Although elaborate arrangements have been provided for eliminating iniquitous customs, practices and institutional arrangements, we need more than just laws to combat a problem as deep-rooted and multi-dimensional as casteism, which appears to have set in below the surface, and is corroding our moral fibre.

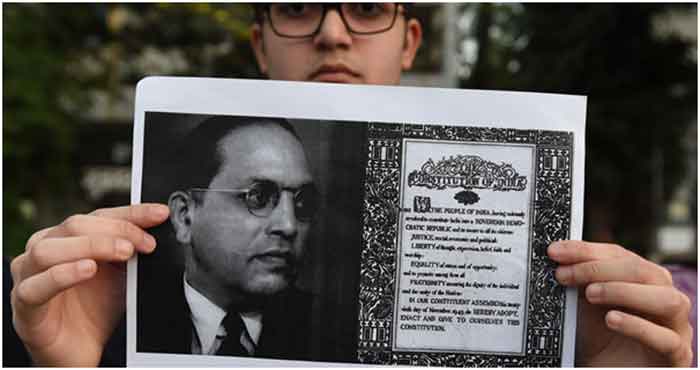

A student holding a placard with the Preamble of the Constitution at a protest against India’s new citizenship law outside the Gandhi Ashram in Ahmedabad. | Sam Panthaky/AFP

While drafting the Constitution of India, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar once said, “the only new thing, if there can be any, in a constitution framed so late in the day are the variations made to remove the failures and accommodate it to the needs of the country.” As truly conceived by Ambedkar, India’s Constitution turned out to be a unique document which in turn became an exemplar for many other countries. The main purpose behind the long search that went for almost three years was to strike the right balance so that institutions created by the Constitution would not be haphazard or tentative arrangements but would be able to accommodate the aspirations of the citizens of India for a long time to come. Democracy, as our political system, was adopted for the same.

With reference to democracy, Dr. Ambedkar expressed his concern in the Constituent Assembly. He said that, “we must make our political democracy a social democracy as well. Social democracy is a way of life which recognizes liberty, equality and fraternity, as the principles of life.” The concerns of Dr. Ambedkar become relevant to this day when one asks if it is really enough to just have democracy? What about various social and economic inequalities that continue to exist even today? Much remains to be done if they are to be reduced. In fact, the entire concept of social justice comes into picture then. Social Justice, to put in the words of J.S. Mill, implies, “something which it is not only right to do or wrong to do not do, but which some individual person can claim from us as his moral right.” It is in connection with this definition of social justice that the Constitution of India, with Dr. Ambedkar as its architect, has presented to the nation a document that enshrined fundamental values and highest aspirations shared by people. But the fundamental values are still denied to and aspirations crushed, purely on the basis of prevailing age-old practice of the caste system, which continues to be one of the most pervasive social identifiers in India. Accordingly, the Constitution of India guarantees equality before law (Article14), and enjoins the state to make special provisions for the advancement of Scheduled Castes (Article 15(4)). The Constitution of India categorically states that untouchability stands abolished and that its practice in any form is forbidden (Article 17). It also empowers the state to make provisions for reservations in appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens (Article 16(4)). Moreover, anti-discriminatory measures include the enactment of the Untouchability (Offences) Act, 1955 under which the practice of untouchability and discrimination in public places was treated as an offence. In 1976, the Act was reviewed in order to make it more stringent and effective and was designated as The Protection of Civil Rights (PCR), Act 1955. The Act provides for penalties for refusing access to Scheduled Castes to places of public use. Yet, despite all these constitutional provisions, the extent, magnitude and nature of crimes committed against Scheduled Castes mirror the oppressive and violent character of the caste system. The regular reportage of atrocities against Scheduled Castes is indicative of the fact that discrimination and humiliation are still being practiced, and that the traditional mechanisms of their enforcement are continue to be in vogue. Although elaborate arrangements have been provided for eliminating iniquitous customs, practices and institutional arrangements, including provisions in law, they act as deterrents only in a limited way. The official machinery and its laws are less respected by the civil society in certain spheres of civic life. Violence, overt or covert, inflicted on those belonging to Scheduled Castes, is rooted in the social structure and in societal relations which condemns the Scheduled Castes to a life of indignity and subordination. It is here that one is yet again reminded of Dr. Ambedkar, when he said, “caste is a state of mind.” Constitutional benefits are derived when society works for them. Caste is the real bane of India. To get rid of caste and its ill-effects, it is important to make India more inclusive. Thus, Dr. Ambedkar rightly said, “the aim of abolition of untouchability without trying to abolish the inequalities inherent in the caste system is a rather low aim.”

One of the most important tools capable of decreasing inequalities and shaping the destiny of mankind, is the institution of education. Education opens up new opportunities and enhances possibilities of making choices. Thus, the Constitutional provision of protective discrimination in the form of reservations in higher education and jobs have been provided to all groups which had been earlier deprived of it, since education has a significant role to play in enhancing equality and social mobility. Reservations make the compositions of elite positions more representative of the underlying social composition. This increases representation of the marginalized groups in such domains which are overly-represented by the so-called privileged castes. However, it cannot become a blanket solution for all times to come. What we need is to create opportunities for everyone. The whole idea of equality ought to be that the treatment we receive, and the opportunities we get, must not be pre-determined by birth. When that happens, caste is most likely to wither away. If this process is blocked, caste antagonism, discrimination and caste-based violence and atrocities will only flare up. Change is inevitable and essential, and can and should be facilitated harmoniously. We need more than just laws to combat a problem as deep-rooted and multi-dimensional as casteism, which appears to have set in below the surface, and is corroding our moral fibre.

Sargam Sanil, a Doctoral Scholar at the Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi. [email protected].