In the early days of World War II, activism was in a state of suspended animation on the political front in India. Nearly the whole of the Congress leadership was in jail and their followers were lying low. British forces had suffered reverses everywhere; they had been driven out of Europe and thrown out of their far Eastern possession. France lay supine, and northern and Eastern Europe were crushed under the heels of Nazi Germany. Japan had dislodged the Dutch from Indonesia and the French from Indochina. Hitler had signed a nonaggression pact with Russia. But determined censorship laws kept India in the dark.

Subhash Bose escaped from the prison in Bengal and had made his way to Germany, where he met Hitler and in exchange for a promise of independence of India had pledged his support for the Axis powers. Ref 1. He had gone on to Japan and made a similar deal with the Japanese leaders and had subsequently organized an Indian National Army from the ranks of Indian prisoners of war.

The Japanese were at the doorsteps of Bengal. The British, according to most independent observers, had let the province slide into the grip of a massive famine. Millions died of starvation.

Alienation of Indians to the British had reached new heights and was exhibited whenever it could be. Josh Maleehabadi, by popular acclamation hailed as Shari-e-Inqilab — Poet of the revolution, announced that he had written a new poem and invited people for a public recitation. Tens of thousands flocked to the poet’s home in Lucknow. Not many among them understood plain Urdu, much less the highly stylized poetry, but they went wild with passion when the poet declaimed the opening line. “Salam ai Tajdaar-e — Germany ai Fateh-e-Azam” — “I salute thee, holder of Germany’s crown and conqueror of the world.” The police expeditiously whisked the poet away to jail.

Subhas Bose advocated militant resistance to the Raj. Elected to the presidentship of the Congress, he antagonized Gandhi and got elected to a second term against the latter’s wishes. He was the last one to be able to do so. Gandhi forbade leading members of the party to serve in the executive committee. Frustrated, Bose resigned. Ref 1.

Public opinion in the US was either neutral or sympathetic to the Nazi creed. Hitler was actually quite popular among the “red necks” or unsophisticated rural population, and many Americans were of German descent. A majority of Americans hoped that the Europeans would cut each other up. Thousands of Japanese immigrants lived peacefully and productively in the United States.

Ref 1.Churchill and Roosevelt were apprehensive that Germany would become a real world power and rival their position in the increasingly global economy. Between them, they managed to entangle the United States in the war.Ref 1.

With a massive infusion of American arms and men into Europe, and with startling resistance of Russians, whom Hitler, casting aside all considerations of the solemn non-aggression treaty, had attacked preemptively, the tide began to turn in favor of the Allies. Churchill, who presided over a national Government, realizing that Britain would no longer have the will or the strength to hold on, acceded to the demand of his labor party colleagues to settle the “India” question. Loud mutterings that the 1943 famine in Bengal was contrived were frequently heard. Ref 2.

A cabinet mission was sent to India to negotiate with the leaders of public opinion in the country. Congress leaders were released for the parleys.

Jinnah had, in the mean while, taken full advantage of the absence of congress leaders from the scene, and had consolidated his hold on the Muslim imagination. Reeling under relentless pressure from their own rank and file, leaders in Muslim majority provinces, who had for long evaded Jinnah’s reach, had to accept his dicta. In any case the Congress had vowed to abolish the feudal system. It was an existential issue for the feudal landowners.

Jinnah now negotiated from a position of strength. The Congress had to concede the status of sole spokesman of the Muslims of India to him. Protracted negotiations followed. Jinnah achieved his long sought after aim of parity between Muslims and Hindus in a federal India. The cabinet mission presented a plan with a federal government in charge of defense, foreign affairs, communication and currency. The country would be divided into three wings, (a) the present Pakistan plus Indian Punjab and Kashmir, (b) Bangladesh plus Indian Bengal and Assam, (c) the rest of India. Provinces had to stay in their wings for the initial ten years. After that period a referendum could be held to determine if the constituents units wanted to stay in the wings or coalesce with other units.

- Churchill had a US ship torpedoed in the mid-Atlantic and a US airplane shot down off the coast of Spain and put the blame on Nazi forces. Roosevelt, in his turn, seemingly ignored intelligence of the impending assault on Pearl Harbor, leaving the ships in port (albeit with most of the crewmen safely ashore), which the Japanese shot like sitting ducks. He thus won a propaganda victory and was able to garner public support for participation in the conflict and to persuade the US Congress to declare war.

2 It was widely believed in India that, apprehensive that Bengal might fall to Japan, the colonists deliberately created problems in the food supply so the former would be blamed for it.

The Congress objected to the denial of choice to provinces to opt out but after a lot of wrangling signed on to the proposal. The Muslim League did too. A federal cabinet was to be formed. The Muslim League stuck to its assertion that it represented all the Muslims of India and should be allowed to nominate all Muslim members of the cabinet. Represent as it did a considerable number of Muslims, the Congress would not accept that and forgo claim to its secularnationalist status.

The Viceroy went ahead with cabinet making, with the understanding that if and when the Muslim League changed its mind, it would be offered at least two major portfolios. The League, left out in the cold, agreed to join under the face-saving formula that they would be able to nominate a nonMuslim member of the cabinet. The League wanted the Home (control over police and security agencies) and Defense ministries. Patel would not relinquish the Home Ministry. Nehru had given Defense to a Sikh leader, Sirdar Baldev Singh, whose support was critical, as other Sikh leaders, especially Master Tara Singh, were flirting with Jinnah. Being a novice at governance, Patel urged his party to offer the Finance portfolio to the League. Nehru and the rest of the congress high command, equally innocent of administrative experience, went along. Jinnah nominated Liaquat to head the League part of the cabinet. Unsure of his skills in finance, he demurred, but was reassured by two Muslim finance officials, Ghulam Muhammad and Chaudhury Mohammad Ali.

Liaquat stunned the nation’s industrialists by presenting a truly “progressive” budget, levying high taxes on capitalists, most of whom were Hindus. The Congress was the political wing of Indian capital, bankrolled by it and beholden to it. They howled in anguish. Liaquat relented a bit, but put the onus of concessions to the capitalist class squarely on Congress’s, especially Nehru’s, head. Patel, woefully moaned, that he could not even appoint a peon without Liaquat’s approval.

Congress leaders floundered and finally came to the conclusion that they could not coexist with the Muslim League ministers. And post independence, if Jinnah deigned to consider an office, independence would not be worth the trouble. That presumably made Nehru, the Congress president, declare to a press conference that the sovereign constituent assembly of India would not be bound by any pre-existing agreements and would frame a constitution based on the will of the majority. This was a flagrant denial of the letter and the spirit of the tripartite acceptance of the cabinet mission plan. Jinnah took the bait, fell into the trap or as some would have it, acting in character, pounced on the blunder of his opponent. He issued a statement that a party which, when not even wielding real power, could so blatantly repudiate agreements that had been so solemnly concluded, obviously could not be trusted to abide by them when it had the actual reins of government in their hands. He withdrew his acceptance of the cabinet mission plan.

Reacting to the Congress’s demand that it being the majority party, all power be handed over to it, Jinnah gave a call for direct action and exhorted his followers to observe a day of peaceful protests. Muslims all over India took out processions. In Calcutta, there was widespread rioting. Suharwardy, the Chief Minister of the province, a Muslim League nominee, was widely accused of presiding over the mayhem, or at least not taking effective measures to control the situation. But Jinnah had impressively exhibited his street power, exulting that it was not the Congress alone which could mobilize the masses.

The viceroy Lord Wavell, former commander in chief of the British Indian Army, a man of undoubted integrity and respected by all parties, was mindful of the support Jinnah had given the British in their hour of peril. He flew to London to present the case for partition of India.

The labor party had won the 1945 general elections in Britain, and Atlee was the new Prime Minister. Several members of his cabinet had close ties with Nehru. The Congress, accusing him of favoring the League, had demanded Wavell’s head. Atlee told Wavell that he accepted the idea of partition of India, but did not think the latter should preside over it. According to impartial observers, the dismissal was patently unfair. The viceroy was managing quite well. Churchill, now the leader of the opposition, asked Atlee not to show disrespect to a war hero. But the latter wouldn’t budge.

Atlee chose a new viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, a member of the British royal family, admiral of the royal navy, former head of the allied forces in South Asia, and as some would have it, Nehru’s nominee.

Ref 1. Mountbatten had met Nehru in Singapore during the final stages of the war and been impressed by him. His wife had fallen in love with Nehru. Her husband was quite “understanding.

Ref 2. Mountbatten’s partiality was to cross all bounds of integrity. He showed all the plans to Nehru before making them public and let the latter change them at will. He retained a Hindu Civil servant V.P. Menon as his political secretary. Menon was in Patel’s pocket and divulged state secrets to his boss on a regular basis. Ref 3.

It turned out to be a singularly poor and tragic choice. The man had no experience in civil administration. He was arrogant, vain, and overly conscious of his royal connection. He had little foresight or insight. He was much more concerned with his place in history than the fate of Indians.

Ref 1 There is of course no documentary evidence that Atlee was swayed by Nehru’s opinion, but it stands to reason that he would listen to his cabinet colleagues.

Ref 2 She was to have a lengthy affair with Nehru, as shown by her posthumously-released correspondence. The liaison would have grave and deleterious effect on Jinnah and Muslim league. Please refer to Mission with Mountbatten by his military aide Alan Campbell Johnson. Ref 3 Ibid.

On arrival in Delhi, declaring that in the first instance he simply wanted to get acquainted with them, he invited Gandhi, Nehru and Jinnah for informal talks. Jinnah famously told him that he would agree to a discussion only on the condition that he be regarded as the sole representative of the Muslims of India. Ref 1. Mountbatten told Jinnah that the meeting was only to give both an opportunity to get to know each other better. They developed immediate antipathy. The meeting lasted over an hour; Jinnah would only respond in monosyllables. Mountbatten told his assistants that he would rather have several meetings with Gandhi and Nehru than one with Jinnah.

Lengthy negotiations ensued again. Mountbatten had to concede the demand for partition of India, but he told Jinnah that if the country could be divided, provinces could be too and if Jinnah would not agree with the idea, he would simply hand over power to the congress and be done with it. Conscious of his fast deteriorating health, and certain that his assistants would not be able to withstand the combined onslaught of the British and the congress, he agreed to a “moth eaten Pakistan” Ref 2 .

Now, the small man that he was, having been thwarted in his designs to inaugurate a united independent India, Mountbatten decided to leave a veritable mess. Transfer of power was planned for June 1948. In March 1947 he advised the British government to bring the date forward to August 1947, otherwise, he claimed, the situation would get out of control. Civil war might break out. The loyalties of Indian soldiers would be sorely tried. British soldiers, too few and too tired, would not be able to cope with the situation. The cabinet had no choice but to accept his plan. He chose August 15, 1947, the date he had accepted the surrender of the Japanese army two years earlier, as the date of transfer of power into Indian and Pakistani hands.

Mountbatten, willful, unmindful, unaware, and not caring much for the consequences, delayed announcement of the boundary commission awards till two days after Independence. Ref 3 On Independence Day hundreds of thousands did not know which country their home was in. Officials had no information either. Such intricate business as dividing a country which had been one political entity for centuries would tax the skill of an experienced and seasoned administrator. Mountbatten, devoid of any such attributes, set unrealistic deadlines and proceeded with haphazard, disjointed and disorganized partition of the country, government and assets. He charged a boundary commission, the leader of which was unfamiliar with topography, with demarcating a line of control between India and Pakistan. It was a scuttle. Ref 1 Ibid.

2 Jinnah, on being shown a map of the future Pakistan, with Hindu majority areas, hived off the Punjab and Bengal, so described the country.

Ref 3. Please see Jinnah, Pakistan and Islamic Identity by Akbar S. Ahmad and The Sole Spokesman by Ayesha Jalal. India and Pakistan.

Mountbatten still harbored ambitions of staying on as the governor general of both countries. Nehru, cognizant of the advantages of keeping on the right side of the British government which still controlled all the levers of authority, readily offered the job to him. Jinnah rejected the feelers, claiming that his people wanted him to be the first Governor General of Pakistan. Mountbatten threatened Jinnah that it would have an adverse effect on Pakistan, but Jinnah would not budge. He sought advice from the British prime minister, who urged him to stay on as Governor General of India alone.

Whether Jinnah had spurned the advances of Mountbatten because of vanity and arrogance or, as he told his confidants, because he wanted, right at the beginning, to claim an unquestioned independent status for Pakistan, one will never know for certain. The fact that he was terminally ill may have been the determining factor in his decision. Whatever the reason, it was to have a far reaching and grievous effect on Pakistan’s fortunes.

Patel and Nehru (and, I suspect, Gandhi) were confident that Pakistan would collapse soon. There would be no other rational reason for Gandhi to change his stance abruptly and acquiesce to the idea of partition which previously he had vowed would happen only over his dead body. Patel is on record making a public speech that it would be only a matter of days, weeks, or at the most months, before Pakistan would collapse; they would go down on their knees to be taken back into the Indian Union. Only Azad, among the top Congress leaders, remained steadfast in opposing partition. Azad and Nehru were very close. Nehru probably did not take Azad into his confidence. Being acutely conscious of the latter’s sensibilities and lack of guile, he also may have wanted to spare his friend the Machiavellian designs of Patel. Azad had been the president of the Congress from 1940 to 1946. He would have been the automatic choice for the office of the first Prime Minister of India. But that was, under the circumstances, untenable. Muslims had got Pakistan. One of them could not be the PM of India too; such was the overwhelming sentiment. The party machine wanted Patel to succeed to the office. Azad offered to resign, but told Gandhi that he would not, till he was given solemn assurance that Nehru would follow him.

To hasten the collapse, Nehru and Patel withheld Pakistan’s share of the joint assets. Mountbatten aided and abetted them. The patently lame excuse they gave was that Pakistan would use the funds to wage more effective aggression in Kashmir. And collapse it would — it did not even have funds to pay salary to government servants — if the Nizam of Hyderabad had not come to the rescue. Reputedly the Bill Gates of his time, he gave Pakistan two hundred million rupees (equivalent to about $150 million at today’s value).

Once Pakistan became a going concern, Gandhi went on a hunger strike to force India to hand over Pakistan’s share of assets to the country. I would not like to give an impression that I am attempting to belittle Gandhi Ji or imputing immoral motives to him. He had put his life on the line and toured the riot torn provinces of Bihar and Bengal, alone, without any protection whatsoever. In the immediate aftermath of partition he had gone on a hunger strike to force a reluctant Patel to offer security services protection to the Muslims of Delhi. He had undertaken a fast unto death so the wretched of the wretched, the untouchables, would be conceded equal legal status. Finally he was assassinated for favoring Muslims in 1948. All I am saying is that he was a pragmatic politician who would sacrifice friend and foe alike for what he considered a “higher” cause.

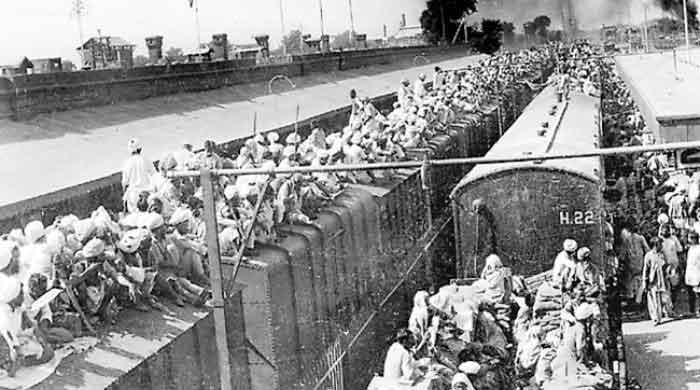

Post partition, starving refugees in untold millions, physically and mentally battered, destitute, and possessing only the clothes they wore, often carrying disabled elders and sick children on their backs, flooded into devastated towns and villages of the “moth eaten” land of the faithful. Millions more, in no better shape, moved to the other side. India had a functioning government and was blessed with more geographic depth to accommodate the refugees. Pakistan was bereft of any infrastructure, with its administration in complete chaos, and businesses, industry, schools, and hospitals paralyzed. The law and order situation was fast deteriorating. British police and other civil service officers, from provincial governors and heads of the secretariat down, lacked direction and focus. Further, they were incensed that Jinnah had rejected Mountbatten’s overtures to be asked to become the Governor General of Pakistan. The ones lower in hierarchy openly and gleefully witnessed the collapse of normal life.

India under Britain had two administrative divisions. Most of the country was ruled directly by Britain. About one third of the country comprising princely states was ruled through hereditary princes. The fiction of the princes having ceded certain discretionary rights to the paramount power was maintained. A British resident was, on paper, an “ambassador” from the mother country, but in effect supervised the state administration. The treaty agreements included a provision that if and when the British crown surrendered its paramount status, the ceded powers would revert to the princes. The Deputy Commissioner of the area supervised smaller states. If a small to middling ruler did not toe the line, he was easily replaced by a more amenable relative or the state could be taken over by the Court of Wards.Ref 1. There were literally hundreds of states ranging in size from Hyderabad, which was slightly bigger than France with its own currency, police and armed forces, to virtually those of the size of a village. Kashmir was the second largest state. Ref My Nana (mother’s father) worked for the system and was highly respected by the rulers. In addition there were tiny Portuguese and French possessions, which did not fall in the equation of British-Indian negotiations.

The Independence of India act passed by the British parliament contained the provision that major rulers could a) remain independent b) accede to India c) accede to Pakistan. The legislation provided that the desires of the population were to be taken into account. The legally valid claims that unfettered sovereignty had been restored to the states were thrown overboard by the British government. Mountbatten did go through the charade of calling a Durbar of the native rulers and affirming that Her Majesty’s government would stand by them, but advised that reality on the ground dictated that they strike a deal with one of the succeeding governments. Most of the states, surrounded by Indian or Pakistani territory acceded to India or Pakistan. Hyderabad and Junagarh, both with a Muslim prince and largely Hindu population, decided to opt for independence. The Hindu Raja of Kashmir with Muslim majority among his subjects was wavering, and was negotiating with India as well as Pakistan. He could not make up his mind, and signed a standstill agreement with both Dominions. The dominant political party in Kashmir, with its fiery leader Sheikh Abdullah, favored India. In the event the Raja’s mind was made for him. Muslim Mujahids, drawn from the ranks of zealots and tribal elements, reinforced by irregular elements of Pakistan army, decided to force the issue. They marched into Kashmir. The joint force easily reached the capital, Srinagar and the trained members of the expedition captured the electric supply station and cut off power to the city. The Mujahids fell upon the city, looting and pillaging. Both overlooked the airport and failed to secure the only link India had with the state. The land link with India was closed due to winter conditions.

The Raja, now desperate, asked India for help. Nehru was uncertain of the legal position. Mountbatten advised Nehru to demand accession of the state to India as the condition of support. The Rajah agreed. Indian troops were airlifted to Srinagar and easily overcame the Mujahideen. Thus started the festering sore that has bled and debilitated both countries ever since. Pandit Nehru accused Pakistan of aggression and took the case to the UN Security Council. The council did demand that Pakistan withdraw its forces, but mandated a plebiscite to ascertain the opinion of the public. It also sent a UN peacekeeping force to keep the combatants apart at the cease-fire line.

Lahore had been the capital since the Sikh ruled Punjab. Ref 1 The Sikhs had deluded themselves into believing that the city would go to India. Though only 40% of the population, non-Muslims controlled 90% of education and health, 86% of industry and commerce and 75% of agriculture of the province. Ref 1 After the fall of the Mughal Empire, the Punjab and much of what is current Pakistan (barring Sindh and Balochistan), had fallen to the Sikhs. Please refer to The Other Side of Silence by Urvashi Batalia Chapter 3. The Sikhs had nearly as many holy sites in the western as in the eastern districts of the province. They would have been better off, many adherents of the creed came to believe later, if they had joined hands with the Muslims.Ref 1 Non-Muslims could not move to Indian Punjab overnight. Muslims could not go to Pakistan immediately, either. There was no one to advise them, much less to help them. People trickled to the other side in caravans which were pounced on by gangs on either side who murdered, raped and abducted women and children — for the greater glory of their religion. The military “genius” Mountbatten had not taken time to organize escorts of soldiers for the caravans. About a million lives were lost, over ten million displaced, women in the hundreds of thousands were abducted, raped and often burnt alive after the outrage. Dozens of trains with all the passengers dead, often cut into pieces, driven by a British conductor, would arrive in Lahore (Pakistan) or Amritsar (India), triggering further massacres. Indian and Pakistani leaders could only look on helplessly, the liberal ones repentant that they had not come to an agreement with each other, the zealots swearing vengeance. There was not a word of apology from Mountbatten for the largest carnage in human history perpetrated by civilians because of his stupendous mistakes and mindless haste in partitioning India. There was conflagration in other places too. Delhi was aflame. With no protection and little escort, at the very risk of their lives, Nehru and Maulana Azad and other ministers toured all precincts of Delhi.

The Maulana made a memorable speech to the Muslims who had sought shelter in the Red Fort. Bihar, parts of UP and Bengal exhibited examples of unprecedented bestiality. Ref 2.

India was passing through its own period of turmoil. Besides the constant threat of the Hindu–Muslim tension breaking into open warfare, all too often provoked by rumors of cow slaughter spread by miscreants, the authorities had to deal with sharnarthees — refugees — from Pakistan who, though concentrated mostly in the Indian Punjab and Delhi, had also spread all over northern India in substantial numbers. They were a generally enterprising lot and quickly established stalls of food, groceries and general merchandise on footpaths and in parks. Residents and shopkeepers of the posh area, Aminabad Park in Lucknow, were not happy with the situation. Out of sympathy with the displaced persons they refrained from protesting, initially, but gradually became vociferous in their complaints. The park was the pride of the city. People used to have picnics and children played there in the evenings and on Sundays. It was dotted by Qulfi and lassi shops. Ref 3

Ref 1. During later insurgencies in India they would join hands with Muslim Kashmiri rebels.

Ref 2 Please refer to his collected speeches.

Ref 3. A delicious ice cream and yogurt drink, very refreshing in the sultry heat of Indian summers.

There were linguistic and cultural problems too. People in UP addressed each other as Aap. Ref 1. Sindhis were used to calling each other “Sain.” We called beggars Sain. Among the Punjabis “Tusi” was a mark of respect. With us it sounded like a corrupted version of “Tum,” an expression indicative of familiarity. Many a quarrel, sometimes ugly, would erupt between the natives and newcomers on such seemingly trivial issues.

The loss of wartime jobs had led to severe unemployment. At one point there were all India students, teachers, and trade union strikes simultaneously. Municipal and Civil services had been pushed to the breaking point. Refugees from Pakistan were living in Railway stations, parks and footpaths. Shantytowns had mushroomed in the outskirts of all cities. Governments, federal and provincial, were unable to cope. As though Hindu–Muslim conflicts were not enough, there were Muslim sectarian Shia–Sunni, Hindu upper and lower caste, immigrants and native, rich and poor, worker and capitalist conflicts.

There were bizarre incidents too. Pandit Nehru, triumphant after a nonaligned conference in Bandung, Indonesia, arrived in Lucknow and was greeted by black-flag-waving crowds of refugees. This was a novel experience for him. Visibly upset, he asked UP chief minister Panth to explain. The man, terrified out of his wits, expostulated that they were demonstrating against the UP government for not being able to provide jobs and shelter.

Expecting the usual mass adulation when he started to speak in the public meeting the next day, he was instead met by unruly crowds chanting anti government slogans and again waving black flags. It must have been a shock to a person who had emulated Jinnah and called his admirers uncouth rustics during a countryside tour. Ref 2 The whole scene was clearly visible from the balcony of the house facing the Park where I was staying. He started, “I went to Indonesia,” only to be interrupted with hoots and catcalls. Annoyed, he turned to Panth, who gave him the excuse that the mike was not working. Workers scrambled to sort out the mike. He started again. The crowd erupted again. Now Panth blamed the gaslights hanging in front, obscuring the public view of him. People could not see Pandit Ji. The lights were removed. The clamor did not diminish. At this point Nehru lost his composure completely. Shouting at the top of his voice, he asked if they could not hear or see him, or was it an exhibition of insolence. He went on, targeting refugees, teachers, students, policemen and trade unions in turn, threatening to have refugees who had despoiled Lucknow’s historic gardens and parks thrown across the Gomti (a local river), and to close schools and factories. The teachers had turned into gangsters, students had not learnt that they had won independence, workers that they were no longer serving the Raj and policemen had been very good at arresting him and clearing the way for the white masters but were unable to get him from the airport to the governor’s house without harassment. The police launched into the crowd, only to be told not to behave like fascist animals. He was working day and night to enhance the image of the country internationally. He was doing his job, and did not want an expression of gratitude. He went on ranting and raving. Total silence ensued. He smiled enigmatically and started again “I went to Indonesia” and the public terrified out of their wits, wouldn’t even clap and applaud, when he regaled them with description of international meetings and events where he was feted and India so highly regarded.

Ref 1 People in the north of India addressed elders and those they were not familiar with as “aap”; it denotes high regard. “Tum” is you.

Ref 2 On a motor tour of Indian Punjab some peasants stopped his car and asked him to make a speech. Incensed, he shouted rude remarks. The crowd responded with, “Pandit Nehru ki Jai” — long live Nehru. I read it in a newspaper in 1950.

While analyzing the early post-independence period, one must not overlook the fact that the public and private persona of most of the people and some of the leaders were at a wide variance with each other. The first Indian president, Rajendra Prasad, though he had sworn to uphold and defend the Indian constitution, which was and remains secular in spirit and word (not since Modi Raj), and though he was by convention bound to follow the prime minister’s advice, decided to go to the consecration ceremony of the rebuilt Somnath Mandir against the express and public advice of Nehru. He covered himself with the fig leaf that he would attend the ceremony as a private citizen. He was, however, accorded the full state protocol.

There was overt discrimination against Muslims in jobs, school admissions and award of private and government contracts. If a member of the family had migrated to Pakistan the property of all members was confiscated. Muslims could not rent houses in choice localities. They were taunted and asked openly as to why they did not go to their beloved Pakistan? It was a Hindu Raj now. They better conform as the Hindus had done to Muslims norms when the latter had ruled India. In the famed Bollywood movie Garam Hava, the incomparable Balraj Sahni plays the lead role of a Muslim whose elder brother has left for Pakistan. The house they lived in was held in the name of the departed head of the family and was taken over by the government and they were forced to leave. A poignant scene depicts the fate of the family. The mother hides herself in a chicken coop in a futile attempt to escape the government functionaries.

Independent India ushered in a rather radical change in the school system. In the ninth grade one could opt for Science, Arts (humanities) or Crafts (trades) groups. I chose the Science group, which did not have history, geography or drawing, all the subjects I detested. My school was highly competitive and strived to get one of its students among the top sixteen positions in the UP Education board examination once about every three to four years.Ref 1 Our teachers gave free coaching to a select group of students. My mathematics teacher nominated me to the group. He was a tall and fair Kashmiri Brahmin, immaculately clad in a kurta and dhoti1 and sported a tilak (caste mark) on his forehead, but did not have a bit of communal prejudice. Ref 1. He advised me that I should learn Hindi because, given the prevailing linguistic chauvinism, answers/essays written in the national language would be given higher marks than would attempts in English. I had been brought up in an English medium of instruction. I protested; this was not fair. My teacher, as good a philosopher as any I have met, told me that life was not fair. Ref 1. About 165,000 students took the 10th grade examination every year.

I was elated to be included in the select group. But it was not to be. In the first week of May 1951 we, along with the families of my Nana’s brothers, embarked on a long and circuitous journey to Pakistan. We alighted from the train at Muna Bao, the last station on the Indian side, tired but exhilarated by the idea of finally being within reach of the land of the pure and unlimited promise. We were herded into an open flat-bed truck, which drove us to the still open border. Fortunately it was only a short journey. We were off loaded on the Indian side and walked across to the Pakistani soil amid loud slogans of “Allah o Akbar” (God is Great) and “Pakistan Zindabad” (long live Pakistan). Pakistani truck drivers were there to greet us. We eventually arrived at a railway station named Khokrapar, which was a veritable tent town. We were lucky enough to find room under a huge water tank, which was a great relief in the harsh desert summer. We had to camp in the open air for several days waiting for the once-a-week special train to our next stop. We eventually arrived in Quetta which was unlike any city we had lived in before. It was cold even in May; the temperature would not go above the mid-sixties at midday and would drop to the forties at night. We were, of course, comparing it to what we were used to in the UP province of India, over 110° during day time and in the 80’s at night. The city was clean; the roads were actually washed and swept twice a day. Fruits and groceries were much cheaper than they were in India.

But the most astounding difference was in the price of fruits. In India grapes were a delicacy. Only the rich could eat them, or apples for that matter, every day. They were offered wrapped in cotton wool at the fruit stalls. In Quetta they were dumped unceremoniously on carts as potatoes were in India, for about sixteenth of the price. We gorged ourselves on grapes and apples and developed indigestion.

The first house we rented had a surprisingly low rent. We were soon to discover the reason why. Among Indian Muslims when people move to a new accommodation, whether bought, built or rented, they have a gathering in which poems praising the Prophet of Islam are recited. It is called Meelad Sharif. Neighbors always join in and bring offerings of sweets. At the end of the proceedings Koranic verses are recited over the sweets. This is called Fateha. At the end of the Fateha there is a bit of socialization and small talk and sweets are distributed to all. Well, we had a very colorful party and the ladies of the neighborhood sang lustily and in good voice and tune. They were well made up and good looking, too. It turned out that my father had stumbled upon a mohalla1 of singing and dancing women. To my dismay, we moved again within a few days to a drab and ugly location where no female could be sighted for all the gold in the world. It was a terrible letdown.

Ref 1. A waist-length shirt and intricately bound loin cloth was the typical dress of Brahmins, the priestly and academic class of Indians.

Bio:

I was born in Dewa Sharif, UP, India in 1939.

I went to school from the fourth to eighth class in Gonda, UP and the 9th grade in Jhansi, UP, India.

We moved to Quetta, Pakistan and went to school for the 10th grade and intermediate college in the same town.

I was in Karachi University 1954-57, then Dow Medical College 1957-62. I Was in the National Students Federation from 1954 to 1962, trained in surgery in the Civil Hospital Karachi 1962-65, proceeded to England 1965 and trained in General surgery and orthopedic surgery till 73, when I left for Canada 1973-74, USA 1974-83, back to Karachi 1983 and built a hospital and went back to the USA in 1991, been in the USA since.

I retired from surgery in 2005.

I have worked in various HR and Socialist groups in the USA.

I have Published two books ,:”A Medical Doctor Examines Life on Three Continents,” and ,”God, Government and Globalization”, and am working on the third one, “An Analysis of the Sources and Derivation of Religions”.