by Thomas Klikauer and Danny Antonelli

Zone of Interest is a film that every German child should be shown at the age of 15. Yes, they will not understand why the screen is black for so long at the beginning, and they might get a little restless because there are no chase scenes.

But the longer they watch, the more they will start to understand exactly what Hannah Arendt meant by “Adolf Eichmann and the banality of evil.”

Martin Amis wrote a novel that has the same title as the film, but apart from the title and the location, Jonathan Glazer has managed to tell a story that stands on its own and is more powerful than the one informing the plot of the Amis novel.

No spoilers here for people who want to read the novel. The novel depicts a love story in the shadow of Auschwitz. The film doesn’t. Not by a long shot.

The film is in German. Jonathan Glazer, the director, doesn’t speak or read German. He had to trust his actors and the script translators to bring across the dialogue in such a way that it made sense to the viewer. For those of us who understand German, the dialogue is superb.

The set magnificent. The costumes perfectly in tune with the time. No Hollywood over-dressing, no star-friendly makeup or hairdressing. Just normal people in a normal setting. Except of course, it’s Auschwitz.

Yes, the film has English subtitles for the American and British markets. Too bad. Because they were embedded in the copy of the film that I saw, they were sometimes a distraction.

But they were small enough to not be a major distraction. And, as all subtitles, they are only accurate to a point. Subtleties of meaning and turns of phrase that are akin to idioms function differently in every language.

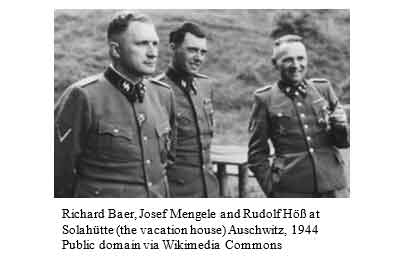

Christian Friedel, who played a photographer for the Berlin police department in the hit series Babylon Berlin, is absolutely believable as the German Nazi commandant Rudolf Höss. No Hollywood over-acting, no “I’m the bad guy” posturing. Höss (the historical personage) was the commandant of the Auschwitz death camp. He knew what he was doing there, and he knew his job was to exterminate Jews.

Friedel who, like Höss, sports what is known today as a Hitler-Youth haircut, shows us an efficient camp commander who has to jockey to keep his post by using his political connections in Berlin.

Nothing different from the vicissitudes of a manager heading a branch – an important branch – of a major corporation. His job is to make the camp run smoothly, which means the killing has to be done efficiently and cost-effectively.

His meeting with the designers of a new rotating oven system for the burning of corpses is no different from a meeting a manager would hold who needs to order new production facilities.

“The optimal position for a business is to be both effective and efficient, whereby the right goals are pursued and the organization is being run in a cost-efficient manner.”

Friedel, who plays Höss as one would play a senior manager who has the desire to control, and also the will to indulge himself in the pleasures of life – horses, prostitutes, flowers, lilac trees – is trying to be both effective and efficient. He’s running a business for the corporation.

The corporate entity is the NSDAP, with Adolf Hitler at the helm. The main product is Death. Not indiscriminate death; this death is aimed specifically at Jews and other undesirables, as laid out in the corporate guidelines written by important members of the board of directors, like Himmler, Goering, Goebbels and of course the CEO and Chairman of the Board Adolf Hitler.

These corporate guidelines – aka The Final Solution – were handed down to managers like Höss. He made sure the SS men and soldiers under his command carried them out faithfully.

Sandra Hüller, who has won the European Film Award for Best Actress, plays Hedwig, the venal wife of the camp commandant. Like her husband Rudolf, she came from humble beginnings and is now living “the ideal National Socialist life” in the extended Reich (empire) that Hitler has created for the benefit of “normal” Germans like her.

When her husband is ordered from above to transfer to Berlin to take up what is actually a more important post, her lifestyle is threatened and she urges her husband to put up a fight against the political actors who have caused this upsetting situation.

If not able to stop the transfer then to at least make sure that the house where she and her children are living is not given to the new commander who is to replace Rudolf.

We don’t see any killings. We don’t see any torture. The only scary moment for Höss and his children is, –while he and his kids are bathing in the river – when he finds human remains. That gets him out of the water fast, and he scoops up his children and runs back home with them.

And what a lovely home it is. A three-story house with heating installed to fend off the snowy winters. A backyard with green grass, a small swimming pool for the kids, with a slide, a gazebo where Hedwig and her lady visitors can sit and sip tea, and flowers, flowers, everywhere.

The most beautiful flowers you can imagine. Red, white, and the very special golden yellow Mädchenaugen. Coreopsis. Girl’s eyes. Beautiful two-tone flowers with a protruding brown-maroon heart. This makes the flowers resemble the iris and pupils of a girl’s eyes.

Only if you have no sense of irony can a description of that flower have no effect on you. As when Hedwig puts a bunch of sheer petticoats on the table and instructs her Polish servant girls to “take only one,” while she goes to her bedroom and unwraps a full length brown mink coat, tries it on, and studies herself in the mirror while wrapping it around her like the models do in advertisement photos.

Later, when chatting with her lady neighbors – wives of other camp officers – they gossip about an overweight woman who picked a dress which had been worn by a Jewess half her size and didn’t fit properly, but she insisted in having it anyway because she “loved” it and was going to go on a diet in order to be able to fit into it properly.

And then Hedwig shows her Kaffee Klatsch girlfriends a diamond ring. “Guess where I found it? In the toothpaste.” They laugh and comment “How clever,” and “Yes, they are clever.” Then Hedwig tells them that she has ordered more tubes of toothpaste.

In German there is a word that describes these women: gierig. The official translation is “greedy.” But what they display is the same as what a kid who has hardly ever tasted chocolate displays when he is taken to a chocolate shop for the first time and told he can choose whatever he likes, but not too much.

His mouth waters because he’d love to eat every single piece of chocolate in the shop, but he knows he can’t, so he acts shy and chooses the 2 or 3 pieces that look delicious and he can savor later.

These women are hungry for the luxury items their captives brought with them to the camp. They are thirsty for the recognition they will get from their neighbors when they show off their pillaged dresses and rings and fur coats. And they are proud of their standing, as the wives of officers who are high enough up in the ranks to be able to “afford” to treat their women to these little trinkets.

Meanwhile Hedwig and Rudolf’s children play at night in bed with the gold fillings from extracted teeth.

Do you understand now what is meant by the banality of evil?

While all these scenes of what could pass for a normal domestic life play out in front of us, right there, at the back of the splendidly flowered garden is the gray cement wall of the camp, with a roll of barbed wire at the top.

The soundscape, which remains well in the background is punctuated from time to time by distant gunshots, the occasional shouted order, a muted scream before a gunshot ends it.

The constant rumble of the crematorium is also muted. That’s the production line working 24/7 to make sure that deadlines [pun intended] are met and orders are fulfilled. From time to time we see clouds of dark smoke emanate from the towers where the bodies are being turned into ash that will then serve as fertilizer for the garden.

Höss is an excellent manager and his skills are finally recognized by the powers that be. He is reassigned as the head of Auschwitz in order to manage the new big job that only he can take care of so efficiently:

700,000 Jews from Hungary must be disposed of urgently, and a contingent of them must be pared off as slave labor for the commanders who need them. Höss is the man who can deliver.

If you are 15 years old and you see this film, it might take you a while to fully grasp its significance. But, as time goes by and you see the world around you in a clearer light, you will begin to realize that you are surrounded by people who will grasp at any opportunity to get more out of life than they have now.

And these are your neighbors. These are people you grew up with. These are the “normal” people who are able, like the Trumpista neofascists of today, to live with the cognitive dissonance of the death camp that borders the backyard as long as their private “Gier” is being satisfied.

Born on the foothills of Castle Frankenstein, Thomas Klikauer is the author of over 950 publications including a book on Alternative für Deutschland: The AfD – published by Liverpool University Press.

Danny Antonelli grew up in the USA, now lives in Hamburg, Germany and writes radio plays, stories and is a professional lyricist and librettist.