On April 25, along Melbourne’s arterial Swanston Street, the military parade can be witnessed with its bannered, medalled upholstery, crowds lost in metals, ribbons and commemorative decor. Many, up on their feet since the dawn service, keen to show the decorations that say: “I turned up”. Service personnel, marked by a sprig of rosemary.

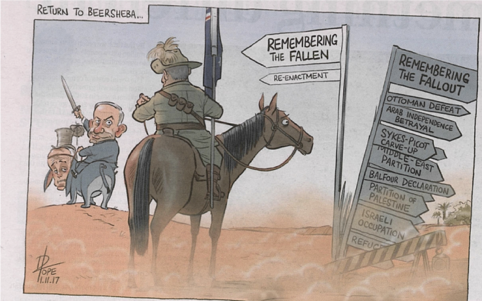

The greater the pageantry, the greater the coloured, crimson deception. In the giddy disruptions caused by war, this tendency can be all too readily found. The dead are remembered on the appointed day, but the deskbound planners responsible for sending them to their fate, including the bunglers and the zealous, are rarely called out. The memorial statements crow with amnesiac sweetness, and all the time, those same planners will be happy to add to the numbers of the fallen.

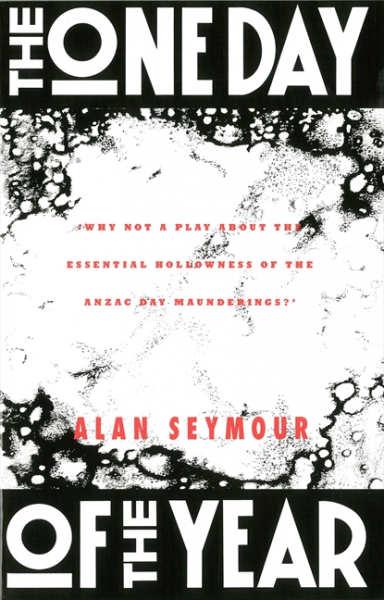

The events of April 25, known in Australia as Anzac Day, are saccharine and tinged about sacrifice, a way of explicating the unmentionable and the barely forgivable. But make no mistake about it: this was the occasion when Australians, with their counterparts from New Zealand as part of the Australian New Zealand Corps, foolishly bled on Turkish soil in a doomed campaign. Modern Australia, a country rarely threatened historically, has found itself in wars aplenty since the 19th century.

The Dardanelles campaign was conceived by the then First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, and, like many of his military ventures, ended in calamitous failure. The Australian officers and politicians extolling the virtues of the Anzac soldiers tend to ignore that fact – alongside the inconvenient truth that Australians were responsible for a pre-emptive attack on the Ottoman Empire to supposedly shorten a war that lasted in murderous goriness till November 1918. To this day, the Turks have been cunning enough to treat the defeated invaders with reverence, tending to the graves of the fallen Anzacs and raking in tourist cash every April.

For the Australian public, it was far better to focus on such words as those of British war correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett written on the occasion of the Gallipoli landings: “There has been no finer feat in this war than this sudden landing in the dark and the storming of the heights.” Ashmead-Bartlett went on to note the views of General William Birdwood, British commander of the Anzac forces at Gallipoli: “he couldn’t sufficiently praise the courage, endurance and the soldierly qualities of the Colonials”. They “where happy because they had tried for the first time and not found wanting.”

In March 2003, these same “colonials” would again participate in the invasion of a sovereign state, claiming, spuriously, that they were ridding the world of a terrorist threat in the form of Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, whose weapons of mass destruction were never found, and whose subsequent overthrow led to the fracturing of the Middle East. Far from being an act of bravery, the measure, in alliance with the United States and the United Kingdom, was a thuggish measure of gang violence against a country weakened by years of sanctions.

When options to pursue peace or diplomacy were there, Australian governments have been slavish and supine before the dictates and wishes of other powers keen on war. War, in this context, is affirmation, assertion, cleansing. War is also an admission to a certain chronic lack of imagination, and an admission to inferiority.

The occasion of Anzac Day in 2024 is one acrid with future conflict. Australia has become, and is becoming increasingly, an armed camp for US interests for a war that will be waged by dunderheads over such island entities as Taiwan, or over patches of land that will signify which big power remains primary and ascendant in the Indo- and Asia-Pacific. It is a view promoted with sickly enthusiasm by press outlets and thinktank enclaves across the country, funded by the Pentagon and military contractors who keep lining their pockets and bulking their accounts.

Central to this is the AUKUS security pact between Australia, the UK and the United States, which features a focus on nuclear powered submarines and technology exchange that further subordinates Australia, and its tax paying citizens, to the steering wishes of Washington. Kurt Campbell, US Deputy Secretary of State, cast light on the role of the pact and what it is intended for in early April. Such “additional capacity” was intended to play a deterrent role, always code for the capacity to wage war. Having such “submarines from a number of countries operating in close coordination that could deliver conventional ordinance from long distances [would have] enormous implications in a variety of scenarios, including in cross-strait circumstances”. That’s Taiwan sorted.

Ultimately, the Australian role in aiding and abetting empires has been impressive, long and dismal. If it was not throwing in one’s lot with the British empire in its efforts to subjugate the Boer republics in South Africa, where many fought farmers not unlike their own, then it was in the paddy fields and jungles of Vietnam, doing much the same for the United States in its global quest to beat off atheistic communism. Australians fought in countries they barely knew, in battles they barely understood, in countries they could barely name.

This occasion is often seen as one to commemorate the loss of life and the integrity of often needless sacrifice, when it should be one to understand that a country with choices in war and peace decided to neglect them. The pattern risks repeating itself.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He currently lectures at RMIT University. Email: [email protected]