In 1992, a Canadian ecologist named William Rees coined the term “ecological footprint,” a measurement of how much any entity was impacting the planet’s ecology. A decade later, British Petroleum started promoting a new term: “carbon footprint.” In a splashy ad campaign, the company unveiled the first of its many carbon footprint calculators as a way for individuals to measure how their daily actions—what they eat, where they work, how they heat their home—impact global warming.

BP did not adopt the footprint imagery by accident. In the 30 years prior to the carbon footprint campaign, polluting companies had been using advertising to link pollution and climate change to personal choices. These campaigns, most notably the long-running Keep America Beautiful campaign, imply that individuals, rather than corporations, bear the responsibility for change.

“It was done so intentionally,” says Susan Hassol, director of the nonprofit science outreach group Climate Communication. “It’s a deflection.”

The universal adoption of the term “carbon footprint” hasn’t just changed how we speak about climate change. It’s changed how we think about it. Climate change has become an individual problem, caused by our insatiable appetite for consumption, and therefore a war that must be waged on our dinner plates and gas tanks, a hero’s journey from consumer to conservationist.

Yet the reality is that the future of civilization is being decided at a political and corporate level that no individual can impact. Just 100 companies are responsible for 71% of global emissions. Fossil fuel giants are funding climate change skepticism while simultaneously lobbying for tens of billions of dollars in subsidies. Big corporate names like Costco and Netflix are loudly committing to reduce emissions but unable to set meaningful targets or put plans in place. The Trump administration rolled back more than 100 environmental rules and regulations.

The same way that you give your child a toy to play with so you can finish your task uninterrupted, everyday citizens are busy changing out lightbulbs and buying electric cars while the true cause of global warming continues uninterrupted: a civilization dependent on fossil fuels. As Mike Tidwell, the executive director of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network, wrote in a 2007 op-ed, “every time an activist or politician hectors the public to voluntarily reach for a new bulb or spend extra on a Prius, ExxonMobil heaves a big sigh of relief.” A complete paradigm shift is needed—both in the way we conceptualize our individual climate impact and in the ways we calculate the emission impacts of those ultimately responsible: corporations and governmental systems.

One of the challenges with the carbon footprint measurement is how few of the factors an individual controls. Most of us have limited options for where we live, how far we have to commute to get to work, what kind of energy is available to heat our homes, etc. If we don’t own our home (and more than 30% of Americans don’t), we may not be able to properly insulate or install high-efficiency appliances. One research report from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology found that roughly one third of a city dweller’s carbon footprint is determined by public transportation options and building infrastructure. “We build our cities this way,” Hassol says. “It’s system change that’s really needed so that people have better choices.”

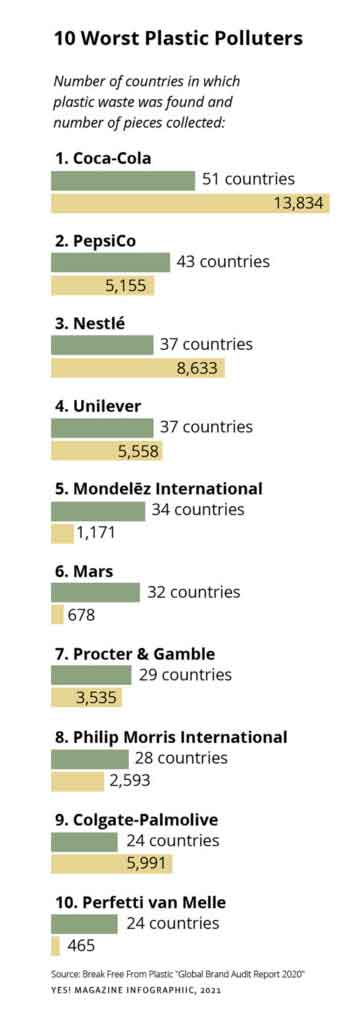

The inadequacy of our carbon footprint as a driver of change is painfully highlighted when you look at single-use plastics. Much attention has been given to how much plastic Americans consume (35.3 million tons per year, enough to fill the 104 million-cubic-foot AT&T Stadium in Dallas every 16 hours) and how each individual should be changing their behavior to help combat this waste. Everywhere you look, there’s a campaign to recycle more, or use metal straws, or bring your own bag to the grocery store.

In contrast, there are no public campaigns about the fact that packaging, an area where consumer control is limited, is the top driver of plastic production by a significant margin. The emissions impact of plastic manufacturing itself is rarely mentioned, along with the fact that much of our recycling still ends up in landfills. Some of the poorest nations are left to deal with hundreds of thousands of tons of soft drink bottles. The plastics are often just incinerated, creating serious environmental and health consequences. It’s a question as to whose carbon footprint is making a deeper impact on the environment: the family whose lettuce comes sealed in plastic (and who pays, not only for the product, but also for the waste collection and management services), or the company that is continuing to package food products in plastic materials, and then opting out of responsibility for their disposal.

Even if we just wanted to measure individual impact on climate change, the carbon footprint falls painfully short: “The current concept of a carbon footprint is too narrowly drawn,” Hassol explains. “It’s only the things I’m actively using and doing in my personal life and it doesn’t draw on other actions that are perhaps more important in the big picture as far as addressing climate change.”

For example, the average American has a carbon footprint of 16 tons. The average individual footprint globally is 4 tons. But that calculation doesn’t include who you vote for, how you invest your money, who you work for (and how much you travel for work, versus for leisure), or how you talk about climate change and influence others to get involved. “All of that should be part of the way we conceptualize our impact,” Hassol says.

For example, the average American has a carbon footprint of 16 tons. The average individual footprint globally is 4 tons. But that calculation doesn’t include who you vote for, how you invest your money, who you work for (and how much you travel for work, versus for leisure), or how you talk about climate change and influence others to get involved. “All of that should be part of the way we conceptualize our impact,” Hassol says.

Instead of obsessing over a single metric, Cameron Brick, a social psychologist from the University of Amsterdam, says he urges people to have an ongoing and evolving conversation between themselves and their chosen lifestyle. “It’s not a single number, because anytime you pick a metric, then we will begin to game it,” he says. Instead, a minimal-carbon lifestyle is a process—one that involves community-building and continuing to make improvements over time, he says. “My lifestyle is not perfect either, but probably better each year.”

Hassol points out that one of the most important ways that an individual can impact emissions on a wider scale is also the hardest to calculate: social contagion. “When people do something, it affects others around them and their emissions,” she says.

Studies have shown that energy-related behaviors are heavily influenced by peer groups, even more than cost or convenience. A study in California showed that every time a solar panel was installed within a certain ZIP code, the probability of another installation in that area increased by 0.78%. Similarly, if you know somebody who has given up flying because of climate change, you are 50% more likely to also reduce your own air travel.

“Your individual footprint is not the full measure of your contribution because you’re encouraging other people through your personal actions,” explains Hassol. She recommends that people who want to do more should research community solar options and ways to buy into clean energy in their communities, and then publicize those options among their families, friends and social networks, in order to create that initial momentum for change.

But what could system change look like? For starters, using measurements that actually hold the decision makers responsible for their emissions impacts, for the entire lifecycle of their product or service. That might look like Big Soda being held accountable not only for the manufacturing and transportation of their single-use plastics, but also for each and every bottle that ends up in somebody’s recycling bin (Coca-Cola is the top producer of plastic waste in the world). The shift also might look like emissions information being printed on product labels and unbiased regulatory bodies certifying the accuracy of corporate emissions reports.

On the policy level, interest in a carbon tax is growing. The Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act was reintroduced in Congress this year (as Senate bill 984 and House Resolution 2238), and would force a temporary moratorium on virgin plastic production, require minimum recycled content, and ban some single-use plastic food service items. Many states already have some form of a producer responsibility program, where the producer of hard-to-dispose products such as paints, batteries, and other hazardous materials, must finance proper disposal. This creates an incentive to design reusable or less-toxic products.

When we shift the focus from changing consumer behavior to changing producer behavior, we see where true change happens: in corporate boardrooms and among political leaders. The irony of the carbon footprint is that individual action does have the power to change the world, just not on the lightbulb and recycling level.

“This problem is too big to solve voluntarily one person at a time,” Hassol says. “We need to change the system and you have a role in changing that system.”

Emma Pattee covers topics related to climate change and feminism. Her work has been published in The New York Times, The Cut, WIRED, and others. She lives in Portland, Oregon.

Originally published in YES! Magazine

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX