His visit struck a sour note. The Australian prime minister Scott Morrison was making an effort to show he cared: about those intangible things called borders, secure firm and shut to the unwanted human matter coming by sea. The distant Australian territory of Christmas Island was selected to assist in coping with arrivals from Manus and Nauru Island needing medical treatment. Having lost the vote in parliament on preventing the move, the Morrison government has does its best to ensure that a cruel element remains.

During the visit, Morrison rationalised the re-opening as the fault of the opposition. “As Prime Minister, I closed the Christmas Island detention centre and got all the children off Nauru.” The Labor Party had “voted to weaken our borders and we have acted on official advice to reopen Christmas Island.” The facilities provided “a deterrent to people smugglers and to anyone who thinks they can game the system to get to Australia.” The mythology persists.

There are parallels with atrocity and jail tourism (fancy seeing concentration camps?) in a man being filmed going through such facilities, though this time, they are intended for full use rather than being a site for instructive purposes or moral outrage. Should Australians ever wake up to the full implications of what their government does in their name, such camps might become appropriate measures of a gulag mentality that paralysed any sensible discourse on refugees for a generation.

Being a man obsessed by the moving image (once and adman always an adman), Morrison ensured that cameras never left their focus; the prime minister was keen to push the credentials of the North West Point Detention Centre. He made a pit stop at a library. (Cue necessary movement of arms to bookshelves; expansive hand movements). He even found himself gazing at a lavatory. “It was short,” recalled a disgusted resident, John Richardson. Small businessman Troy Watson was also a touch bitter. “It’s got be some sort of publicity stunt.”

And stunt it is. It belies the fact that Australia is facing, under its current Home Affairs minister Peter Dutton, a record number of asylum seekers who are entering as tourists and economise on their status. They simply prefer to do so by that more approved mode of transport: the plane. As former Department of Immigration official Abul Rizvi points out with sharp relevance, “People arriving on visitor visas and changing their status onshore constituted an astonishing 24 percent of net migration in 2017-8, the mark of a visa system out of control.” Dutton, he charges, has no genuine immigration or refugee policy to speak of.

The re-conversion of Christmas Island into a detention centre has also provided some encouragement to locals. With refugee arrivals comes a market, an opportunity to expending cash. Human cargo can have its value: increased number of personnel, more individuals to clothe and feed on the island, more, for want of a better term, services, however poor. As Watson had to concede, “The economy on Christmas Island has been low for a good 12 months now, all local businesses including our own have certainly suffered.”

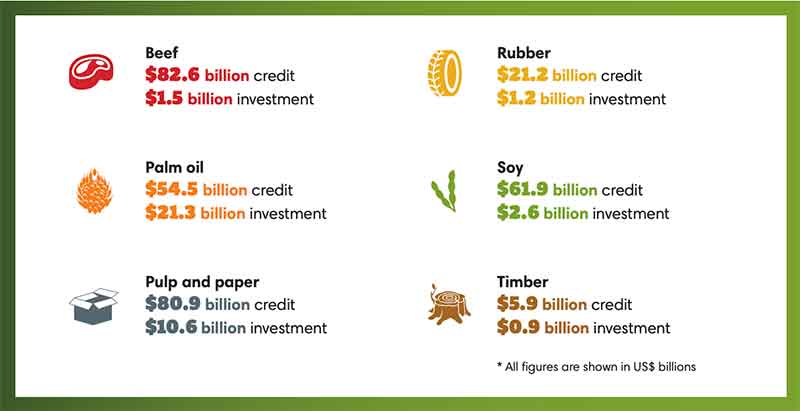

The company providing such services Serco, is a UK-based security outfit that deserves being reviled. Self-touted as adept in taking over outsourced services, the company specialises in running defence, health, transport, justice and immigration, and “citizen services”. Forty percent of its work comes from the UK, with about half that share drawn from Australia, where it is involved in some 11 Australian immigration detention centres.

Lodged in the trove of corporate devilry known as the Paradise Papers is an assessment by a Mauritius-based law firm Appleby which regards the company as replete with “problems, failures, fatal errors and overcharging”. This, it’s fair to say, comes with the troubled territory and again reminds us that privatising the swathe of public sector services does much to drain rather than save the treasury. It also serves to corrupt the delivery of such services. Again, deterrence comes before quality; harshness before vision.

The legal firm in question furnishes eager corporate watchers with a spicy note: in 2013, Serco was exposed, along with another charming counterpart, G4S, for overcharging the public purse by millions in the field of electronic tagging. This delightful resume leads to the inevitable conclusion: the company is a “high risk” client that leaves more problems than solutions.

Despite such a patchy record, the company’s 2017 annual report is bright and confident, though concedes the following: “governments have become much more skilled at contracting and focused on risk-transfer; as a consequence margins and risk-adjusted returns earned by many suppliers to governments are much lower today than they were ten years ago”. Not to be discouraged, the report picks up with the confident assertion that “the world still needs prisons, will need to manage immigration, and provide healthcare and transport, and that these services will be highly people-intensive for decades to come.” Crudely and abysmally, the company might just be right, awaiting the commencement of the Christmas Island contract with mawkish eagerness.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]