, with his extraordinary repertoire of talent. He was, indeed, the captain of Balaram, the reclusive and best striker in his team; except for one occasion when the entire team backed Balaram and said that only he could lead them in a crucial game, and that they would play under no one but him, and not even under their captain, Chuni.

The blurb on the back cover explains this scenario: The discussion about pursuing the legendary duo of PK Banerjee and Chuni Goswami often leaves out the last component, which otherwise builds into a triad. Tulsidas Balaram is a legendary striker whose decades-long career is nothing short of an inspiring account. It also traces an era that saw football as an emotion. The Indian politics that flamed to oppress him, in fact, channeled and vitalised him with permanent fervour. Due to his ailing health, his career was brief… This book traces the geography, politics, conspiracy and emotional rage of the 1940s – a time that shaped Balaram and his love for football.

The beginning of the book is a catalytic revelation and draws you into its heady and rustic romance. “The ground at the Government Boys High School at Bolarum is almost bare. A lot of earth and gravel, and only a few spots of green on the touchlines. There are no sticks to set up the goalposts. There are no houses nearby. The neighbourhood – Ammuguda, a village built around the Secunderabad Cantonment’s British military establishment – is no better off. There is no proper road, no water, and no light of sorts. Cobblers, cycle garages, daily wage workers, and a railway station — built on the onset of the 19th century, ferrying the villagers to Hyderabad on trains running on a metre gauge line – set the locality. Menfolk, barefooted, work in a local railway factory. Most of the houses here, like Balaram’s, are dimly lit, single-storeyed, with large verandahs and courtyards…. Football rules the roost in this part. Boys do not play any other sport. They eat, sleep and play football… They are happy times filled with the innocence of childhood…”

“It is early 1940s. It is four in the afternoon. The bells at the Bolarum school ring ding-dong for the one last time. Barefooted young boys return home from school, dump their gunnies, wind past lanes and bylanes, before gliding into the Sainikpuri football ground in Ammuguda village, and get into the action of football, with a goalpost fashioning out of two chunks of stones each on either side of the pitch, strewn with sone particles. For the tender-aged boys, football became their only source of enjoyment…”

Ammuguda, with these talented young boys from the poorest homes, became the power house of football in the days to come. It created top footballers who donned the Indian jersey and played for the country in events like the Summer Games and Asian games. This was also the time when the natives were discriminated against and not allowed dignity in social spaces by the British who had their Secunderabad Pub, Garrison Club, and Secunderabad Gymkhana, and the affluent shopping hubs of Oxford Street and James Steet. They too played an elite brand of booted, well-uniformed football, with an elite audience, and the barefooted ‘natives’ only got a chance when the military teams ran short of players.

How Balaram became the best in this pessimistic and unequal scenario, outfoxing the physically strong and well-trained British and other teams with his brilliance on the field is a stuff of folklore. The backdrop of this history lesson on this region and its unfolding in the British-Indian map, how Secunderabad, located on the northern bank of the Hussain Sagar Lake, “grew into a buzzing city with a unique identity”, is documented with academic details in this wonderful book. Indeed, this book is a serious text on the historical, social and political reality of the times, and can be easily listed as a lucidly written ‘sociology of football’ of that era. In that sense, the book is a rare landmark in the ‘sociology of sport’ in India.

“It (Secunderabad) was different from Hyderabad in almost every aspect – from culture, languages, and customs to lifestyle. In Nizam’s Hyderabad, women wore purdah and people spoke Persian and Urdu in general, whereas in Secunderabad, the European way of life was evident throughout. There were clubs, liquor, music, dance, sports, English schools, and churches all over…”

In a special game with seniors in the famous Lallaguda workshop ground, for instance, Balaram became a sudden star. “Balaram, the skinniest of the lot, stood out and destroyed the opposition even though the muscular boys resorted to hard tackling to check on him. He was a distinctive player with mystical skills…”

The workers and the daily-wagers, daily passengers on local trains to their suburban ghettos, became a spontaneous audience, turned him into a spontaneous hero. “Whenever they would see us, they would ask us, when our next match was? Sometimes, they would come back leaving their homebound train to watch us play. They were a hungry lot but never bothered about going back home. After the match they used to check on me whether I am fine or if I need any kind of help,” said Balaram.

“Since then, a bond developed between the subalterns. So much so that whenever Ammuguda Boys would disembark the train, they would recognize the most popular player of the lot, the lithe-frame Balaram. The fans became a strong and recognised symbol for the club…”

In documenting the life and times of Balaram, Sudipta enters the world of national and international football with historical details, forgotten footnotes, social documentary, and magical anecdotes, which he has fished out through his research and documentation of memories. From the banning of barefoot football in1953, to the London Olympics of 1948, when a barefoot India “made France toil hard for a 2-1 win,” the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, their football journeys in Europe, their victory in a practice game against the Metropolitan Police in Surrey for instance, or the victory against Wales, 4-1; and, thereby, into the heady romance of Bengal club football with lakhs of followers and packed stadiums of roaring fans, to particular, high-pitched, tensed-up games where Balaram outshone his opponents and became a darling of his team and the crowd, etc., the book is a treasure-house of lived memories of Indian football.

Such a book is like great cinema. You can see the story unfold in the first imagined homeland in the poor suburbs, to the heady romance of international football, and back to local football’s passionate catharsis. In that sense, football is a game which is truly working class, and magical, like a fascinating film or novel which ends too soon. In Sudipta’s book, Balaram, who turned a recluse in Uttar Para in suburban Kolkata, unknown and forgotten, becomes a brilliant icon of this incomplete magic. An unfinished sentence waiting for a rainbow. A rainbow which shall always glow in the darkest night.

Amit Sengupta is a senior journalist