Secular religions are hard to battle in terms of their misplaced assumptions. In some ways, they are even harder to fight than those based on mythical gods and superstitious foundations, many drawn from desert religions and sandy practice. ANZAC, the name of the Australian New Zealand Army Corps, hardly sounds promising as the basis of a religion. But since the needless, bungled operation in the Dardanelles that led to the slaughter of Australian and New Zealand Troops in April 1915, along with Turkish, British and French soldiers, the acronym has become scented, meaningful and powerful.

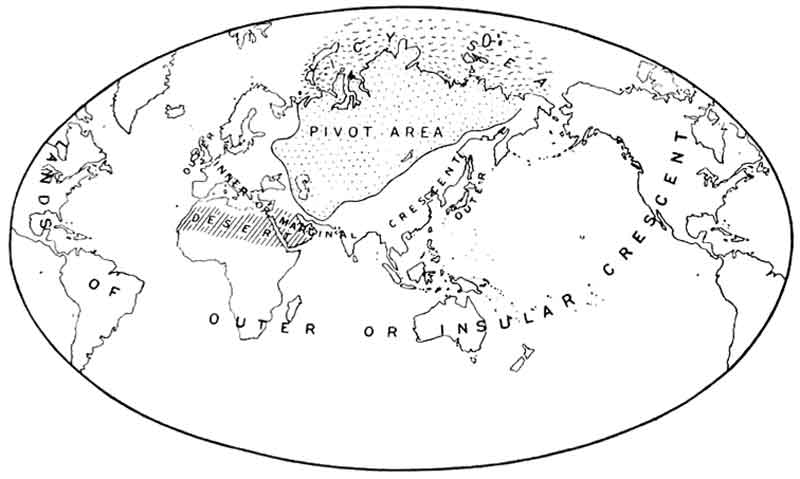

At first, it all seems rather daft. These troops, for the most part ignorant of geography and certainly of the myriad nature of European power relations, found themselves invading the Ottoman Empire in a chess move thought up by Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty. If the Ottoman Empire could be defeated, Imperial Germany would lose a key ally and be exposed on its flank. The mission failed in spectacular fashion and allowed Kemal Atatürk, future leader of secular Turkey, to distinguish himself.

During the First World War, Australia, with a population of 5 million, lost 62,000 men from 416,809 enlistees. Of those, 156,000 were wounded or taken prisoner. Over 3,000 men returned with tuberculosis and infected the population accordingly. The debilities of unrecognised shellshock reigned. This loss disfigured the country irreparably, dulling its optimism for reform. Australian communities turned inward, solemnly pouring savings into the creation of memorials across the country.

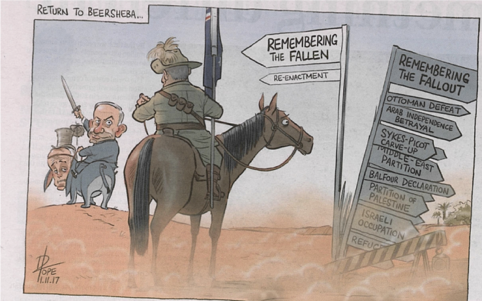

In its modern sense, Anzac Day has become, over the years, a parade for amnesia rather than reckoning, a ritual that rejects peace makers and conciliators in favour of the war mongers and undertakers. Disturbingly, the war mongers are allowed to skip merrily away from responsibility and celebrate character before the bullet and the shell.

Before Turkish fire, Australian soldiers were performed heroically and foolishly, adventurers in invasion meeting their demise before the ill-planned stratagems of their superiors. They were material for the empire, dolts for the cause, and discharged their roles well. They proved themselves suitably unthinking for the purpose of slaughter. “These raw colonial troops,” wrote British war correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, “proved worthy to fight side by side with the heroes of Mons, the Aisne, Ypres and Neuve Chapelle.”

The geography, loyalty, and circumstances of the Anzac Myth have troubled a number of Australian historians over the years. Marylyn Lake, in a public lecture given at Melbourne University’s free public series in 2009, was convinced that, “Australia’s identity shouldn’t be built on deaths in foreign fields.”

For Lake, the myth is an umbilical cord and retardant, a bar to the realisation of maturity. “The myth will remain our creation story until the nation is reborn, until we have the courage to detach ourselves from the mother country, declare our independence, inaugurate a republic, draw up a constitution that recognises the first wars of dispossession fought against indigenous peoples.”

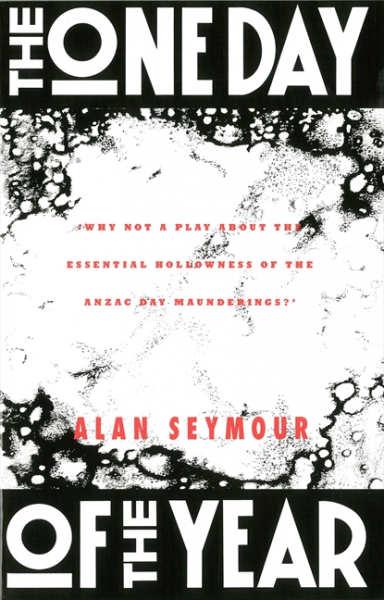

Anzac might have disappeared after seemingly running out of oxygen during the 1960s and 1970s. The divisive Vietnam War, with its various opponents in Australia, did not help. Then came the decades of revival, which also saw a scrubbing of complexity as to why Australians had ever volunteered in the first place for craven leaders guided by paranoia.

The Anzac myth became bound to notions of noble, stoic “mateship”, characterised by Peter Weir’s 1981 film Gallipoli. There were cruel and mentally vacant officers, and strikingly brave foot soldiers going to their death with an unquestioning valour. It was all about, as one implausible assessment goes, “brave soldiers keen to prove themselves as representatives of a fledgling nation, albeit one with an ignominious convict past”.

After 1996, during the years of the conservative Howard government, commemorations and war time lessons (or mis-teachings), became the norm. The Department of Veteran Affairs became a big fan of ahistorical instruction and hagiographical slurry. In padding and developing the myth, it was important to exclude a number of things. Anti-war movements vanished. The records of criminally incompetent generals and politicians were nowhere to be seen. The misogyny underlying the ideology could also be left alone.

Anzac traditions must, in their calling, resist self-examination and questioning. They are grotesque sentiments about mangled bodies and foolish decisions, sparing of military leadership and dooming the bloodied soldier. And if questions are asked, they often end up in the kind of execrable analysis that John Roskam of the Institute of Public Affairs offered in 2007. “War is often necessary,” he wrote with faux meaning, “and Australians have answered the call.” Even if the call is misguided or an incitement to unlawful conduct.

Roskam mentions the Iraq War, which began as an illegal invasion in 2003, and refuses to accept the awkward reality that Australian soldiers were inculpated by the operation. He can only offer a dottily pathetic observation: “One of the things that Anzac Day represents is the willingness of Australians to stand up for what they believe in.” How utterly noble.

Future unthinking Australian soldiers are likely to supply the raw material for more wars, including one in the Pacific. It is bound to be a foolish encounter, most likely led by the United States, and likely to result in few returns. Defence Minister Peter Dutton has been very happy to promise the laying down of Australian lives so that the US may feel secure, even if he is not entirely sure what the whole business about Taiwan is about.

The Australian Prime Minister of the day will be able, along with the cabinet, to say that it was all a job well done, presuming they survive such a conflict. And any moral twinge of sadness will be remedied by ceremonial, tear-soaked largesse, in addition the $498 million pencilled in for converting Canberra’s Australian War Museum into a militarist wonderland. The unaccountable will continue to send the unthinking into battle.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He currently lectures at RMIT University. Email: [email protected]