In recent years, the Tamil cinema has seen a flurry of films mainstreaming Dalit narratives that bare the underbelly of a regressive caste driven society. As Dr. Biju, the Malayalam director of “Veyil Marangal” fame had posted on Facebook that the Tamil filmgoers, unlike their Malayalam counterparts, receive anti-caste narratives with great fervour and essential gravitas. Written and directed by T J Gnanavel, Jai Bhim is one such socially conscious film that has been riding high on praises from various quarters for bringing an important social issue to the fore. Immediately following its release on November 2 on Amazon Prime movies, the film’s popularity soared leaps and bounds beyond regional borders and those who endorsed the movie include some high- profile people like the CM of Tamil Nadu, M.K Stalin.

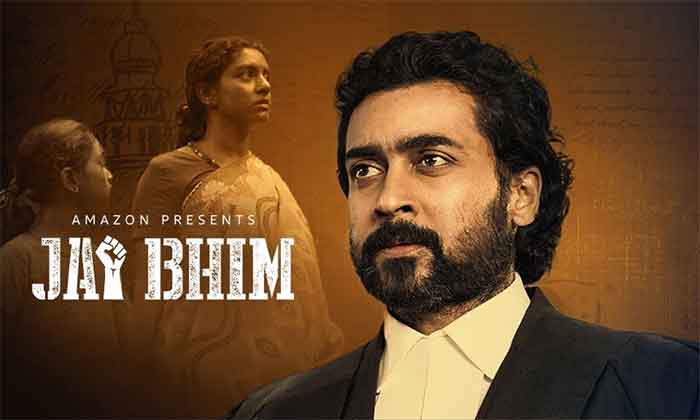

The film follows almost the familiar trajectory of prior anti- caste narratives in Tamil commercial films where caste atrocities and police high-handedness act as the leitmotif but what sets this film apart are essentially two features. Firstly, that this is a courtroom drama that showcases all important actions within the court and secondly, the deftness with which the director carves the character of Suriya as Advocate Chandru. Even as he capitalizes on the protagonist’s star value, he takes utmost care to not make him explicitly too loud or preachy but to operate on his measured silences and to leverage on his intense eyes. Suriya does this in an effortlessly exquisite manner that has won him many accolades. However, it is vis-a- a-vis Lijimol Jose’s stellar performance as Sengani that accentuates his performance. The raw Sengani, unlike Chandru, holds no bar on emotions. She wails at all the misfortunes that befalls her, yet the iron- like resolve with which she proceeds with her case is a delight to watch. She approaches Advocate Chandru who dons the mantle of a ‘saviour’ of the downtrodden and from then on, the character arc brilliantly executed by Sengani and the consistent tenacity of Chandru, both work in tandem making the narrative interestingly engaging. Suriya’s star value doesn’t eclipse the cause for which he strives, though with certain exceptions with regard to the BGM of Soan Roldan, that can be overlooked for the larger message that the film delivers.

The real-life inspiration behind the film is Justice K Chandru who led a legal battle during his career as a lawyer in 1993 championing the rights of a woman from the Irula tribal community of Cuddalore district in Tamil Nādu. This is a community of rat and snake catchers and since they belong to the Adivasi tribe, at the slightest pretext they are stigmatized as burglars who can be treated subhuman by the authorities. The starting scene itself is an exposé of sorts wherein the rogue policemen extricate the upper caste accused without any trial while the poor lower caste men are arrested at the slightest pretext, mostly with false cases foisted upon them, and made to stand apart in queue. Another sequence that acts as an extension of these arrests comes after nearly half of the plot where Advocate Chandru, along with the IG (acted brilliantly by Prakash Raj) goes to the village to enquire upon the grievances of the underprivileged and here we get the real answers for why these innocent people are picked by the police.

In a telling scene, the Leftist lawyer, Chandru is seen sitting on a chair, cross-legged, reading a newspaper and beside him we see the little girl Alli, acted by the talented Joshika Maya, mimicking his posture, perhaps with a better sense of pride, holding and reading another newspaper. By definition, this shot functions like a precise portrait of the inherent message of the movie, the Ambedkarite ideology, “Educate, organize and agitate”. Moreover, this scene has the substance to amuse the audience for the fact that it reflects possibly a novel attitude – how a child deserves equal respect from an adult.

Watching the film from the coziness of their homes, majority of viewers are jolted by its blunt depiction of police atrocities and the humiliation heaped upon the under privileged sections of the society. Arguably, it would have pricked the conscience of the elite (savarna) and intermediate castes’ viewers for whom the visuals serve more of a cathartic value and less of an artistic indulgence. That explains why Jai Bheem, despite being a powerful film, still falters upon the essential nuances of visual grammar. There is no character in the film that shows the grey shades of the human mind. Occasionally the film panders to the commercial trappings of going overboard by stretching and repeating the same harrowing scenes of torture and agony, thereby force-feeding the audience with pity and fear. Responding to such concerns, director T S Gnanavel has reiterated that this violence amounts to only half of what had occurred in reality. Yet, many viewers have confessed that they couldn’t continue to sit for more than half an hour watching blatant violence on screen.

Keeping aside such shortcomings, it is a commendable film for its graphical narration, theme, script and some terrific performances from its actors. It has insinuated a sense of urgency to end the structural violence against the marginalized communities. Unlike films like Visaaranai that displays passive submission to fate, Jai Bheem challenges the very system and bureaucrats and fights tooth and nail for obtaining justice. The film is a haunting watch but a don’t-miss cinematic experience.

Ms Smitha M is working as an Assistant Professor in English in Government Victoria College, Palakkad, Kerala. Her academic interests include African literature, Indian literature in English, World Literature, Gender studies, Cultural studies and Film studies. Her extra activities comprise writing poems, film reviews and book reviews. Her writings have been published on various online platforms like Learning and Creativity-Silhouette, Culture Flash, Countercurrents, Fasihi Magazine and The Ether Euphony.” She has been selected as one among the 159 poets round the world to be included in an international publication titled “Paradise on Earth.” She has scholarly essays too, published in books as well as in online academic journals.

Email: [email protected]