Currently, the impression that things can be made to happen even without the participation of the working class is being sought to be furthered by employers and managements. What to speak of marginalization, it is the evaporization of the worker from public consciousness that is being attempted. Just visualize the surrealistic pilgrim’s progress that we have covered in the past three decades or so. In better days, the practice was that from time to time, as conditions on the ground dictated, workers would, through their recognized Union or Unions, place their demands before the management after which the process of negotiation, of give and take, would begin. But, as things stand today, the idea of negotiation looks like ancient history. Conditions have so worsened that a charter of demands is arbitrarily drawn by a management and given to the Union to abide by. Unions, where they still exist, have been rendered redundant for the most part and workers are often practically at the mercy of employers. If this is the situation in the so-called organized sector, one can well imagine the fate of millions of working men and women in the unorganized sector. While there is a virtual loot of human and other resources by private companies, aided by solicitous governments at the Centre and in the States, elected representatives of the people look on with detachment when they are not actively engaged in the outrage.

Ironically, many workers’ Unions, even large ones, have disappeared or are disappearing while employers’ unions like CII, FICCI and the different Chambers of Commerce are gaining in strength each day. Workers, driven to the corner, appear to have lost the strength to even flail their arms in self-defence. What even the alley cat routinely does, they cannot.

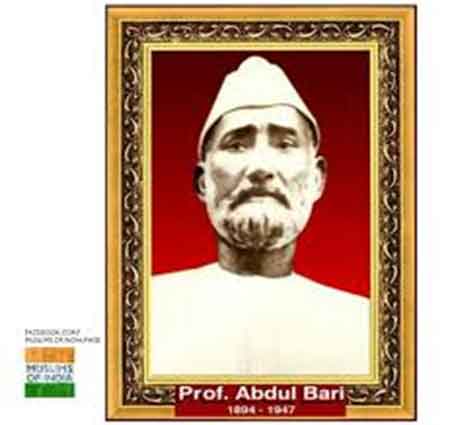

In this essay, I have tried, among other things, to resurrect the character, teachings and deeds of a great labour leader named Professor Abdul Bari (1892-1947), who has for many decades now been the target of a malicious campaign mounted by successive managements of Tata Iron and Steel Company (Tisco) in Jamshedpur. The belief appears to exist in certain quarters that the morale of the working class can be dented if a consistent campaign is carried out against its most revered leaders.

Professor Bari’s work as a labour leader at a time of political tension and industrial strife, meaning the 1930s and 1940s, took him to steel plants in Burnpur and Kulti in West Bengal as well as to nearby coalfields in Jharia and Raniganj. Though he originally belonged to Patna where he was a teacher, which explains for the honorific before his name, it was to the toiling masses of Jamshedpur (read the workers of Tisco and The Tinplate Company of India) that he gave his best years. Successive managements of Tisco have tried their desperate best to erase him from the memory of the people of Jamshedpur. Sadly, one cannot say corporate exertions towards that end have entirely failed.

“Curiously, in the Professor’s house in a narrow Patna lane, there was only one rupee (after his death). The man who had negotiated for crores of rupees for the working class, was in fact poorer than even the poorest factory or mine worker. No wonder, he is still remembered as the greatest champion of the working class even by those who never saw him. No labour rally, including those of his opponents (when he was alive) began without the loud shouting of the slogan, Professor Abdul Bari zindabad !” – R. L. Verma, seasoned trade-union activist, in a souvenir published by Bihar Association, Jamshedpur.

A diametrically different impression about the man is put forth by another chronicler. “In 1937, Professor Abdul Bari, a man with a volatile temper, was sent by the Congress to organize labour in Jamshedpur. He revelled in rousing labour in a language which he felt they could understand. But when it came to responsible negotiations he made life very difficult for the management. After Professor Bari’s death, Michael John took over and under his responsible leadership labour received many benefits and the company enjoyed an era of industrial peace.” – From The Creation Of Wealth by Russi M. Lala, Director for 18 years of the Tatas’ premier trust, Sir Dorabji Tata Trust.

“Everything implies a universe,” wrote the Argentine writer, Jorge Luis Borges. Before going on to other things, let us examine the words of R. M. Lala in the light of Borges’ statement. Lala implies that Professor Bari was irresponsible in his role as the leader of Jamshedpur’s steel workers and hence the management found it difficult to work with him. On the other hand, Michael John who came to succeed Professor Bari was a responsible leader who secured benefits for the workers in an atmosphere of industrial peace.

If the testimony of such an experienced trade-union activist as R. L. Verma is to be believed, the trouble with Professor Bari lay not in his ‘temper’ or in his ‘language’ but in his steadfast refusal to be a management creature. His was a one-point agenda doggedly pursued, and that point was to ensure that the workers got their legitimate rights, be it wages, bonus, housing, medical and other allowances or working conditions on the shopfloor and in the offices. His universe had no room for self-interest in any form whatsoever; his universe was peopled by the workers who had reposed their complete trust in him before, during and after the ‘Quit India’ movement.

On the other hand, the universe inhabited by an increasingly ailing Michael John had room for compromise with the management. The more sick John got in the 1950s and the 1960s (Professor Bari died in 1947), the more tenaciously he clung to power, making himself vulnerable, a fact that did not miss the watchful eyes of the Tisco management. Another thing that happened in the meanwhile was the appearance of groupism within the Tata Workers’ Union – something unheard of in the days of Professor Bari. This was a development on which the management began to work to its own advantage. Very soon the culture of signing on the dotted line became an accepted fact of union-management relations. The practice of ‘negotiated’ settlement which saw the light of day under Michael John and later V. G. Gopal, who had once rebelled against John and came to be murdered many years later in the wake of intra-union rivalries, began as a tragedy and soon turned to farce.

This then, in brief, explains for the condemnatory tone of Lala’s words about Professor Bari and the enthusiasm he expresses for Michael John. In other words, the universe of rightful assertion is bound to collide with the universe of abject surrender. At the moment of writing, that surrender has taken on such pusallinimous colours that no one in Jamshedpur takes the Tata Workers’ Union seriously any more. For a mess of pottage, the leaders of the union are known to climb down to any level, so what if the rights of the workers are sacrificed at the altar of management demands. It goes without saying that this suits the management perfectly.

Mahatma Gandhi called Professor Abdul Bari ‘a king amongst men’ and ‘a prince among patriots’. Professor Bari never compromised on his principles and would brook no opposition when it came to securing the legitimate rights of the working class. So, it was a grave travesty that nothing was heard about Professor Bari’s exemplary life as a nationalist and labour leader when, in early 2004, the former President of India, A. P. J. Abdul Kalam, visited Jamshedpur to participate in what the Tisco management wrongly touted as “75 years of industrial harmony” in the company. Apart from the conspiratorial silence regarding Professor Bari, one could question the authenticity of the claim about 75 years of industrial harmony when as recently as 1958 there was a massive strike by the Tisco workers which was brutally suppressed with the complicity of the State terror machine.

No account of Professor Bari’s life and legacy would be complete without mentioning the fate of a piece of consecrated ground named after him in Jamshedpur. Bari Maidan, as it was called, was a part of the folklore of the city till some years ago when the Tisco management decided – as many old-time Jamshedpurians believe – to strike at the memory of the great man. Now, the significance of the place should be kept in mind. For almost half a century, all important public meetings, workers’ rallies, gatherings of activists would be held at the Bari Maidan. Dissidents representing different causes would descend on the place from time to time and in general give a fillip to the steel and engineering workers to think for themselves. Apart from paying homage to the man who did the most for Jamshedpur’s toiling masses, speakers would dwell on issues and ask questions that caused acute embarrassment to the Tatas in general and Tisco in particular. So, one fine day, the Tisco management simply gobbled up the Bari Maidan, bringing it within the premises of the factory. A high boundary wall was created around the Bari Maidan — all in the name of factory expansion and modernization. A classic case of corporate chicanery – Na rahega saap, na bajega basuri ! (No irritant left, so no need to contain it.)

Perhaps the most outrageous part of the incident is that neither the local administration (meaning the Deputy Commissioner and down the line), nor the Indian National Trade Union Congress – the INTUC, to which Professor Bari belonged, nor the people at large put up any resistance against what can be truthfully described as a dastardly act of misappropriation of history. True, a crime had been committed, nothing less than a crime with the complicity of the State, but, come to think of it, can anyone erase history that easily? Perhaps, the Tisco management had thought that the legacy of Professor Bari could be marginalized, even rubbed out, but one likes to believe that history moves differently. The wheels of memory, of remembrance and consciousness, may grind slowly, but they grind all the same – it is just that many men and women do not seem to notice it.

Soon after the “blocking out” of Bari Maidan from public view, Tisco resorted to a piece of Machiavellianism that added insult to injury. It created a ‘new’ Bari Maidan in a neglected nook away from public view to take the sting out of public criticism, muted but not the less effective for that. No meetings are held there, children play games amidst weeds and bushes, and steps leading to the locked space gather animal excreta. It stands to reason that in course of time, the new Bari Maidan will also come to be conveniently ‘consumed’ by the cannibalistic appetite of the factory. Lo and behold, there will be no public space named after the fighter and visionary. And the company that habitually claims to be India’s most enlightened enterprise, will have had its way, in this as in every other instance in the steel city where not a leaf stirs, not a bird sings without the company’s consent.

The Asian Wall Street Journal of October 10, 1988, carried an article by its staff reporter, Sudeep Chakravarti, which could serve as a launching pad for any researcher of probity and courage wanting to go into the inner workings of Jamshedpur, the factory and the settlement. Although the article, entitled ‘Indian city is run the Tata Iron way – pampered Indian city has its drawbacks’, makes no mention of Abdul Bari, it does refer to the 1958 strike by Tisco workers which was put down ruthlessly. The article says: “According to local labour leaders there is good reason to fear the company. They cite a 1958 labour demonstration in which hundreds of protesting labour unionists were shot by the State police and allege that the police were prompted to take such drastic action by Tata Iron.”

If there is one thing that the company is not prepared to put up with, it is criticism of its policies and practices in any form whatsoever. Its endless vilification campaign against Professor Bari flows from its fascist mindset that never ceases to dictate the terms of existence to one and all in and around Jamshedpur. So used has the steel behemoth got to the settlement’s culture of sycophancy that it is beyond its imagination that anyone could speak out against it. Chakravarti’s article says: “…the company is as liberal with its ire as it is with its funds. Tata pressures local newspapers and makes life difficult for employees and bureaucrats regarded as being insufficiently loyal. The dilemma for the people of Jamshedpur is whether Tata’s civic generosity makes up for its oppressive rule. Residents say it does – but not those who have been on the receiving end of the company’s wrath… Jamshedpur residents also talk of how officials in company-controlled clubs and charities are pressured to toe the Tata line.” To survive in Jamshedpur, one has to be a sycophant and the sycophancy “springs from a fear psychosis”, to quote Russi Mody, the former chairman of Tisco whose ignominious exit from the company is a matter of public talk in the city even three decades after it happened.

Talking of being ‘generous’ to friends and inimical to real or perceived enemies, it is necessary to mention the contrasting attitudes of the Tisco management to the memory of two former presidents of Tata Workers’ Union. On the one hand is the sheer vindictiveness with which the Bari Maidan was misappropriated, so that the younger generations may, presumably, be ‘spared’ acquaintance with the saga of an austere, honest and courageous Gandhian nationalist; and, on the other, is the telling spectacle of the Regal Maidan, a large space in the heart of Jamshedpur, being renamed after V. G. Gopal, a staunch friend of the Tatas who outdid even Michael John in his efforts to remain in the good books of the employer. But whatever designs the company may invent, there is no taking at least a section of the people of Jamshedpur for a ride; they know what is what. While they sneer at the mention of Gopal for whom they have invectives normally not used in parliamentary debate, they have nothing but heartfelt gratitude for the one who came poor from Patna and left this world even poorer after long years of selfless struggle on their behalf.

Shining lives such as Abdul Bari’s come to the fore when one recalls the words of the renowned scholar of medieval times, Ibn Rushd (1126 – 1198) : “A society is free and pleasing to God when no man acts out of fear of a prince or of hell, or out of a desire for reward from courtiers or in heaven.” Upsetting popularly accepted beliefs, an individual can at some uncanny moment of history outweigh an entire society. Such a one was Professor Abdul Bari who was, in his own area of toil, given as difficult a job to perform as the one that history entrusted to his political master, M. K. Gandhi. That the latter saw in him nothing less than ‘a prince among patriots’ is a testimonial uncontestably heavier and more lasting than the accumulated calumnies thought up by all the steel company’s men.

( Vidyarthy Chatterjee writes on cinema,society, and politics.)

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER