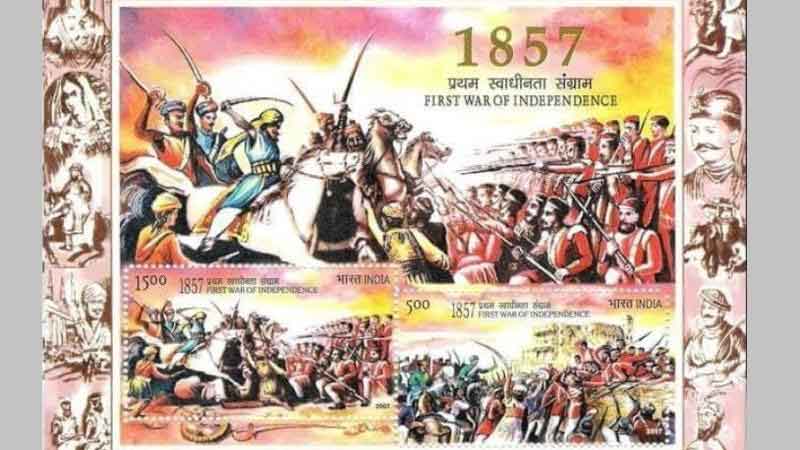

British rulers, historians, scholars, writers, folklorists have referred to the Rebellion of 1857 that started from Meerut on 10 May 1857 by different names. This diversity of nomenclature reflects people’s different attitudes towards the Rebellion. In the War of the nomenclature, the Rebellion has been described with derogatory terms such as ‘Ghadar’ by the Britishers on the one hand and ‘India’s First War of Independence’ by the Indians on the other. However, the word Ghadar, which was used as a derogatory term by the British, later acquired a respectable meaning for Indians. The organization formed by Indian revolutionaries in America in 1913 was named Ghadar Party. ‘Ghadar’ was the name of their mouthpiece as well. The title of the first Hindi novel based on the Rebellion, written after almost 75 years, also happened to be ‘Ghadar’. When Amritlal Nagar collected details of legends and memoires related to the Rebellion, he named that book ‘Ghadar Ke Phool’.

Apart from the nomenclature, there are many assumptions about the character of this rebellion. It is described to range from ‘feudal’ to ‘common people’s uprising’. There are various estimates regarding the number of people killed in the Rebellion. British records put the number of British people – including children and women – killed in the Rebellion at around 6000. The number of people killed on the Indian side during the suppression of the Rebellion and in the retaliatory actions taken by the British after the suppression is said to be from 8 lakh to 30 lakhs. It also includes the number of Indians killed in famines and epidemics associated with the rebellion.

The discourse of civilized-uncivilized and cruel-revolutionary can also be found in the writings of the historians of the Rebellion and the writers who wrote memoirs and fictional accounts based on various events and characters related to it. At the core of the Rebellion was merely a question of religious identity or was the rebellion fundamentally driven by the idea of nationality – this question has also been quite controversial and problematic. What I mean to say is that there is a whole world of arguments and counter-arguments laid out before us on the various aspects of the Rebellion.

In this article, written on the occasion of the 167th anniversary of the Rebellion, an attempt has been made to find out that at the core of the Rebellion was the idea of Indian nationality born out of the pain of subjugation. This attempt is made through a reading of the ‘Flag Salute Song’ (Jhanda Salami Geet) or national song (Qaumi Tarana) of the revolutionaries. Actually, the idea of nationality, when we associate it with nationalism, has never been a simple and straightforward idea. Era-specific factors, contemporary circumstances, social structures etc. make the idea of nationality a complex, and at times contradictory idea. The idea of nationality, which was at the root of the Rebellion, should also be viewed from this perspective.

The ‘Flag Salute Song’ was written by Azimullah Khan Yusufzai, a key figure in the Rebellion, and was published in Delhi’s daily newspaper ‘Payam-e-Azadi’. The publisher of this Urdu-Hindi newspaper, started in February 1857, was Azimullah Khan and the editor-in-chief was Mirza Bedar Bakht, grandson of Bahadur Shah Zafar. (It is obvious that the newspaper had the patronage of Nana Sahib. Because his Diwan Azimullah Khan had brought a French printing machine to India in February 1857.) This newspaper also started publishing in Marathi from Jhansi in September 1857.

Notably, Badshah Zafar’s famous Pamphlet was published in ‘Payam-e-Azadi’. The circulation of this newspaper spread rapidly throughout North India. The newspaper declared its support for the rebellion on 29 May 1857. The British government immediately banned the newspaper’s publication on charges of treason. Bedar Bakht was hanged. Azimullah Khan is believed to have left for the Nepal border with Nana Sahib after the defeat at Kanpur, where he died of illness at the age of 28.

Azimullah Khan, a resident of Kanpur, was neither a soldier nor a feudal lord. He was from a very ordinary socio-economic background. His mechanic father had passed away in his childhood. He was fortunate enough to survive the famine of 1837-38 along with his mother. Later the mother also died. He received his education while living in an orphanage and working in an Englishman’s house. He first became secretary to several Britishers, and then held the post of Diwan of Nana Sahib. Nana Sahib promoted the polyglot (he knew English, French, Urdu, Persian and Sanskrit) and the intelligent Azimullah Khan to the post of Prime Minister. It is believed that Azimullah Khan, a charming personality, could not get Nana Sahib’s pension restored during his sojourn in England, but returned to India with the idea and strong determination to free India from British rule. He saw the myth that the British Empire was invincible being broken with his own eyes. He could see that the combined forces of England and France had been defeated by the Russian army in the Crimean War. Azimullah Khan seems to represent the concerns and efforts for the independence of the country made outside the realm of the consciousness of Navjagaran (renaissance).

The ‘Flag Salute Song’ is as follows:

We are its owners, India is ours,

A land more pious and charming than paradise, is our land.

We own it, India is ours,

The whole world is illuminated by its spirituality.

So wonderful, so new, so different from the rest of the world,

The stream of Ganga-Jamuna makes it fertile.

The snowclad mountain above guards us,

The sound of the ocean playing on the shore below.

Its mines are spewing out gold, diamond and mercury.

The world celebrated its grandeur.

The Firangi came from a distance and cast an evil eye,

Our beloved country was looted with both hands.

Today the martyrs have challenged you O people,

Break the chains of slavery and shower embers.

Hindu-Muslim-Sikh are our dear brothers,

This is the flag of freedom, we salute it.

If we interpret this song, we find that the British occupation has been identified as the national subjugation of India in the song. Because Indians are the natural owners of this country. It is true that the geographical extension of the Rebellion was mainly in North, East and Central India. But the claim of the revolutionaries is of India from the Himalayas to the sea. This is a fertile land, whose wealth is being looted by the British. The nuance of “Aisa Mantar Mara” suggests that the magic of Englishness (Angreziat) was dancing the heads of most of the Indians who were considered important. The echo of this nuance can be found in Gandhi’s ‘Hind Swarajya’, where he says that the British did not enslave us, we ourselves have accepted their slavery.

It is true that most of the princely states and battalions of the Indian British Army supported the British instead of supporting the rebels; Or remain neutral. The consciousness of renaissance promoted by the newly educated Bhadralok also does not connect with the Rebellion. In this song, the criterion of an authentic Indian of that time has been placed that the true Indian is the one who takes the initiative to break the chains of slavery on the call of the martyrs. It needs to be kept in mind that India’s independence, which became possible as a result of the struggle for independence after the Rebellion of 1857, was opposed by kings, princely states, communal organizations and many important individuals. The country also got divided due to misdeeds of such inauthentic Indians.

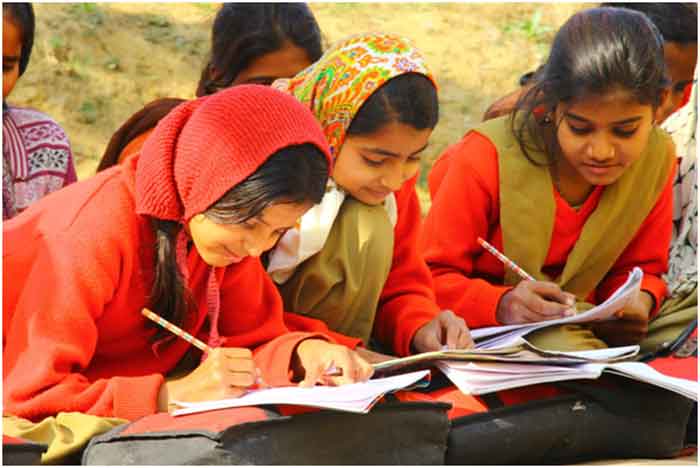

It is true that many times religious, casteist, ethnic, regional etc. fault lines emerge in the Rebellion. In a country the size of a subcontinent, with a deeply ancient society full of diversity as well as disparities, it was obvious for fault lines to emerge during the uprising. The song does not call for the country’s independence on the basis of religious identity. However, unity and love among all religious people has been highlighted. Perhaps, Azimullah Khan, while writing this song, wanted to convert the call for religious identity into a call for national identity. If the women of India had also been invoked in the song, the significance of the song would have doubled. Because, women, mainly living on the socio-economic margins played an important role in the Rebellion.

Needless to say, this song can be read in the context of the current neo-imperialist crisis and communal disharmony. The young generations of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh should at least do this important work.

Dr Prem Singh is associated with the socialist movement is a former teacher of Delhi University and a fellow of Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla