Many readers may find the title to be paradoxical as it contains the terms ‘Rationalist’ and ‘Muslim’ together. However, one needs to understand that using these paradoxical terms is not a choice but a reflection of our existing contradictions in social interactions. Even though I have achieved a rational mental state through my efforts, I have already been given an identity based on my parent’s religion long before that. In this way, being a rationalist is my achieved mental orientation, while being Muslim is my socially ascribed identity. I wanted to clarify this before opening up the discussion, which will be helpful in contextualizing the issues raised in this article.

The Rajdhani Express departed from Gurgaon Station after starting from New Delhi. My friend, Shruti, sitting across me, began reading a message on her phone regarding the Modi government’s announcement of the implementation of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) starting that day. Being extra cautious in the present politically charged climate, I discreetly cautioned her (in English) against discussing the matter openly on a train. Shruti understood the sensitivity of the situation.

I could also recognize my perceivably over-concern, over which Shruti gave her displeased facial expression. Although she expressed a desire to engage in conversation, she refrained from pressing the issue, likely out of consideration for my concern. My anxiety probably came from being a Muslim man traveling with two girls born in a Hindu family (although one of them was my legal partner and a rationalist herself). Leaving that conversation, we redirected our focus on our four-day exploration of the historical monuments of Delhi with my partner Chandni, an art historian, who guided us through their historical significance.

However, later that night, I could not sleep thinking about my heightened anxieties and the challenges faced by ordinary Muslim citizens in India, in any public place, amidst the prevailing atmosphere of othering and demonization. My mind was jumping over the thoughts around how travelling with my own wife and close friend, carrying non-vegetarian food that I usually eat, discussing something political or controversial in nature, or, just confronting anyone on any issue could trigger any random person or even a policeman against the ‘other’ me.

I contemplated how Muslim men may feel in such shared spaces, precisely like I was feeling. I kept pondering on this question of otherization in a shared space, which then took me into another chain of events that had happened on this trip involving the three of us, which further fueled my introspection regarding equal treatment in the spaces built or developed for our collective use.

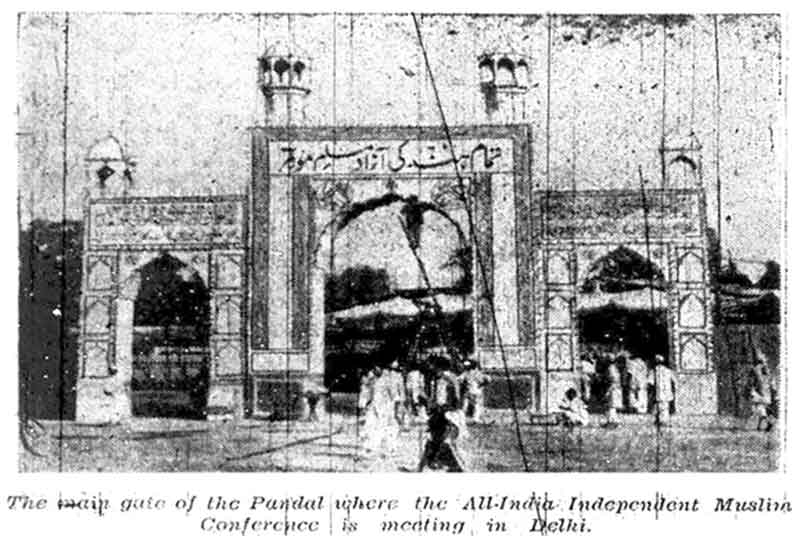

On March 9, our plan was to visit Jama Masjid with the intention of exploring its architecture and its importance in our shared history with Chandni to guide us through it. Despite our enthusiasm, we encountered delays due to heavy traffic at Chauri Bazar in Old Delhi, arriving at the mosque around 7:45 pm. Upon arrival, we were confronted with a disheartening sight: numerous women, sitting on the outer stairs of the mosque, risking their children’s safety in such a densely crowded area. Avoiding the scene, we headed towards one of the main gates, where I entered without any hindrance. However, the gatekeepers harshly stopped Chandni and Shruti, instructing them to leave and pointing to a sign board that clearly mentioned that women are prohibited from entering the mosque after (Maghrib) the evening prayer.

This blatant gender-based discrimination deeply troubled both Chandni and Shruti, as well as myself. Feeling upset, we quickly left the place and found comfort in eating some of the famous non-vegetarian delicacies in the lane opposite the Jama Masjid, temporarily forgetting about the unpleasant experience at the mosque.

Two days later, on March 11, Chandni and I set out to explore Mehrauli. As we wandered through the area, our curiosity led us to an extension of the Mehrauli campus in search of more historical monuments. There, a young man informed us of a nearby dargah. Intrigued by the prospect of visiting the shrine of a Sufi saint revered for his inclusive and liberal philosophy, we followed his directions and discovered the dargah.

However, our initial excitement at finding the shrine quickly disappeared. Upon entering the main building of the Dargah, we encountered a sign prohibiting women from accessing the inner sanctum, primarily an open space where many men were engaged in worship. This sign not only upset me but also challenged my preconceived notion of gender inclusivity in the spaces associated with Sufi saints. Hence, I chose not to enter into the inner, prohibited (for women) area. Feeling disheartened by this revelation, we promptly left the Dargah premises.

I was feeling extremely agitated and frustrated witnessing the direct discrimination against girls and women. It was disheartening for me to see how religious institutions often view females solely through the lens of ‘purity or impurity’. My frustration led me to question why people of faith couldn’t perceive females as curious learners, scholars, guides, or, simply as ordinary human beings seeking knowledge and solace. Chandni seemed to sense my inner turmoil. She suggested we visit another location, namely Khair ul Manzil. We hailed an auto-rickshaw and made our way to the place.

As we stood outside the premises, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of anxiety again, fearing that Chandni might face similar restrictions as before. However, to our relief, we were only required to remove our shoes before entering the mosque area. Chandni was clearly happy and excited when she entered the mosque and walked up to the Mehrab. She then told me all about its history. She revealed that the building was originally a madrasa, commissioned by Maham Anga, Emperor Akbar’s foster mother, specifically for the education of girls and women (as seen in an inscription on its arched entrance). The madrasa played a significant role as it was exclusively run by women Alimas, providing education to females at a time when such opportunities were scarce.

This exemplified the Mughal rulers’ commitment to promoting female education and granting women access to religious spaces they constructed, even during an era when women’s education was not in the popular imagination. Her explanation deeply moved me.

The last four days were profoundly impactful for me, prompting introspection on examples of gender inclusivity and progressive initiatives taken by the Mughal rulers that current Muslim communities and their leaders should ponder upon. The visit also raised pertinent questions about the persistence of discriminatory, unequal, and feudal customs and traditions within religious and Sufi contexts.

Acknowledging the deep roots of the issue, I decided to address this issue directly with the leaders of the Muslim community and religious organizations. While waiting for the train on the platform, I was thinking about the option of protesting or going to court if those concerns were ignored. I recognized the urgency to challenge the patriarchal norms barring access to girls and women to shared spaces and advocate for the reform of cultural practices prevailing in the Muslim community that directly discriminate against them.

However, in mere moments, I was confronted with a familiar anxious situation that an ordinary Muslim man, subject to considerable demonization, may experience in today’s climate. It’s a situation where simply being associated with a Hindu girl, whether as a legal partner or a friend, poses a potentially life-threatening risk. Engaging in politically contentious discussions, similarly, presents a significant risk, as does carrying non-vegetarian food; anything could provoke a policeman to open fire on me, as seen in an unfortunate incident earlier in a running train.

In these challenging times, when the entire Muslim community is evidently going through tremendous fear and facing blatant discrimination by the State and society, speaking against the unfair treatment of women in the male-dominated Muslim community might make many people think I’m against them, even though I strongly support the community against discrimination in today’s anti-Muslim environment. The thoughts generated a feeling in me that it would be ethically wrong to harass a community further which is already struggling for its safety, security, and dignity.

Even though I was deeply hurt by seeing what happened with girls and women in those religious places as a result of the patriarchal systems prevailing in the Muslim community (which exist in other communities, too), I chose not to plan a protest or go to court.

Eventually, I experienced restlessness through the night, torn between expressing solidarity with my partner and friend and avoiding any actions that might further contribute to the harassment of the ‘conditioned’ Muslim men. In grappling with this dilemma and accompanying anxiety, I am writing these thoughts as a gesture of solidarity with Chandni, Shruti, and every woman who was forced to sit outside the Jama Masjid and the dargah in Delhi, and all Muslim men who feel unsafe in public spaces.

This effort aims to advocate for the cause of all women across all communities, and Muslim men, which, fundamentally, is the cause of humanity. Indeed, this is driven by the hope of eventual liberation, where every individual can enjoy unrestricted access to public and all kinds of shared spaces, and discuss and debate openly about all sorts of things without fear.

By composing these notes, I am committing myself to initiating constructive, peaceful dialogues with the leaders of the Muslim community concerning this matter, no matter how long it might take to resolve. However, I am wondering whether I will ever be welcomed for an engagement by certain leaders of the Hindu community, who instigate anti-Muslim sentiments and demonize Muslim citizens on a daily basis

Dr Ajazuddin Shaikh is Research Associate, Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Ahmedabad, and a civil society activist.