1 Sanctions as collective punishment

Under the Fourth Geneva Convention, collective punishment is war crime. Article 33 states that “No protected person may be punished for an offense that he or she did not personally commit.” At present, we treat nations as though they were persons: We punish entire nations by sanctions, even when only the leaders are guilty, even though the burdens of the sanctions fall most heavily on the poorest and least guilty of the citizens, and even though sanctions often have the effect of uniting the citizens of a country behind the guilty leaders. Should we not regard sanctions as collective punishment?

If we do so, then sanctions are a war crime, under the Fourth Geneva Convention. There is much that can be criticized in the way that the Gulf War of 1990-1991 was carried out. Besides military targets, the US and its allies bombed electrical generation facilities with the aim of creating postwar leverage over Iraq.

The electrical generating plants would have to be rebuilt with the help of foreign technical assistance, and this help could be traded for postwar compliance. In the meantime, hospitals and water-purification plants were without electricity. Also, during the Gulf War, a large number of projectiles made of depleted uranium were fired by allied planes and tanks. The result was a sharp increase in cancer in Iraq. Finally, both Shi’ites and Kurds were encouraged by the Allies to rebel against Saddam Hussein’s government, but were later abandoned by the allies and slaughtered by Saddam. The most terrible misuse of power, however, was the US and UK insistence the sanctions against Iraq should remain in place after the end of the Gulf War. These two countries used their veto power in the Security Council to prevent the removal of the sanctions.

Their motive seems to have been the hope that the economic and psychological impact would provoke the Iraqi people to revolt against Saddam. However that brutal dictator remained firmly in place, supported by universal fear of his police and by massive propaganda. The effect of the sanctions was to produce more than half a million deaths of children under five years of age, as is documented by UNICEF data. The total number of deaths that the sanctions produced among Iraqi civilians probably exceeded a million, if older children and adults are included.

Ramsey Clark, who studied the effects of the sanctions in Iraq from 1991 onwards, wrote to the Security Council that most of the deaths “are from the effects of malnutrition including marasmas and kwashiorkor, wasting or emaciation which has reached twelve per cent of all children, stunted growth which affects twenty-eight per cent, diarrhea, dehydration from bad water or food, which is ordinarily easily controlled and cured, common communicable diseases preventable by vaccinations, and epidemics from deteriorating sanitary conditions. There are no deaths crueler than these.

They are suffering slowly, helplessly, without simple remedial medication, without simple sedation to relieve pain, without mercy.” The sanctions that are currently being imposed on Iran are also an example of collective punishment. They are damaging the health of ordinary Iranian citizens, who can in no way be blamed fro the policies of their government. According to Wikipedia: “Pharmaceuticals and medical equipment do not fall under the international sanctions, but the country is facing shortages of drugs for the treatment of 30 illnesses, including cancer, heart and breathing problems, thalassemia and multiple sclerosis, because Iran is not allowed to use International payment systems…. In addition, there are 40,000 hemophiliacs who can’t get anti-clotting medicines… An estimated 23,000 Iranians with HIV/Aids have had their access to the drugs they need to keep alive severely restricted.” In addition to the fact that sanctions are a form of collective punishment, and thus a war crime under the Fourth Geneva Convention, we should also remember that Iran is completely within its rights under international law and under the NPT.

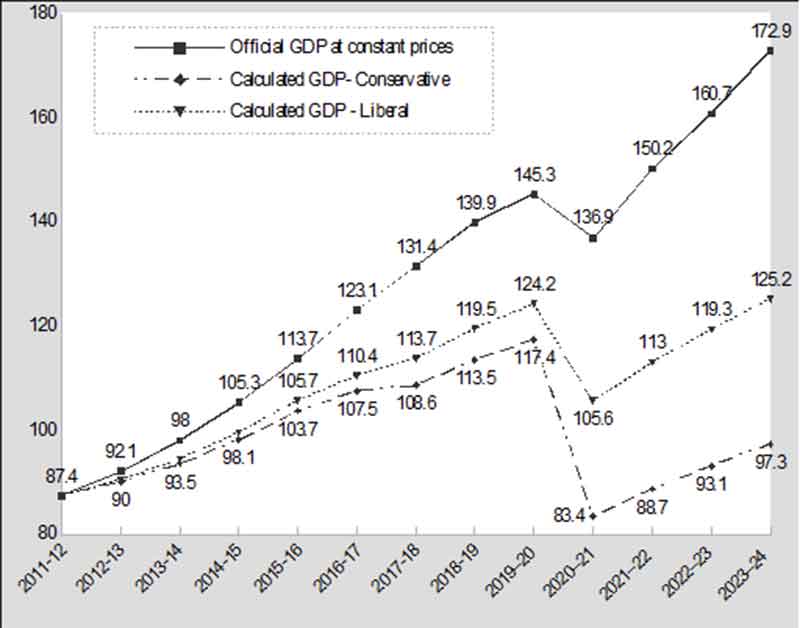

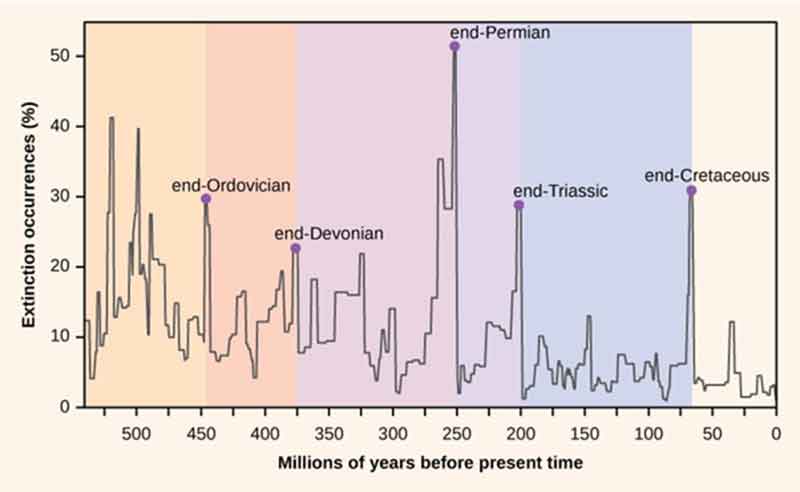

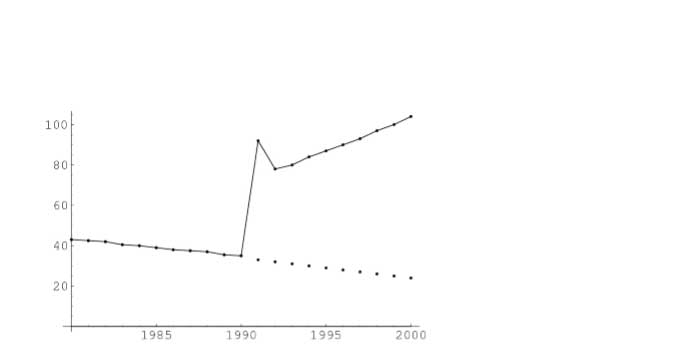

Figure 1: Deaths of children under five years of age in Iraq, measured in thousands. This graph is based on a study by UNICEF, and it shows the effect of sanctions on child mortality. From UNICEF’s figures it can be seen that the sanctions imposed on Iraq caused the deaths of more than half a million children.

2 Israel, Iran and the NPT

The NPT was designed to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons beyond the five nations that already had them; to provide assurance that “peaceful” nuclear activities of nonnuclear-weapon states would not be used to produce such weapons; to promote peaceful use of nuclear energy to the greatest extent consistent with non-proliferation of nuclear weapons; and finally, to ensure that definite steps towards complete nuclear disarmament would be taken by all states, as well steps towards comprehensive control of conventional armaments (Article VI). The non-nuclear-weapon states insisted that Article VI be included in the treaty as a price for giving up their own ambitions.

The full text of Article VI is as follows: “Each of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a Treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict international control.” Several nuclear weapon states, notably the United States, are grossly violating Article VI. The NPT has now been signed by 187 countries and has been in force as international law since 1970.

However, Israel, India, Pakistan, and Cuba have refused to sign, and North Korea, after signing the treaty, withdrew from it in 1993. According to Wikipedia, Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion was “nearly obsessed with obtaining nuclear weapons”, and under his administration, work on obtaining these weapons for Israel was started in 1949 under his administration.

The Wikipedia article states that “In 1949 Israeli scientists were invited to the Saclay Nuclear Research Centre, this cooperation leading to a joint effort including sharing of knowledge between French and Israeli scientists especially those with knowledge from the Manhattan Project… Progress in nuclear science and technology in France and Israel remained closely linked throughout the early fifties….

There were several Israeli observers at the French nuclear tests and the Israelis had unrestricted access to French nuclear test explosion data. The article continues: “When Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, France proposed Israel attack Egypt and invade the Sinai as a pretext for France and Britain to invade Egypt posing as ‘peacekeepers’ with the true intent of seizing the Suez Canal. In exchange, France would provide the nuclear reactor as the basis for the Israeli nuclear weapons program. Shimon Perez, sensing the opportunity on the nuclear reactor, accepted.”

According to Wikipedia, “Top secret British documents obtained by BBC Newsnight show that Britain made hundreds of secret shipments of restricted materials to Israel in the 1950s and 1960s. These included specialist chemicals for reprocessing and samples of fissile material, uranium-235, in 1959, and plutonium in 1966, as well as highly enriched lithium-6, which is used to boost fission bombs and fuel hydrogen bombs. The investigation also showed that Britain shipped 20 tons of heavy water directly to Israel in 1959 and 1960 to start up the Dimona reactor.”

Here we see both France and Britain as gross violators of the NPT, since the NPT forbids nations possessing nuclear weapons helping other nations to obtain them. The United States government knew what was happening, but prevented the knowledge from becoming public. Israel completed its first nuclear weapons in the early 1960’s. The country is now thought to have 100 to 300 of them, including hydrogen bombs and neutron bombs. Israel’s government maintains a policy of “nuclear opacity”, meaning that while visibly possessing nuclear weapons, it denies having them.

3 Recent sanctions against Iran

In a November 6 article in the Internet journal Countercurrents, Medea Benjamin wrote: “Iranian government officials want to know how the Trump administration can get away with punishing Iran and other countries for complying with the internationally recognized nuclear deal signed in 2015.

‘The US is, in effect, threatening states who seek to abide by Resolution 2231 with punitive measures,’ said President Rouhani. ‘This constitutes a mockery of international decisions and the blackmailing of responsible parties who seek to uphold them.’… “This is the second round of sanctions since Trump pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal, a deal that was signed in 2015 not only by the US and Iran, but also by Germany, England, France, Russia and China – and approved unanimously by the UN Security Council. It’s also a deal that has been working. Iran has been complying with the most intrusive inspections regime ever devised, as the International Atomic Energy Agency has confirmed 13 times. “Trump, always ready to bulldoze international agreements, unilaterally withdrew from the deal and imposed a first round of sanctions in August and the second round now.

These sanctions are designed to stop not just US companies from trading with Iran, but all companies – anywhere in the world. According to Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, ‘Any financial institution, company, or individual who evades our sanctions risks losing access to the U.S. financial system and the ability to do business with the United States or U.S. companies.’ In effect, the Trump administration, practicing imperial hubris on steroids, is determined to punish countries abiding by an internationally approved agreement.” The sanctions are already taking a tragic toll on the innocent people of Iran, undermining both their health and their economic security. Surely this must be seen as an example of collective punishment.

Mordechai Vanunu, whistleblower and martyr

Mordechai Vanunu was working as a technician at the Israeli reactor installation Dimona, where he observed work on the construction nuclear weapons. As he thought more and more about what he was doing, his conscience began to bother him.

In 1986, on a trip to England, he told the British press what he knew about the Israeli nuclear weapons program. The government of Israel was furious, and arranged a classical “honey trap” in which a female agent of Mossad used sex to lure Vanunu to Italy, where he was drugged and kidnapped. The drugged prisoner was transported to Israel and tried for treason. In fact one of Vanunu’s motives had been to save his country from destruction in a nuclear war. Whistleblowers are often the best patriots.

Vanunu spent 18 years in prison, the first 11 of which were in solitary confinement. Released in 2004, he thought that he would be free to leave the country, but he was soon re-arrested. Today, he is free to move within Israel but his movements and contacts are severely restricted. Vanunu is often considered to be a prisoner of conscience similar to Nelson Mandela, Chelsea Manning, Julian Assange and Edward Snowdon. The fact that Israel has an apartheid system even worse than the one that formerly oppressed South Africa strengthens the the similarity between Vanunu and Mandela.

4 Attacks on Iran, past and present

Iran has an ancient and beautiful civilization, which dates back to 7,000 BC, when the city of Susa was founded. Some of the earliest writing that we know of, dating from from approximately 3,000 BC, was used by the Elamite civilization near to Susa. Today’s Iranians are highly intelligent and cul- tured, and famous for their hospitality, generosity and kindness to strangers.

Over the centuries, Iranians have made many contributions to science, art and literature, and for hundreds of years they have not attacked any of their neighbors. Nevertheless, for the last 90 years, they have been the victims of foreign attacks and interventions, most of which have been closely related to Iran’s oil and gas resources. The first of these took place in the period 1921-1925, when a British-sponsored coup overthrew the Qajar dynasty and replaced it by Reza Shah. Reza Shah (1878-1944) started his career as Reza Khan, an army officer. Because of his high intelligence he quickly rose to become commander of the Tabriz Brigade of the Persian Cossacks. In 1921, General Edmond Ironside, who commanded a British force of 6,000 men fighting against the Bolshe- viks in northern Persia, masterminded a coup (financed by Britain) in which Reza Khan lead 15,000 Cossacks towards the capital.

He overthrew the gov- ernment, and became minister of war. The British government backed this coup because it believed that a strong leader was needed in Iran to resist the Bolsheviks. In 1923, Reza Khan overthrew the Qajar Dynasty, and in 1925 he was crowned as Reza Shah, adopting the name Pahlavi. Reza Shah believed that he had a mission to modernize Iran, in much the same way that Kamil Ata Turk had modernized Turkey. During his 16 years of rule in Iran, many roads were built, the Trans-Iranian Railway was constructed, many Iranians were sent to study in the West, the University of Tehran was opened, and the first steps towards industrialization were taken. However, Reza Shahs methods were sometimes very harsh. In 1941, while Germany invaded Russia, Iran remained neutral, perhaps leaning a little towards the side of Germany. However, Reza Shah was suf- ficiently critical of Hitler to offer safety in Iran to refugees from the Nazis.

Fearing that the Germans would gain control of the Abadan oil fields, and wishing to use the Trans-Iranian Railway to bring supplies to Russia, Britain invaded Iran from the south on August 25, 1941. Simultaneously, a Russian force invaded the country from the north. Reza Shah appealed to Roosevelt for help, citing Iran’s neutrality, but to no avail. On September 17, 1941, he was forced into exile, and replaced by his son, Crown Prince Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. Both Britain and Russia promised to withdraw from Iran as soon as the war was over. During the remainder of World War II, although the new Shah was nominally the ruler of Iran, the country was governed by the allied occupation forces.

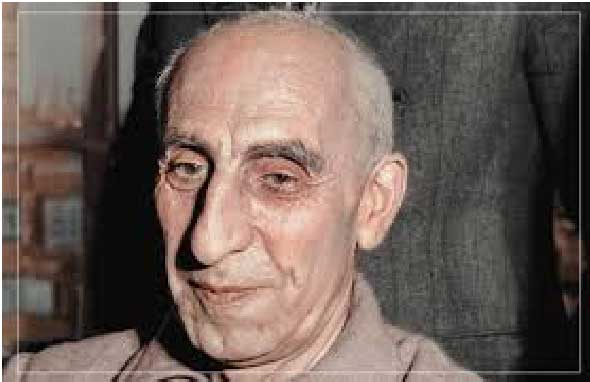

Figure 2: In 1951, Mohammad Mosaddegh became Prime Minister of Iran through democratic elections. He was from a highly-placed family and could trace his ancestry back to the shahs of the Qajar dynasty. Among the many reforms made by Mosaddegh was the nationalization of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s possessions in Iran. The British asked US President Eisenhower and the CIA to join M16 in carrying out a coup, claiming that Mosaddegh represented a communist threat (a ludicrous argument, considering Mosaddegh’s aristocratic background).

Reza Shah, had a strong sense of mission, and felt that it was his duty to modernize Iran. He passed on this sense of mission to his son, the young Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi . The painful problem of poverty was every- where apparent, and both Reza Shah and his son saw modernization of Iran as the only way to end poverty. In 1951, Mohammad Mosaddegh became Prime Minister of Iran through democratic elections. He was from a highly-placed family and could trace his ancestry back to the shahs of the Qajar dynasty.

Among the many re- forms made by Mosaddegh was the nationalization of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s possessions in Iran. Because of this, the AIOC (which later became British Petroleum), persuaded the British government to sponsor a secret coup that would overthrow Mosaddegh. The British asked US President Eisenhower and the CIA to join M16 in carrying out the coup, claiming that Mosaddegh represented a communist threat (a ludicrous argument, considering Mosaddegh’s aristocratic background). Eisenhower agreed to help Britain in carrying out the coup, and it took place in 1953. The Shah thus obtained complete power over Iran. The goal of modernizing Iran and ending poverty was adopted as an almost-sacred mission by the young Shah, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, and it was the motive behind his White Revolution in 1963, when much of the land belonging to the feudal landowners and the crown was distributed to land- less villagers.

However, the White Revolution angered both the traditional landowning class and the clergy, and it created fierce opposition. In dealing with this opposition, the Shahs methods were very harsh, just as his fathers had been. Because of alienation produced by his harsh methods, and because of the growing power of his opponents, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi was overthrown in the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The revolution of 1979 was to some extent caused by the BritishAmerican coup of 1953. One can also say that the westernization, at which both Shah Reza and his son aimed, produced an anti-western reaction among the conservative elements of Iranian society. Iran was “falling between two stools”, on the one hand western culture and on the other hand the country’s traditional culture. It seemed to be halfway between, belonging to neither. Finally in 1979 the Islamic clergy triumphed and Iran chose tradition.

Meanwhile, in 1963, the US had secretly backed a military coup in Iraq that brought Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath Party to power. In 1979, when the western-backed Shah of Iran was overthrown, the United States regarded the fundamentalist Shiite regime that replaced him as a threat to supplies of oil from Saudi Arabia. Washington saw Saddam’s Iraq as a bulwark against the Shiite government of Iran that was thought to be threatening oil supplies from pro-American states such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. In 1980, encouraged to do so by the fact that Iran had lost its US backing, Saddam Hussein’s government attacked Iran. This was the start of an extremely bloody and destructive war that lasted for eight years, inflicting almost a million casualties on the two nations. Iraq used both mustard gas and the nerve gases Tabun and Sarin against Iran, in violation of the Geneva Protocol.

Both the United States and Britain helped Saddam Hussein’s government to obtain chemical weapons. The present attacks on Iran by Israel and the United States, both actual and threatened, have some similarity to the war against Iraq, which was launched by the United States in 2003. In 2003, the attack was nominally motivated by the threat that nuclear weapons would be developed, but the real motive had more to do with a desire to control and exploit the petroleum resources of Iraq, and with Israel’s extreme nervousness at having a powerful and somewhat hostile neighbor. Similarly, hegemony over the huge oil and gas reserves of Iran can be seen as one the main reasons why the United States is presently demonizing Iran, and this is combined with Israel’s almost paranoid fear of a large and powerful Iran. Looking back on the “successful” 1953 coup against Mosaddegh, Israel and the United States perhaps feel that sanctions, threats, murders and other pressures can cause a regime change that will bring a more compliant government to power in Iran – a government that will accept US hegemony. But aggressive rhetoric, threats and provocations can escalate into full-scale war. I do not wish to say that Iran’s present government is without serious faults.

However, any use of violence against Iran would be both insane and criminal. Why insane? Because the present economy of the US and the world cannot support another large-scale conflict; because the Middle East is already a deeply troubled region; and because it is impossible to predict the extent of a war which, if once started, might develop into World War III, given the fact that Iran is closely allied with both Russia and China. Why criminal? Because such violence would violate both the UN Charter and the Nuremberg Principles. There is no hope at all for the future unless we work for a peaceful world, governed by international law, rather than a fearful world, where brutal power holds sway.

5 An attack on Iran could escalate

Despite the willingness of Iran’s new President, Hassan Rouhani to make all reasonable concessions to US demands, Israeli pressure groups in Washington continue to demand an attack on Iran. But such an attack might escalate into a global nuclear war, with catastrophic consequences.

As we approach the 100th anniversary World War I, we should remember that this colossal disaster escalated uncontrollably from what was intended to be a minor conflict. There is a danger that an attack on Iran would escalate into a large-scale war in the Middle East, entirely destabilizing a region that is already deep in problems. The unstable government of Pakistan might be overthrown, and the revolutionary Pakistani government might enter the war on the side of Iran, thus introducing nuclear weapons into the conflict. Russia and China, firm allies of Iran, might also be drawn into a general war in the Middle East. Since much of the world’s oil comes from the region, such a war would certainly cause the price of oil to reach unheard-of heights, with catastrophic effects on the global economy.

In the dangerous situation that could potentially result from an attack on Iran, there is a risk that nuclear weapons would be used, either intentionally, or by accident or miscalculation. Recent research has shown that besides making large areas of the world uninhabitable through long-lasting radioactive contamination, a nuclear war would damage global agriculture to such a extent that a global famine of previously unknown proportions would result. Thus, nuclear war is the ultimate ecological catastrophe. It could destroy human civilization and much of the biosphere. To risk such a war would be an unforgivable offense against the lives and future of all the peoples of the world, US citizens included.

To accept money from agents of a foreign power to perform actions that put one’s own country in danger is, by definition, an act of treason. Why are members of the US Senate and House of Representatives, who demonstrably have accepted money from agents of a foreign power, the State of Israel, not accused of treason when they are bribed to take actions that put their country in danger? If members of the US government should vote for an attack on Iran, they would be traitors not only to the United States, but to all of humanity, and indeed traitors to all living things. Possibly as early as this autumn, Israel may start a large-scale war in the Middle East and elsewhere by bombing Iran.

The consequences are unforeseeable, but there are several ways in which the conflict could escalate into a nuclear war, particularly if the US supports the Israeli attack, and if Pakistan, Russia and China become involved. Why is the threat especially worrying? Because of the massive buildup of U.S. naval forces in the Persian Gulf. Because of Netanyahu’s government’s stated intention to attack Iran, despite opposition from the people of Israel. Because of President Obama’s declarations of unconditional support for Israel; and because Pakistan, a nuclear power, would probably enter the war on the side of Iran. Most probably, a military attack on Iran by Israel would provoke an Iranian missile attack on Tel Aviv, and Iran might also close the Strait of Hormuz. The probable response of the U.S. would be to bomb Iranian targets, such as shore installations on the Persian Gulf. That might well provoke Iran to sink one or more U.S. ships by means of rockets, and if that should happen, the U.S. public would demand massive retaliation against Iran. Meanwhile, in Pakistan, the unpopularity of the U.S.-Israel alliance, as well as the memory of numerous atrocities, might lead to the overthrow of Pakistan’s less-than-stable government.

Israels response might be a preemptive nuclear attack on Pakistan’s nuclear installations. One reads that Russia has already prepared for the conflict by massing troops and armaments in Armenia, and China may also be drawn into the conflict. In this tense situation, there would be a danger that a much larger nuclear exchange could occur because of a systems failure or because of an error of judgement by a military or political leader. A thermonuclear war would be the ultimate environmental disaster.

Recent research has shown that thick clouds of smoke from firestorms in burning cities would rise to the stratosphere, where they would spread globally and remain for a decade, blocking the hydrological cycle, and destroying the ozone layer. A decade of greatly lowered temperatures would also follow. Global agriculture would be destroyed. Human, plant and animal populations would perish. We must also consider the very long-lasting effects of radioactive contamination.

One can gain a small idea of what it would be like by thinking of the radioactive contamation that has made large areas near to Chernobyl and Fukushima permanently uninhabitable, or the testing of hydrogen bombs in the Pacific in the 1950’s, which continues to cause leukemia and birth defects in the Marshall Islands more than half a century later. In the event of a thermonuclear war, the contamination would be enormously greater. We have to remember that the total explosive power of the nuclear weapons in the world today is 500,000 times as great as the power of the bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. What is threatened today is the complete breakdown of human civilization and the destruction of much of the biosphere. The common human culture that we all share is a treasure to be carefully protected and handed down to our children and grandchildren. The beautiful earth, with its enormous richness of plant and animal life, is also a treasure, almost beyond our power to measure or express. What enormous arrogance and blasphemy it is for our leaders to think of risking these in a thermonuclear war!

6 The agony of Iraq

There is a close relationship between petroleum and war. James A. Paul, Executive Director of the Global Policy Forum, has described this relationship very clearly in the following words: “Modern warfare particularly depends on oil, because virtually all weapons systems rely on oil-based fuel – tanks, trucks, armored vehicles, self-propelled artillery pieces, airplanes, and naval ships. For this reason, the governments and general staffs of powerful nations seek to ensure a steady supply of oil during wartime, to fuel oil-hungry military forces in far-flung operational theaters.” “Just as governments like the US and UK need oil companies to secure fuel for their global war-making capacity, so the oil companies need their governments to secure control over global oilfields and transportation routes. It is no accident, then, that the world’s largest oil companies are located in the world’s most powerful countries.” “Almost all of the world’s oil-producing countries have suffered abusive, corrupt and undemocratic governments and an absence of durable development.

Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Iraq, Iran, Angola, Colombia, Venezuela, Kuwait, Mexico, Algeria – these and many other oil producers have a sad record, which includes dictatorships installed from abroad,bloody coups engineered by foreign intelligence services, militarization of government and intolerant right-wing nationalism.” Iraq, in particular, has been the scene of a number of wars motivated by the West’s thirst for oil. During World War I, 1914-1918, the British captured the area (then known as Mesopotamia) from the Ottoman Empire after four years of bloody fighting. Although Lord Curzon (a member of the British War Cabinet who became Foreign Minister immediately after the war) denied that the British conquest of Mesopotamia was motivated by oil, there is ample evidence that British policy was indeed motivated by a desire for control of the region’s petroleum.

For example, Curzon’s Cabinet colleague Sir Maurice Hankey stated in a private letter that oil was “a first-class war aim”. Furthermore, British forces continued to fight after the signing of the Murdos Armistice. In this way, they seized Mosul, the capital of a major oil-producing region, thus frustrating the plans of the French, who had been promised the area earlier in the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement. Lord Curzon was well aware of the military importance of oil, and following the end of the First World War he remarked: “The Allied cause has floated to victory on a wave of oil”.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement essentially took away from the Arabs the autonomy that they had been promised if they fought on the side of the Allies against the Turks. Today this secret double-cross continues to be a great source of bitterness. 1 During the period between 1918 and 1930, fierce Iraqi resistance to the occupation was crushed by the British, who used poison gas, airplanes, incendiary bombs, and mobile armored cars, together with forces drawn from the Indian Army. Winston Churchill, who was Colonial Secretary at the time, regarded the conflict in Iraq as an important test of modern military-colonial methods. An article in The Guardian explains that “Churchill was particularly keen on chemical weapons, suggesting that they be used ‘against recalcitrant Arabs as an experiment…

I am strongly in favour of using poison gas against uncivilized tribes…’” In 1932, Britain granted nominal independence to Iraq, but kept large military forces in the country and maintained control of it through indirect methods. In 1941, however, it seemed likely that Germany might try to capture the Iraqi oilfields, and therefore the British again seized direct political power in Iraq by means of military force. It was not only Germany that Britain feared, but also US attempts to gain access to Iraqi oil. The British fear of US interest in Iraqi oil was soon confirmed by events. In 1963 the US secretly backed a military coup in Iraq that brought Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath Party to power.

In 1979 the western-backed Shah of Iran was overthrown, and the United States regarded the fundamentalist Shi’ite regime that replaced him as a threat to supplies of oil from Saudi Arabia. Washington saw Saddam’s Iraq as a bulwark against the militant Shi’ite extremism of Iran that was threatening oil supplies from pro-American states such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. In 1980, encouraged to do so by the fact that Iran had lost its US backing, Saddam Hussein’s government attacked Iran. This was the start of an extremely bloody and destructive war that lasted for eight years, inflicting almost a million casualties on the two nations.

Iraq used both mustard gas and the nerve gases Tabun and Sarin against Iran, in violation of the Geneva Protocol. Both the United States and Britain helped Saddam Hussein’s government to obtain chemical weapons. A chemical plant, called Falluja , was built by Britain in 1985, and this plant was used to produce mustard gas and nerve gas. Also, according to the Rigel Report to the US Senate, May 25, (1994), the Reagan Administration turned a blind eye to the export of chemical weapon precursors to Iraq, as well as anthrax and plague cultures that could be used as the basis for biological weapons. According to the Riegel Report, “records available from the supplier for the period 1985 until the present show that during this time, pathogenic (meaning disease producing) and toxigenic (meaning poisonous), and other biological research materials were exported to Iraq perusant to application and licensing by the US Department of Commerce.” In 1984, Donald Rumsfeld, Reagan’s newly appointed Middle East Envoy, visited Saddam Hussein to assure him of America’s continuing friendship, despite Iraqi use of poison gas. When (in 1988) Hussein went so far as to use poison gas against civilian citizens of his own country in the Kurdish village of Halabja, the United States worked to prevent international condemnation of the act. Indeed US support for Saddam was so unconditional that he obtained the false impression that he had a free hand to do whatever he liked in the region. On July 25, 1990, US Ambassador April Glaspie met with Saddam Hussein to discuss oil prices and how to improve US-Iraq relations. According to the transcript of the meeting, Ms Galspie assured Saddam that the US “had no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait.” She then left on vacation.

Mistaking this conversation for a green light, Saddam invaded Kuwait eight days later. By invading Kuwait, Hussein severely worried western oil companies and governments, since Saudi Arabia might be next in line. As George Bush senior said in 1990, at the time of the Gulf War, “Our jobs, our way of life, our own freedom and the freedom of friendly countries around the world would all suffer if control of the world’s great oil reserves fell into the hands of Saddam Hussein.” On August 6, 1990, the UN Security Council imposed comprehensive economic sanctions against Iraq with the aim of forcing Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait. Meanwhile, US Secretary of State James A. Baker III used arm-twisting methods in the Security Council to line up votes for UN military action against Iraq. In Baker’s own words, he undertook the process of “cajoling, extracting, threatening and occasionally buying votes”. On November 29, 1990, the Council passed Resolution 678, authorizing the use of “all necessary means” (by implication also military means) to force Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait.

There was nothing at all wrong with this, since the Security Council had been set up by the UN Charter to prevent states from invading their neighbors. However, one can ask whether the response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait would have been so wholehearted if oil had not been involved. There is much that can be criticized in the way that the Gulf War of 1990-1991 was carried out. Besides military targets, the US and its allies bombed electrical generation facilities with the aim of creating postwar leverage over Iraq. The electrical generating plants would have to be rebuilt with the help of foreign technical assistance, and this help could be traded for postwar compliance. In the meantime, hospitals and water-purification plants were without electricity. Also, during the Gulf War, a large number of projectiles made of depleted uranium were fired by allied planes and tanks.

The result was a sharp increase in cancer in Iraq. Finally, both Shi’ites and Kurds were encouraged by the Allies to rebel against Saddam Hussein’s government, but were later abandoned by the allies and slaughtered by Saddam.

The most terrible misuse of power, however, was the US and UK insistence the sanctions against Iraq should remain in place after the end of the Gulf War. These two countries used their veto power in the Security Council to prevent the removal of the sanctions. Their motive seems to have been the hope that the economic and psychological impact would provoke the Iraqi people to revolt against Saddam.

However that brutal dictator remained firmly in place, supported by universal fear of his police and by massive propaganda. The effect of the sanctions was to produce more than half a million deaths of children under five years of age, as is documented by UNICEF data. The total number of deaths that the sanctions produced among Iraqi civilians probably exceeded a million, if older children and adults are included.3 Ramsey Clark, who studied the effects of the sanctions in Iraq from 1991 onwards, wrote to the Security Council that most of the deaths “are from the effects of malnutrition including marasmas and kwashiorkor, wasting or emaciation which has reached twelve per cent of all children, stunted growth which affects twenty-eight per cent, diarrhea, dehydration from bad water or food, which is ordinarily easily controlled and cured, common communicable diseases preventable by vaccinations, and epidemics from deteriorating sanitary conditions.

There are no deaths crueler than these. They are suffering slowly, helplessly, without simple remedial medication, without simple sedation to relieve pain, without mercy.” In discussing Iraq, we mentioned oil as a motivation for western interest. Similar considerations hold also for Afghanistan. US-controlled oil companies have long had plans for an oil pipeline from Turkmenistan, passing through Afghanistan to the Arabian Sea, as well as plans for a natural gas pipeline from Turkmenistan through Afghanistan to Pakistan.

The September 11 terrorist attacks resulted in a spontaneous worldwide outpouring of sympathy for the United States, and within the US, patriotic support of President George W. Bush at a time of national crisis. Bush’s response to the attacks seems to have been to inquire from his advisors whether he was now free to invade Iraq. According to former counterterrorism chief, Richard Clarke, Bush was “obsessed” with Iraq as his principal target after 9/11. The British Prime Minister, Tony Blair, was a guest at a private White House dinner nine days after the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington. Sir Christopher Meyer, former UK Ambassador to Washington, was also present at the dinner. According to Meyer, Blair said to Bush that they must not get distracted from their main goal – dealing with the Taliban and al-Quaeda in Afghanistan, and Bush replied: “I agree with you Tony. We must deal with this first. But when we have dealt with Afghanistan, we must come back to Iraq.” Faced with the prospect of wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan, Blair did not protest, according to Meyer. During the summer of 2002, Bush and Blair discussed Iraq by telephone. A senior official from Vice-President Dick Cheney’s office who read the transcript of the call is quoted by the magazine Vanity Fair as saying: “The way it read was that come what may, Saddam was going to go; they said that they were going forward, they were going to take out the regime, and they were doing the right thing.

Blair did not need any convincing. There was no ‘Come on, Tony, we’ve got to get you on board’. I remember reading it and then thinking, ‘OK, now I know what we’re going to be doing for the next year.’” On June 1, 2002, Bush announced a new US policy which not only totally violated all precedents in American foreign policy but also undermined the United Nations Charter and international law6 . Speaking at the graduation ceremony of the US Military Academy at West Point he asserted that the United States had the right to initiate a preemptive war against any country that might in the future become a danger to the United States. “If we wait for threats to fully materialize”, he said, “we will have waited too long.”

He indicated that 60 countries might fall into this category, roughly a third of the nations of the world. The assertion that the United States, or any other country, has the right to initiate preemptive wars specifically violates Chapter 1, Articles 2.3 and 2.4, of the United Nations Charter. These require that “All members shall settle their disputes by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace, security and justice are not endangered”, and that “All members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations.” The UN Charter allows a nation that is actually under attack to defend itself, but only until the Security Council has had time to act. Bush’s principle of preemptive war was promptly condemned by the Catholic Church. Senior Vatican officials pointed to the Catholic teaching that “preventive” war is unjustifiable, and Archbishop Renato Martino, prefect of the Vatican Council for Justice and Peace, stated firmly that “unilateralism is not acceptable”. However, in the United States, the shocking content of Bush’s West Point address was not fully debated. The speech was delivered only a few months after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and the US supported whatever exceptional measures its President thought might be necessary for the sake of national security.

American citizens, worried by the phenomenon of terrorism, did not fully appreciate that the principle of preemptive war could justify almost any aggression, and that in the long run, if practiced by all countries, it would undermine the security of the United States as well as that of the entire world. During the spring of 2003, our television and newspapers presented us with the spectacle of an attack by two technologically superior powers on a much less industrialized nation, a nation with an ancient and beautiful culture. The ensuing war was one-sided. Missiles guided by laser beams and signals from space satellites were more than a match for less sophisticated weapons. Speeches were made to justify the attack. It was said to be needed because of weapons of mass destruction (some countries are allowed to have them, others not). It was said to be necessary to get rid of a cruel dictator (whom the attacking powers had previously supported and armed).

But the suspicion remained that the attack was resource-motivated. It was about oil, or at least largely about oil. The war on Iraq was also designed to destroy a feared enemy of Israel. The Nobel Peace Prize winner, Maidread Corrigan Maguire estimates that US and UK actions between 1990 and 2012 killed 3.3 million people, including 750,000 children. Against the historical background discussed above, we can appreciate the enormous hypocrisy of Obama’s claim that the bombing of Iraq during his administration was “humanitarian”.

7 Some contributions of Islamic culture

Figure 3: An example of Iranian art

At a time when the corporate-controlled media of Europe and the United States are doing their utmost to fill us with poisonous Islamophobia, it is perhaps a useful antidote to remember the great role that Islamic civilization played in preserving, enlarging and transmitting to us the knowledge and culture of the ancient world. After the burning of the great library at Alexandria and the destruction of Hellenistic civilization, most of the books of the classical Greek and Hellenistic philosophers were lost.

However, a few of these books survived and were translated from Greek, first into Syriac, then into Arabic and finally from Arabic into Latin. By this roundabout route, fragments from the wreck of the classical Greek and Hellenistic civilizations drifted back into the consciousness of the West. The Roman empire was ended in the 5th century A.D. by attacks of barbaric Germanic tribes from northern Europe. However, by that time, the Roman empire had split into two halves. The eastern half, with its capital at Byzantium (Constantinople), survived until 1453, when the last emperor was killed vainly defending the walls of his city against the Turks.

The Byzantine empire included many Syriac-speaking subjects; and in fact, beginning in the 3rd century A.D., Syriac replaced Greek as the major language of western Asia. In the 5th century A.D., there was a split in the Christian church of Byzantium; and the Nestorian church, separated from the official Byzantine church. The Nestorians were bitterly persecuted by the Byzantines, and therefore they migrated, first to Mesopotamia, and later to south-west Persia. (Some Nestorians migrated as far as China.) During the early part of the middle ages, the Nestorian capital at Gondisapur was a great center of intellectual activity. The works of Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates, Euclid, Archimedes, Ptolemy, Hero and Galen were translated into Syriac by Nestorian scholars, who had brought these books with them from Byzantium. Among the most distinguished of the Nestorian translators were the members of a family called Bukht-Yishu (meaning “Jesus hath delivered”), which produced seven generations of outstanding scholars. Members of this family were fluent not only in Greek and Syriac, but also in Arabic and Persian. In the 7th century A.D., the Islamic religion suddenly emerged as a conquering and proselytizing force. Inspired by the teachings of Mohammad (570 A.D. – 632 A.D.), the Arabs and their converts rapidly conquered western Asia, northern Africa, and Spain. During the initial stages of the conquest, the Islamic religion inspired a fanaticism in its followers which was often hostile to learning.

However, this initial fanaticism quickly changed to an appreciation of the ancient cultures of the conquered territories; and during the middle ages, the Islamic world reached a very high level of culture and civilization. Thus, while the century from 750 to 850 was primarily a period of translation from Greek to Syriac, the century from 850 to 950 was a period of translation from Syriac to Arabic. It was during this latter century that Yuhanna Ibn Masawiah (a member of the Bukht-Yishu family, and medical advisor to Caliph Harun al-Rashid) produced many important translations into Arabic. The skill of the physicians of the Bukht-Yishu family convinced the Caliphs of the value of Greek learning; and in this way the family played an extremely important role in the preservation of the western cultural heritage.

Caliph al-Mamun, the son of Harun al-Rashid, established at Baghdad a library and a school for translation, and soon Baghdad replaced Gondisapur as a center of learning. The English word “chemistry” is derived from the Arabic words “al-chimia”, which mean “the changing”. The earliest alchemical writer in Arabic was Jabir (760-815), a friend of Harun al-Rashid. Much of his writing deals with the occult, but mixed with this is a certain amount of real chemical knowledge. For example, in his Book of Properties, Jabir gives a recipe for making what we now call lead hydroxycarbonate (white lead), which is used in painting and pottery glazes: Another important alchemical writer was Rahzes (c. 860 – c. 950). He was born in the ancient city of Ray, near Teheran, and his name means “the man from Ray”. Rhazes studied medicine in Baghdad, and he became chief physician at the hospital there.

He wrote the first accurate descriptions of smallpox and measles, and his medical writings include methods for setting broken bones with casts made from plaster of Paris. Rahzes was the first person to classify substances into vegetable, animal and mineral. The word “al-kali”, which appears in his writings, means “the calcined” in Arabic.

It is the source of our word “alkali”, as well as of the symbol K for potassium. The greatest physician of the middle ages, Avicinna, (Abu-Ali al Hussain Ibn Abdullah Ibn Sina, 980-1037), was also a Persian, like Rahzes. More than a hundred books are attributed to him. They were translated into Latin in the 12th century, and they were among the most important medical books used in Europe until the time of Harvey. Avicinina also wrote on alchemy, and he is important for having denied the possibility of transmutation of elements. In mathematics, one of the most outstanding Arabic writers was al-Khwarizmi (c. 780 – c. 850). The title of his book, Ilm al-jabr wa’d muqabalah, is the source of the English word “algebra”. In Arabic al-jabr means “the equating”. Al-Khwarizmi’s name has also become an English word, “algorism”, the old word for arithmetic. Al-Khwarizmi drew from both Greek and Hindu sources, and through his writings the decimal system and the use of zero were transmitted to the West. One of the outstanding Arabic physicists was al-Hazen (965-1038).

He did excellent work in optics, and in this field he went far beyond anything done by the Greeks. Al-Hazen studied the reflection of light by the atmosphere, an effect which makes the stars appear displaced from their true positions when they are near the horizon; and he calculated the height of the atmospheric layer above the earth to be about ten miles. He also studied the rainbow, the halo, and the reflection of light from spherical and parabolic mirrors. In his book, On the Burning Sphere, he shows a deep understanding of the properties of convex lenses. Al-Hazen also used a dark room with a pin-hole opening to study the image of the sun during an eclipse. This is the first mention of the camera obscura, and it is perhaps correct to attribute the invention of the camera obscura to al-Hazen. Another Islamic philosopher who had great influence on western thought was Averroes, who lived in Spain from 1126 to 1198. His writings took the form of thoughtful commentaries on the works of Aristotle. He shocked both his Muslim and his Christian readers by maintaining that the world was not created at a definite instant, but that it instead evolved over a long period of time, and is still evolving. In the 12th century, parts of Spain, including the city of Toledo, were reconquered by the Christians. Toledo had been an Islamic cultural center, and many Muslim scholars, together with their manuscripts, remained in the city when it passed into the hands of the Christians. Thus Toledo became a center for the exchange of ideas between east and west; and it was in this city that many of the books of the classical Greek and Hellenistic philosophers were translated from Arabic into Latin. It is interesting and inspiring to visit Toledo.

A tourist there can see ample evidence of a period of tolerance and enlightenment, when members of the three Abrahamic religions, Christianity, Judaism and Islam , lived side by side in harmony and mutual respect, exchanging important ideas which were to destined to become the foundations of our modern civilization. One can also see a cathedral, a mosque and a synagogue, in each of which craftsmen from all three faiths worked cooperatively to produce a beautiful monument to human solidarity.

8 Syria and Lebanon

World War II comes to Syria

Figure 4: Bayard Dodge, President of the American University of Beirut, and his fmily. Their residence was called Marquand House.

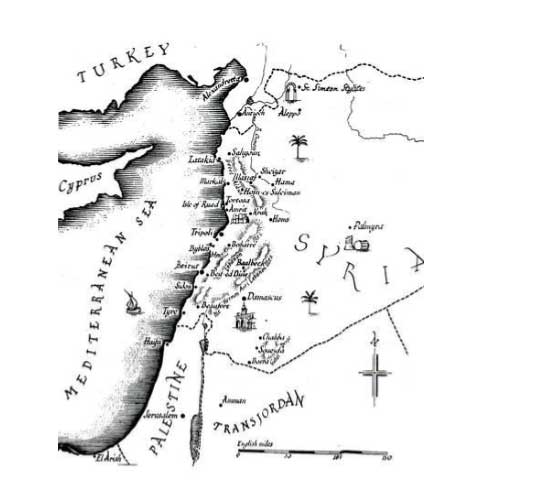

Figure 5: A map of Syria as it was when my family lived there. Tyre, Sidon and Biblos are ancient Phoenician cities.

Wartime regulations and blackouts began in 1939. After the fall of Paris in 1940, the Vichy government was in control of Lebanon, and Beirut was full of Italian and German troops. Describing this period, Bayard Dodge, President of the American University of Beirut, wrote: “The Vichy r´egeme in Beirut lasted from the early summer of 1940 until July 15, 1941. Prices rose, as petroleum products, sugar, rice and all sorts of imported goods became rare. Large supplies of grain disappeared and newspapers were filled with proGerman propaganda, which gained steadily in intensity. By May, 1941, the Germans had control of the entire region between the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf. Everybody took it for granted that the German conquest of Greece and Crete would be followed by a similar invasion of Lebanon and Syria…” President Dodge stayed in Beirut but most of the American and European members of the AUB faculty left for British-controlled Palestine with only a few hours notice. The students from outside the French mandated territory were sent home, but the university remained open for the remaining students.

For thirteen months there was a virtual blitz, with bombardments night after night. In her book, Legacy to Lebanon, Grace Dodge Guthrie has described her parent’s experiences with the following words: “On June 12, 1940, a very ill soldier whom [my mother] had seen in the morning, died in the early afternoon. At 3:15 the next morning my parents heard planes flying low, severe antiaircraft attacks and machine-gun firing.

Three large pieces of flying shrapnel, streaking red in the night, dropped in the garden, the porch roof, and extensively in the AUB grounds. When she visited the prisoners and the wounded in the military hospital, ambulances were arriving with badly wounded Lebanese, Colonials, and two British dead bodies. “A year later, at 4:15 a.m. on June 16, 1941, [my parents] were roused by loud but distant gunfire off the point out at sea. Soon the sky glowed with bright flares, and the air was rent by rapid firing. Two French destroyers were repulsing an attack by five British boats off the point, and guns were firing on shore. Later that morning, most trucks, busses and cars were commandeered. “It was becoming increasingly difficult for people to find transport to evacuate… On 23rd June, Mother reported ‘the biggest battle yet: flares, machine- guns, antiaircraft guns, reconnaissance planes and big guns on shore. British are attacking villages, Abeih ([our] first summer home) etc. Much negotiation is going on between General Dentz and the British… One of our soldier patients told the doctor that many of his regiment went over to de Gaulle in South Lebanon.’ “On July 1st, a common occurrence during the war years, water and electricity were cut off all day.

After bad raids all night, the Beirut radio went out. A shell burst on the AUB campus. Bombs and guns continued to shake the houses with earsplitting noise for six straight nights. Stores were burned and houses demolished. Masses of people were escaping to the mountains and the campus filling up at night with people seeking safety. “On the morning of July 10th the French scuttled an old British ship near the St. Georges Hotel. A second ship was blown up at noon and a third British oil boat burned in the afternoon. My parents visited the port and watched the enormous clouds of black smoke and flames.

The French High Command were burning papers and packing to go north.” The end of the fighting in Beirut came on July 14, 1941. President Dodge wrote: “In the middle of the night the university watchman picked up a piece of green paper, dropped from a British plane. He woke up the Director of Grounds and Buildings, who brought it to Marquand House. The paper was an ultimatum, which stated that unless General Dentz should stop his resistance before daybreak, the Free French and British would bombard Beirut. “When Consul General Engert saw the ultimatum, he called on General Dentz, who, clad in his pajamas, talked with him for two hours and finally agreed to make an armistice. “The armistice was signed at Acre on July 14, 1941… On July 15th the Australian troops entered Beirut, and the next day the French and British Generals, Catroux and Wilson, made an official entry. When General de Gaulle reached the city, he and General Catroux very courteously called at Marquand House.” Mrs. Dodge wrote to her daughter Grace; “We’ll never forget the day de Gaulle came for a tea party in our garden!” Through General de Gaulle’s influence, Lebanon obtained its independence, not only from France but also from Syria. In 1943 the first Lebanese elections were held. At the time the majority of Lebanese citizens were Christians, but Muslims formed a large minority. Government posts were carefully balanced to give representation to both groups.

Israel’s invasions of Lebanon

As mentioned above, the present-day Lebanese towns Tyre, Sidon and Biblos date back to the Phoenecians, who traded throughout the Mediterranean, and even to places in the Atlantic, such as Scotland. Ceder wood from Lebanon was once prized throughout the ancient world. Like their Phoenecian ancestors, the Lebanese people of today are primarily interested in trade, economic prosperity, and the enjoyment of life. In the 1960’s Lebanon did indeed enjoy great prosperity as the banking center of the Middle East.

It was also a place where tourists from both Europe and the Middle East spent their vacations. One could buy gold bars in Beirut’s bazzars, and luxury hotels had sprung up everywhere along the formerly empty coastline near Beirut. Tragically, however, Lebanon became the scene of proxy wars both in the Cold War and in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Beirut’s St. George Hotel became a meeting place for spys from both sides in the Cold War, and Palistinian refugees in southern Lebanon became a source of conflict with Israel. I revisited Beirut, the place of my birth. in 1965. (Between 1926 and 1940, my father had taught medicine at the American University of Beirut, and I was born there in 1933.) As mentioned, the 1960’s were a period of great prosperity for Lebanon, but there were signs of trouble. Travel to the southern part of Lebanon was forbidden because of the political sensitivity of the Palistinian refugee camps which were situated there.

During my 1965 stay in Beirut, I visited two childhood friends, a husband and wife, at their home in the mountains above Beirut. Their fathers, like mine, had had been professors at the American University of Beirut. Now both husband and wife were also professors at the AUB, following in their parents’ footsteps. The wife, Erica Cruickshank Dodd was Professor of Byzantine Art History, while her husband, Peter Dodd, was the Professor of Socioligy. Peter was an expert on conflict resolution, and the author of a book entitled River Without Bridges. This title had a double meaning. It referred to the Jordan River, where all the bridges had been destroyed by bombs, and also to the seemingly unbridgable nature of the conflicts in the region. He said to me “I won’t even attempt to describe to you the present political situation in Lebanon. It is unbelievably complicated.” Both Peter and Erica thought that Beirut was a dangerous place, and that there was especially a danger that Peter would be kidnapped by one or another of the groups that were competing for power. But they stayed because of Peter’s professional interest in the situation. In 1973, an Israeli commando raid on Lebanon took place. Speedboats were launched from offshore Israeli missile boats, and several high-ranking members of the Palestine Liberation Organization were murdered in their homes by the Israeli commandos. Full-scale Israeli military invasions of Lebanon took place in 1978. 1982, 1993, 1996, amd 2006.

The Lenanese Civil War, 1975-1990

The Lebanese Civil War was in part a proxy war between America and Russia amd partly a result of the Arab-Israeli conflict over Palestine. Both sides in the Cold War sent weapons to Lebanon, and these weapons resulted in the establishment of highly-armed private mlitia groups. A situation of political anarchy resulted, because conflicting militia groups were more highly armed than the government. Religion was also mixed into the civil war. Beirut was divided into neighborhoods in which Christians or Mislims had majorities. There was a story of a dinner party during which the host excused himself, saying that he would be back in a few minutes. He then went up to the flat roof of his house and fired a few morter shells into another part of the city. The Lebanese Civil War resulted in approximately 120,000 deaths, 76,000 internally displaced people, and the exodus of almost a million people from Lebanon.

Syrian refugees in Lebanon

Today, in proportion to its size, Lebanon hosts more refugees from the war in Syria than any other country. As of October 2016, Lebanon hosted 1.5 million Syrian refugees (according to Government of Lebanon estimates, including 1 million registered with UNHCR), half of them children (below 18 years old).

9 Saudi Arabia and Yemen

US and UK weapons flow into Saudi Arabia, and in return, oil flow out. Both the weapons and the oil are highly damaging. Continued extraction and use of oil must stop within a decade if tipping points are to be avoided, beyond which feedback loops will take over and catastrophic climate change will be unavoidable, no matter what we do. The weapons have caused enormous amounts of human suffering, both in Yemen, where Saudi Arabia is carrying out a brutal war, and in Syria, where the arms are being supplied to fanatical Islamist groups such as ISIS. In Yemen, many thousands of civilians have been killed, and there is a threat of a very large-scale famine, involving at least a million people. Nevertheless, dispite atrocities, the West’s love affair with Saudi Arabia continues because of the profits earned on the weapons and the oil. This stiuation was briefly interrupted when a journalist, Jamal Kashoggi, was (according to reports) “accidentally” hacked to pieces with a bone saw by a team of Saudi agents while applying for a marriage liscence at the Saudi Arabian Embassy in Turkey. It seems that Kashoggi was about to reveal Saudi Arabia’s use of chemical weapons in Yemen. This grusome murder made headlines, but relations between Saudi Arabia and the West soon returned to normal. After all, it is money that rules the world.

10 Politeness in multi-ethnic societies

The attack on Charlie Hebdo, in which 12 people were killed, claimed massive media attention worldwide. Everyone agreed that freedom of speech and democracy had been brutally attacked, and many people proclaimed “Je suis Charlie!”, in solidarity with the murdered members of the magazine’s staff. In Denmark, it was proposed that the offending cartoons of the prophet Mohammad should be reprinted in major newspapers. However, in the United States, there was no such proposal, and in fact, US television viewers were not even allowed to see the drawings that had provoked the attack.

How is this difference between Denmark and the US to be explained? Denmark is a country with a predominantly homogeneous population, which only recently has become more diverse through the influx of refugees from troubled parts of the world. Thus, I believe, Denmark has not yet had time to learn that politeness is essential for preventing conflicts in a multi-ethnic society. On the other hand, the United States has lived with the problem for much longer. During most of its history, the US has had substantial Spanish-speaking and Italianspeaking minorities, as well as great religious diversity.

During the 1960’s the civil rights movement fought against racial prejudice and gradually achieved most of its goals. Thus, over a very long period of time, the United States learned to avoid racial and religious insults in its media, and this hard-earned wisdom has allowed the very markedly multiethnic US society to function with a minimum of racial and religious conflicts. Is this a lesson that the world as a whole needs to learn? I strongly believe that it is.

Globally, we are in great need of a new ethic, which regards all humans as brothers and sisters, regardless of race, religion or nationality. Human solidarity will become increasingly important in the future, as stress from climate change and the vanishing of nonrenewable resources becomes more pronounced. To get through the difficult time ahead of us, we will need to face the dangers and challenges of the future arm in arm, respecting each other’s differing beliefs, and emphasizing our common humanity rather than our differences.

11 Oil and conflicts in the Middle East

Petroleum accounts for 90% of the energy used in transportation, and it is also particularly important in agriculture. Thus it is worrying that we will encounter high and constantly increasing oil prices at just the moment when an unprecedentedly large global population will be putting pressure on the food supply. High oil prices will be reflected in high food costs. Even today we can see nations where famine occurs because their weak economies make the poorest countries unable to buy and import food.

These vulnerable nations will be hit still harder by famine in the future. The United States uses petroleum at the rate of more than 7 billion barrels (7 Gb) per year, while that country’s estimated reserves and undiscovered resources are respectively 50.7 Gb and 49.0 Gb. Thus if the United States were to rely only on its own resources for petroleum, then, at the 2001 rate of use, these would be exhausted within 14 years. In fact, the United States already imports more than half of its oil. According to the “National Energy Policy” report (sometimes called the “Cheney Report” after its chief author) US domestic oil production will decline from 3.1 Gb/y in 2002 to 2.6 Gb/y in 2020, while US consumption will rise from 7.2 Gb/y to 9.3 Gb/y. Thus the United States today imports 57% of its oil, but the report predicts that by 2020 this will rise to 72%. The predicted increment in US imports of oil between 2002 and 2020 is greater than the present combined oil consumption of China and India.

It is clear from these figures that if the United States wishes to maintain its enormous rate of petroleum use, it will have to rely on imported oil, much of it coming from regions of the world that are politically unstable, or else unfriendly to America, or both. This fact does much to explain the massive US military presence in oil-rich regions of the world. Speaking at a National Energy Summit, on March 19, 2001, Secretary of Energy Spencer Abraham stated that “America faces a major energy supply crisis over the next two decades. The failure to meet this challenge will threaten our nation’s economic prosperity, compromise our security, and literally alter the way we lead our lives.” There is a close relationship between petroleum and war. James A. Paul, Executive Director of the Global Policy Forum, has described this relationship very clearly in the following words: “Modern warfare particularly depends on oil, because virtually all weapons systems rely on oil-based fuel – tanks, trucks, armored vehicles, self-propelled artillery pieces, airplanes, and naval ships.

For this reason, the governments and general staffs of powerful nations seek to ensure a steady supply of oil during wartime, to fuel oil-hungry military forces in far-flung operational theaters.” “Just as governments like the US and UK need oil companies to secure fuel for their global war-making capacity, so the oil companies need their governments to secure control over global oilfields and transportation routes. It is no accident, then, that the world’s largest oil companies are located in the world’s most powerful countries.” “Almost all of the world’s oil-producing countries have suffered abusive, corrupt and undemocratic governments and an absence of durable development. Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Iraq, Iran, Angola, Colombia, Venezuela, Kuwait, Mexico, Algeria – these and many other oil producers have a sad record, which includes dictatorships installed from abroad, bloody coups engineered by foreign intelligence services, militariization of government and intolerant right-wing nationalism.” Iraq, in particular, has been the scene of a number of wars motivated by the West’s thirst for oil. During World War I, 1914-1918, the British captured the area (then known as Mesopotamia) from the Ottoman Empire after four years of bloody fighting.

Although Lord Curzon denied that the British conquest of Mesopotamia was motivated by oil, there is ample evidence that British policy was indeed motivated by a desire for control of the region’s petroleum. For example, Curzon’s Cabnet colleague Sir Maurice Hankey stated in a private letter that oil was “a first-class war aim”. Furthermore, British forces continued to fight after the signing of the Murdos Armistice. In this way, they seized Mosul, the capital of a major oil-producing region, thus frustrating the plans of the French, who had been promised the area earlier in the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement. Lord Curzon was well aware of the military importance of oil, and following the end of the First World War he remarked: “The Allied cause has floated to victory on a wave of oil”.

During the period between 1918 and 1930, fierce Iraqi resistance to the occupation was crushed by the British, who used poison gas, airplanes, incendiary bombs, and mobile armored cars, together with forces drawn from the Indian Army. Winston Churchill, who was Colonial Secretary at the time, regarded the conflict in Iraq as an important test of modern military-colonial methods. In 1932, Britain granted nominal independence to Iraq, but kept large military forces in the country and maintained control of it through indirect methods. In 1941, however, it seemed likely that Germany might try to capture the Iraqi oilfields, and therefore the British again seized direct political power in Iraq by means of military force. It was not only Germany that Britain feared, but also US attempts to gain access to Iraqi oil. The British fear of US interest in Iraqi oil was soon confirmed by events. In 1963 the US secretly backed a military coup in Iraq that brought Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath Party to power.5 In 1979 the western-backed Shah of Iran was overthrown, and the United States regarded the fundamentalist Shi’ite regime that replaced him as a threat to supplies of oil from Saudi Arabia. Washington saw Saddam’s Iraq as a bulwark against the militant member of the British War Cabinet who became Foreign Minister immediately after the war This was not the CIA’s first sponsorship of Saddam: In 1959 he had been part of a CIA-authorized six-man squad that tried to assassinate the Iraqi Prime Minister, Abd al-Karim Qasim.

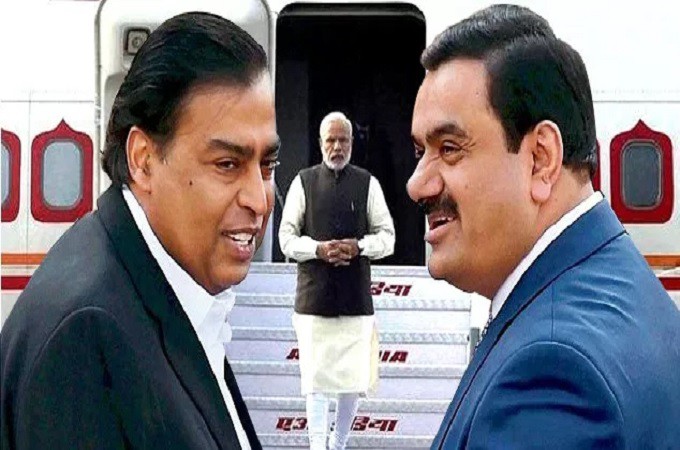

Figure 6: Donald Rumsfeld and his close friend, Saddam Hussein

Shi’ite extremism of Iran that was threatening oil supplies from pro-American states such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. In 1980, encouraged to do so by the fact that Iran had lost its US backing, Saddam Hussein’s government attacked Iran. This was the start of a extremely bloody and destructive war that lasted for eight years, inflicting almost a million casualties on the two nations. Iraq used both mustard gas and the nerve gases Tabun and Sarin against Iran, in violation of the Geneva Protocol.

Both the United States and Britain helped Saddam Hussein’s government to obtain chemical weapons. A chemical plant, called Falluja 2, was built by Britain in 1985, and this plant was used to produce mustard gas and nerve gas. Also, according to the Riegel Report to the US Senate, May 25, (1994), the Reagan Administration turned a blind eye to the export of chemical weapon precursors to Iraq, as well as anthrax and plague cultures that could be used as the basis for biological weapons. According to the Riegel Report, “records available from the supplier for the period 1985 until the present show that during this time, pathogenic (meaning disease producing) and toxigenic (meaning poisonous), and other biological research materials were exported to Iraq perusant to application and licensing by the US Department of Commerce.” In 1984, Donald Rumsfeld, Reagan’s newly appointed Middle East Envoy, visited Saddam Hussein to assure him of America’s continuing friendship, despite Iraqi use of poison gas. When (in 1988) Hussein went so far as to use poison gas against civilian citizens of his own country in the Kurdish village of Halabja, the United States worked to prevent international condemnation of the act. Indeed US support for Saddam was so unconditional that he obtained the false impression that he had a free hand to do whatever he liked in the region. On July 25, 1990, US Ambassador April Glaspie met with Saddam Hussein to discuss oil prices and how to improve US-Iraq relations. According to the transcript of the meeting, Ms Galspie assured Saddam that the US “had no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait.” She then left on vacation.

Mistaking this conversation for a green light, Saddam invaded Kuwait eight days later. By invading Kuwait, Hussein severely worried western oil companies and governments, since Saudi Arabia might be next in line. As George Bush senior said in 1990, at the time of the Gulf War, “Our jobs, our way of life, our own freedom and the freedom of friendly countries around the world would all suffer if control of the world’s great oil reserves fell into the hands of Saddam Hussein.” On August 6, 1990, the UN Security Council imposed comprehensive economic sanctions against Iraq with the aim of forcing Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait. Meanwhile, US Secretary of State James A. Baker III used arm-twisting methods in the Security Council to line up votes for UN military action against Iraq.

In Baker’s own words, he undertook the process of “cajoling, extracting, threatening and occasionally buying votes”. On November 29, 1990, the Council passed Resolution 678, authorizing the use of “all necessary means” (by implication also military means) to force Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait. There was nothing at all wrong with this, since the Security Council had been set up by the UN Charter to prevent states from invading their neighbors. However, one can ask whether the response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait would have been so wholehearted if oil had not been involved. There is much that can be criticized in the way that the Gulf War of 1990-1991 was carried out.

Besides military targets, the US and its allies bombed electrical generation facilities with the aim of creating postwar leverage over Iraq. The electrical generating plants would have to be rebuilt with the help of foreign technical assistance, and this help could be traded for postwar compliance. In the meantime, hospitals and water-purification plants were without electricity. Also, during the Gulf War, a large number of projectiles made of depleted uranium were fired by allied planes and tanks. The result was a sharp increase in cancer in Iraq. Finally, both Shi’ites and Kurds were encouraged by the Allies to rebel against Saddam Hussein’s government, but were later abandoned by the allies and slaughtered by Saddam. The most terrible misuse of power, however, was the US and UK insistence the sanctions against Iraq should remain in place after the end of the Gulf War.

These two countries used their veto power in the Security Council to prevent the removal of the sanctions. Their motive seems to have been the hope that the economic and psychological impact would provoke the Iraqi people to revolt against Saddam. However that brutal dictator remained firmly in place, supported by universal fear of his police and by massive propaganda. The effect of the sanctions was to produce more than half a million deaths of children under five years of age, as is documented by the UNICEF data shown in Figure 1. The total number of deaths that the sanctions produced among Iraqi civilians probably exceeded a million, if older children and adults are included.

Ramsey Clark, who studied the effects of the sanctions in Iraq from 1991 onwards, wrote to the Security Council that most of the deaths “are from the effects of malnutrition including marasmas and kwashiorkor, wasting or emaciation which has reached twelve per cent of all children, stunted growth which affects twenty-eight per cent, diarrhea, dehydration from bad water or food, which is ordinarily easily controlled and cured, common communicable diseases preventable by vaccinations, and epidemics from deteriorating sanitary conditions. There are no deaths crueler than these. They are suffering slowly, helplessly, without simple remedial medication, without simple sedation to relieve pain, without mercy.”

12 OPEC oil and climate change

In an amazing display of collective schizophrenia, our media treat oil production and the global climate emergency as though they were totally disconnected. But the use of all fossil fuels, including oil, must stop almost immediately if the world is to have a chance of avoiding uncontrollable and catastrophic climate change.

The recent Doha summit meeting of the Oil Producing and Exporting Countries (OPEC) aimed at reaching an agreement on limiting the production of oil. This aim did not stem from the climate emergency but rather a from desire to raise oil prices and profits. However, the OPEC meeting failed to reach an agreement. Production continues to be extremely high and prices low.6 Our high-energy lifestyles continue. Our profligate use of fossil fuels continues as though the life-threatening climate emergency did not exist. Meanwhile, temperatures in 2018 have totally smashed all previous records, and this is especially pronounced in the Arctic and Antarctic regions. Polar ice caps are melting in an alarmingly rapid and non-linear way. The rate of melting of the icecaps is far greater than predicted by conventional modeling which does not include feedback loops. Many island nations and coastal cities are threatened, not in the very distant future, but by the middle of our present century.

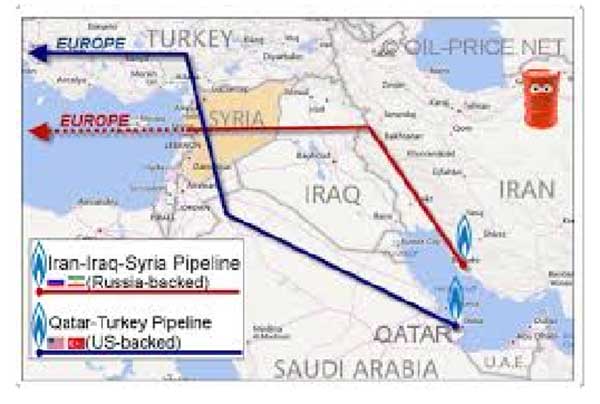

Figure 7: Pipeline wars. The thirst for oil has been a strong motivating force for wars in the Middle East. A second motive has been Israel’s wish to have military hegemony in the region.

13 September 11, 2001

On the morning of September 11, 2001, two hijacked airliners were deliberately crashed into New York’s World Trade Center, causing the collapse of of three skyscrapers and the deaths of more than three thousand people. Almost simultaneously, another hijacked airliner was driven into the Pentagon in Washington DC, and a fourth hijacked plane crashed in a field in Pennsylvania. The fourth plane probably was to have made a suicide attack on the White House or the Capitol, but passengers on the airliner became aware what was happening through their mobile telephones, and they overpowered the hijackers.