In India, the abduction scenes that lure historical figures from the present and make them part of established interests are gaining strength day by day. This process strips individuals of their history and ideals, reducing to mere glorified faces and appropriating them. Through assimilation of Ambedkar, the architect of a secular constitution and the most powerful emancipatory capital of Dalit communities, into the body politic of hyper-nationalism also mark the beginning of a new epistemic process. The photoshopped politics of Brahmanism, where individuals are abducted from history and subjected to cosmetic surgery to become the faces of their ideological representatives, is completing a circle, by taking on Ambedkar.

The Hindutva effort to present Ambedkar as a Hindu reformer gained strength through Golwalker. Asghar Ali Engineer observes that by the 1980s, Ambedkar and Phule had become symbols of anti-Muslim protests and Hindutva political agitation in Maharashtra. Situations like terrorism and Islamophobia, which emerged strongly in the 1990s, gave strength to the campaign. An attempt to cover up the history can be seen in these versions as well as in other Hindutva discourses. These versions forcefully open up the hitherto implicit argument that Ambedkar’s conversion was a return to the Hindu incarnation of the Buddha and to Hindu Dharma itself. Krishnakumar, a prominent leader of the RSS, introduces Ambedkar who declared, “I will never die a Hindu” and fulfilled it, as “a man who was proud to be a Hindu” (Organiser, 2015). Moreover, Organizer “finds” that Ambedkar was greatly impressed by the RSS, which was engaged in anti-caste struggle, and subsequently became an admirer of Hedgewar. It can be seen that what he aimed for through religious conversion was a well-equipped social modernization of the Dalit communities. A reading of his thoughts and writings from the 1930s onwards makes this point clear.

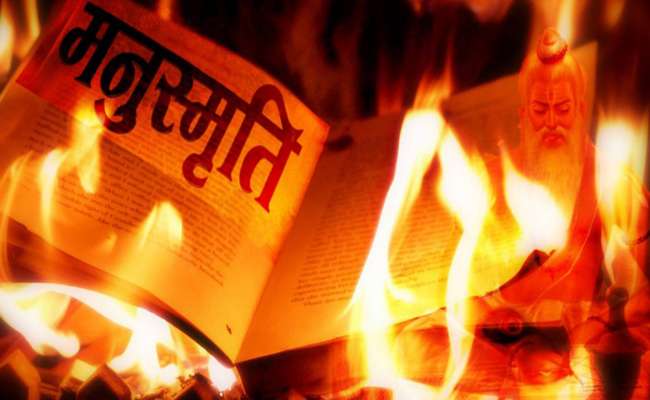

Ambedkar himself has made it clear that this speech was his declaration of struggle against hierarchical Hindu-scriptural premises and social attitudes. According to Sukumar Narayana, a prominent Ambedkar scholar, Ambedkar had been making slow and continuous efforts to convert the Dalit communities since the 1930s. Conversion can be seen to have made possible the recovery of Buddhism itself, which had been drawn into the Brahminic cultural world since the loss of political patronage and some revolutionary reminders to Dalit communities of their non-Hindu history. Another of the propaganda accompanying the abduction is that Ambedkar was anti-Muslim and anti-Christian, because of which he didn’t choose Christianity of Islam. Beyond this superficial argument, it can be seen that there were purely political and social reasons that led him to the choice of Buddhism. A strong indication can be gleaned from his writings that Ambedkar, believed that the social emancipation and material upliftment of DBA communities would not be easy to achieve with the visions of Islamic and Christian religions, where the limits of karmic science, general concepts of guilt-punishment-reward, fate-belief, heaven-hell govern all human activities.

He discusses in detail about a large Muslim community that could not give up its ancestral caste titles and traditional occupations and did not undergo any measurable material change even after conversion to Islam. Ambedkar’s writings make it clear that partition was a political trap for Muslim elites and that “Pakistan” would bring only defeat in every sense to the Indian Muslims, and believed that the kind of modernization and social reformation he envisioned will not be possible through conversion to Islam or chritianity. At the same time it can be seen that he did not oppose the conversion of individuals to Islam and Christianity. Ambedkar believes that the two basic states of Buddhism, love and wisdom, can be grasped quickly by the green minds of ordinary people. However, Hindutva is trying to make him anti-Muslim and anti-Christian by completely silencing such profound observations, studies and readings of history. It can be said that it was not the divinity of the Buddha but the sociability and practicality of the Buddhist ways that attracted Ambedkar to Buddhism. He thus constructed a new authorship to make Dalit communities part of modernity by reclaiming the Buddha from the existing social-political-knowledge premises.

Apart from using the emotional capital of Ambedkar as a political investment, it can be seen that Hindutva attitudes towards him and the Dalit community were always reactionary. Arun Shourie was the most forceful proponent of Hindutva’s position on Ambedkar, which was dismissive of anti-Dalit discourses emerging from post-colonial milieus. This is clear in Suri’s work “worshipping false gods” published in 1997. Ambedkar is described as a selfish, British agent and the seventh wage of modernity. The positions of Ambedkar, who reclaimed the Buddha from Brahmanical discourses, are incompatible. It is these realizations that put Ambedkar’s positions aside and Hinduism robs him of his face. This is done by sublimating Ambedkar’s symbol and socio-cultural capital into everyday political scenes. He clarifies that Hindutva parties have traditionally praised and criticized Ambedkar for failing to single out the Dalit community, which makes up a fifth of the population of North India. The latest example of this is the banning of the ‘Ambedkar-Periyar Students’ Circle’, at Madras IIT for ‘criticizing the Prime Minister’.

When Ambedkar is presented as anti-Muslim and Christian, we can read that independent DBA communities with Hindutva consciousness were becoming stronger, especially in places like Gujarat and Rajasthan. Anthropological studies of the communal riots in Rajasthan and Gujarat detail how these neo-communities are transformed into crucibles of supranationalism, and how subaltern and Dalit communities within Muslims become competing identities. Dalit leader Ramdas Athawale, Udit Raj and a section of the “Pulayar Mahasabha” in Kerala that supports the brahminic hindutva forces, beyond mere political ejaculates, it has to be said that it is a sign of the success of the Hindutva epistemology of making Ambedkar, other Dalit leaders, and Buddhism itself symbols and models of Hindutva.

Naveen Prasad Alex is a master’s student in biological sciences at the University of Turku, Finland. He is a Junior Fellow of the New York Academy of Sciences and has authored two books in Malayalam. He is also passionate about Anti-caste movements, Anthropology and politics.