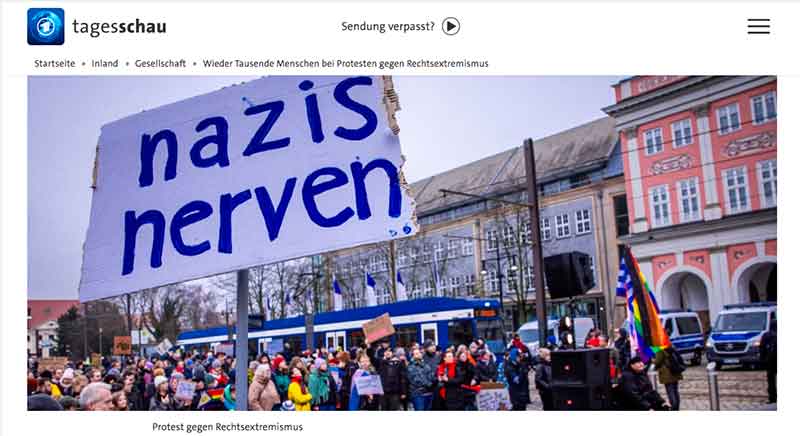

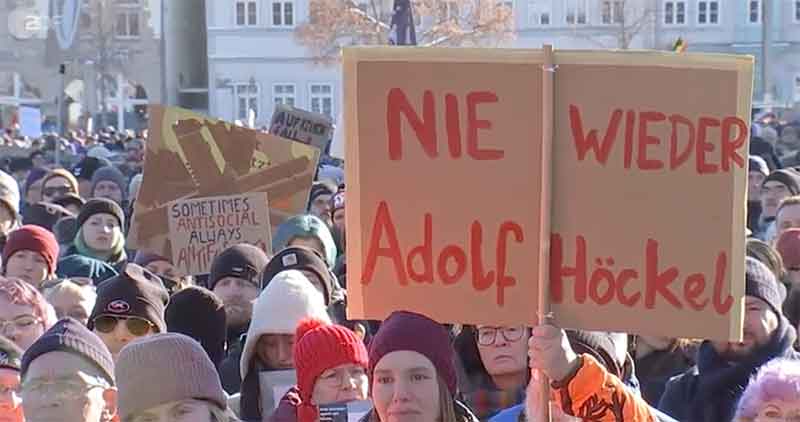

Hamburg. Sunday lunchtime, 1 pm. Once again, tens of thousands of people gather in the north with a sea of colourful flags and self-painted posters to demonstrate against fascism and the AfD in particular. It is moving to watch the images of the last few weeks. In no other country where right-wing populists are currently on the rise or already in power has there been such widespread resistance from the population. The silent majority is rising up. “Thank God!”, one might say and believe that the rise of the radical right can still be stopped. But what follows the demonstrations? What happens later in the evening when everyone is back at home on the sofa in the warmth?

One of the speakers on Edmund-Siemers Allee this afternoon is the political economist and transformation researcher Maja Göpel. She appeals to politicians in office to remember the importance of their oath and the promise of justice it contains. She calls on those with economic power to commit to our common values and to Germany as a business location. On the other hand, she invites people who have lost faith in the established parties to row back from the right-wing fringe and re-enter into dialogue with “us”. It is also an appeal to return to the essentials in a public discourse that seems to have lost itself in the smoke and mirrors of right-wing populism. The speech aptly summarises the core issues of our present society. In addition to demonstrations and loud dissent, we must achieve one thing above all: We have to set in motion a social development that can halt the process of the decomposition of democracy which is going on.

So let’s rewind the film for a moment and look for the causes.

“Mr Gorbachev tear down that wall”. Actually, not everything, but perhaps a lot of things began with this one famous sentence. And no, I’m not suggesting that the fall of the Berlin Wall and the integration of the eastern states that came with it are the cause of the problem. But if you look at the current party landscape, one thing is particularly striking: The Left is missing. I’m not referring to the party that is nevertheless shedding a striking light on this aspect these days. I mean what the so-called left-wing politics once stood for. While the remnants of the left-wing party landscape are currently dismantling themselves, a phenomenon is also clearly emerging: the only ones questioning “the system” – albeit with crude and dishonest logic – are the right-wingers.

Back to Gorbachev. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, the idea of socialism and the associated belief in a better world crumbled to dust. Until then, there had been a struggle for the “right” economic system, fought out in a global battle: communism versus capitalism. At the same time, the idea of communism always stood for denouncing and wanting to eliminate social injustices. Communists together with the oppressed, exploited and worse-off in the world. Now, the despots of socialism seem to have buried the demand for social justice with them, as from then on there was no longer any Marx, Che Guevara or Lenin to assemble behind in unity. So these movements faded away in all directions, but the inequality in the world remained. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, the world freed itself from socialism once and for all. But quietly and secretly, the idea of justice was also deserted. While the gap between rich and poor continued to widen since the turn of the millennium, and the world celebrated the now seemingly limitless free trade in a dancing frenzy, the oppressed and exploited remained oppressed and exploited, but today they are called the “left behind”. This term alone is so characteristic of the current zeitgeist: someone who is left behind is someone who is too slow, who has not worked hard enough. Welcome to the new world.

The turn of the millennium was followed several financial crises shortly after, that threatened to shake the system. These crises were fought on the backs of the general public. Today, Maja Göpel rightly recalls how debts were distributed to the general public during the financial crisis, while the profits remained in the hands of a few individuals. The financial crisis was followed by the euro crisis – almost as an inevitable aftershock – which followed the same logic. This time in particular at the expense of the poorer European states. The belief in justice began to show serious cracks. In her book, Franziska Schreiber, former chairwoman of JA Sachsen (youth organisation of the AfD), describes how criticising the euro policy brought her to the AfD in 2013. One may not share her views and conclusions. Nonetheless justified criticism was entirely appropriate at the time. But there was no outcry from the righteous.

No, this is not a vituperative criticism of the left – May it rest in peace! This is a wake-up call to all moderate democrats who once set out to save the world and to those who once took up the cause of “social justice”. Where is the criticism of the system? This is a wake-up call to all those who stand up for democracy in their deepest convictions.

Since the end of the 1990s, the social issue has been shamefully neglected in this country. Today, it can only be found as a side note in various reform plans. It is important to understand one thing: Social justice and democracy are aspects of our statehood that are mutually dependent. There is a solid reason why the Parliamentary Council established this country as a social and democratic constitutional state, because without social justice, democracy cannot exist. But this is precisely the development in which we find ourselves today, our eyes widening in horror.

Democracy contains an elementary promise: We are all equal! Because we are all equal, we can all vote and be elected. Because we are all equal, some cannot rule over others and because we are all equal, we all have the same right to participate. But when economic conditions and developments give the lie to this promise, democracy crumbles. The loss of prosperity or the impending decline of the middle class can shake confidence in democracy. Economic experts have been pointing out for years that the middle class in Germany is crumbling. According to a 2021 study by the Bertelsmann Foundation, young adults are particularly affected by the disintegration of the middle class, 20% of whom have fallen into the lower social strata. At the same time, it is becoming increasingly difficult to move up into the middle class at all. A high level of education is important in order to belong to it at all, but at the same time people in eastern Germany are less likely to reach the middle income bracket at all. The study only looks at income levels and ignores shifts in wealth and consumption-based factors, such as the ability to buy a house or car. This study has not yet factored in the developments of the last few years, which have seen hefty inflation that has affected people in the lower and middle income brackets specifically.

While the lower classes have often completely turned their backs on politics, the middle class is still politically active. However, this middle class, the well-educated with a stable income, is highly frustrated. Far too often, it is told that the AfD voters are made up of the “left behind”, the less educated and the social precariat. However, the figures do not bear this out: in 2021, only just under 18% of AfD voters belonged to this group. The remaining 80% essentially belong to the middle class. It is those with a comparatively high level of political education and engagement who are currently turning away from the “established parties”. Not all of them are turning to the right-wing camp though: there is currently a veritable flood of newly founded parties.

In addition to the loss of faith in equality as a promise of democracy, it must be recognised that economic and political equality are mutually dependent. Those with less wealth and income often also have less influence, less representation of interests and less access to political (honorary) positions and decision-making processes.

If we want to save democracy, we should argue and demonstrate, without question. Above all, however, we must address the trenches of social inequality; dare to be more courageous in criticising the system. But perhaps it would be enough if we were simply to return to a principle of our statehood that we carried with pride in the 1990s, but then seemingly forgot in the last millennium: The principle of the social market economy. It’s still the economy (that’s) stupid!

Mariam K is a research scholar on International Law at Hamburg University.