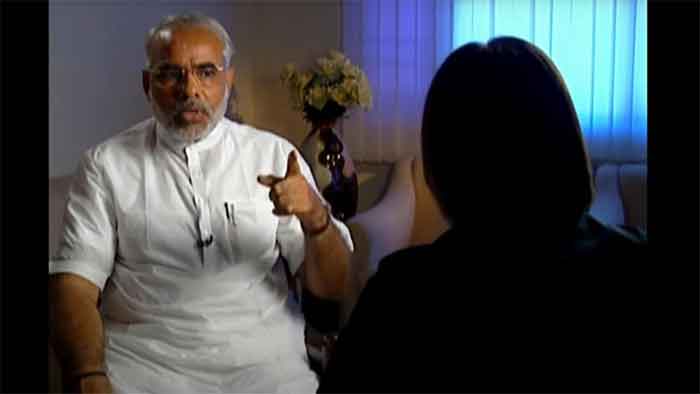

Past the halfway mark in the BBC documentary ‘India: The Modi Question’, Episode 1, is a clip of the BBC reporter interviewing Narendra Modi, then Chief Minister of Gujarat, soon after he had called for elections in a state still seething with the fresh wounds of post-Godhra communal riots in 2002. Every question she asks him, including about the violence she has seen with her own eyes, is met with the same hostile, menacing denial – “This is false propaganda”. Except, for the last question she poses: “When you look back over the last month — you’ve been the leader of this state through a difficult period — do you think there is anything you should have done differently? Without a second’s hesitation, Modi, for once, agrees. He says, “One area, where I was very very weak. And that was how to handle the media.”

Twenty years on, Modi the Prime Minister has taken good care to never repeat his ‘weakness’. Slowly but surely, much in the style of Germany under Hitler in the 1930s, the Modi government over two elected terms has nearly the entire Indian media in its pocket. So much so that when the government has ordered taking down of tweets and youtube postings on and of the documentary, the irony of the moment is almost lost.

For in every little act of censorship like this one, Modi and his friends come out looking like bigger fascists, only end up confirming what they refute – that they will brazenly extinguish the tiniest flickers of dissent or questioning in the way of their Hindu Rashtra project.

A few discerning voices ask – why impose such a blackout if you are not guilty, have formidable power, and supposedly no one to be afraid of?

The questions never go away so easily, do they?

Even for those of us who were not in any way related to the victims or knew their families, but were old enough in 2002 to follow the events at Gujarat, either reported widely in the media or through heart wrenching first-hand accounts from those who had visited the state, or the twists and turns in the court trials in the Ehsan Jafri and other major cases, or the murder of Haren Pandya and the developments following the Special Investigation Team’s report right up to the Supreme Court’s verdict and subsequent arrests of Sanjiv Bhatt, Teesta Setalvad and RB Sreekumar — the questions never, ever went away.

This documentary, by presenting original reportage at the time of the riots that many of us would not have seen, along with interviews of key people on both sides, responsibly and boldly resurrects those important questions on an inured public’s conscience. Importantly, it presents new and more detailed information to the public — about the British High Commissioner’s report to the UK government in 2002, which supposedly had found enough grounds to believe that Narendra Modi was ‘directly responsible’ for the Gujarat riots by directing the Gujarat police not to intervene when the Hindu backlash against Muslims had begun. It also quotes a European Union report “that reportedly found ministers in the government took active part in the violence and senior police officers were instructed not to intervene in the rioting.”

By doing this, the documentary has not only thrown open what was thought by many as a closed chapter in the present Prime Minister’s and his party’s track record. It has also called the bluff on all other major democracies of the world. For, it raises the question, would the UK, the EU, and other loud defenders of democracy and human rights take up the information presented in the documentary seriously and find possible ways to reopen trial in an international court of law for what was a crime against all humanity — or simply wait until the whole thing dies out again? Will these big and powerful people once again give more precedence to “maintain diplomatic ties with India”, as Jack Straw, the former British foreign secretary admits in the documentary, and as former Indian diplomat Satyabrata Pal’s article in The Wire brings out in the context of Modi’s 2003 visit to the UK when they had every chance to arrest him — or would they actually go beyond “being concerned” and do something to bring out the full truth behind the riots and actual justice to the victims if it is in their capacity — something they could perhaps have done in the first place with the findings of their inquiries of which we know only now to have existed?

Towards the end of the documentary, BJP leader Swapan Daspupta and right-wing sympathiser Swadesh Singh talk about putting a ‘full stop’ to the entire incident after the Supreme Court gave a clean chit to Modi. They talk about ‘closure’ and ‘moving on’.

Where is the closure for the families of the Dawoods, of Jafri, and hundreds of innocent people brutally killed who we don’t know by name? Where is the closure for the few brave officers who came forward staking their lives to speak truth to power, and for their families? Where is the closure for some of the best of our human rights defenders and intellectuals languishing in jails because they dared to care?

Finally, the documentary provokes us to think in new directions about probing this singularly important question that eludes all closure: where did the trail – “the chain of command” in the riots, as Dawood’s lawyer Imran and Professor Christophe Jaffrelot call it in the documentary, end – or begin?

The report of the British High Commissioner found that the Gujarat riots “had all the hallmarks of ethnic cleansing”. The killing, torture and rape of hundreds of innocent Muslim women, men, children were done by Hindu extremists preaching extreme violence, and whose existence and allegiance is beyond doubt. Many – including the authors of the report – also concur such organised, heinous acts could not have been committed without powerful, state backing. Now that with the Supreme Court ruling, it is unlikely for this allegation to be re-examined within India, what are the possibilities, in the light of all that this documentary reveals, and the unique circumstances India finds itself in today, that it is freshly examined at international forums for justice? We hope in the coming days, we will hear from the best of human rights and legal experts on this.

For try as they might, Modi and his team have not heard the last word on Gujarat 2002, neither within India, nor internationally. The BBC documentary gives us renewed strength in the belief that humanity cannot go silent, all at once.

(Sowmya is an independent writer)