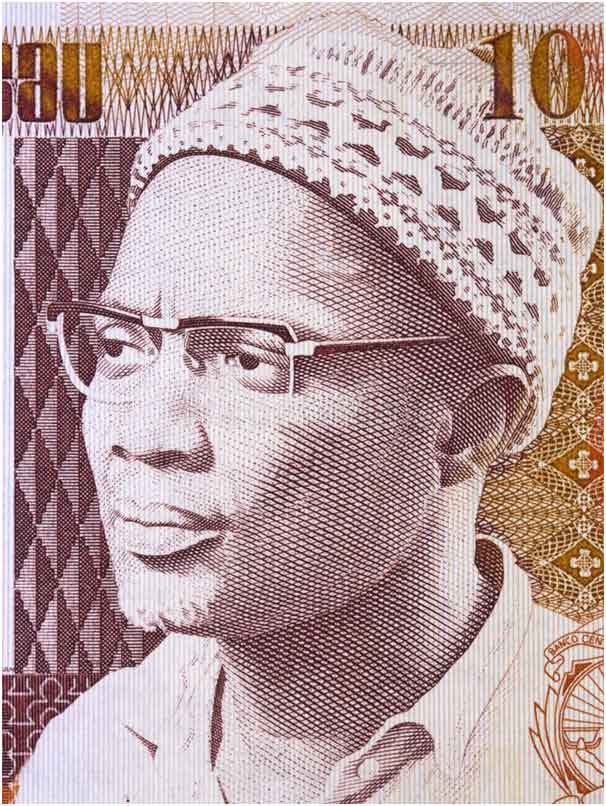

Amílcar Lopes da Costa Cabral was born September 12, 1924 in Bafatá, Guinea-Bissau, one of Portugal’s African colonies. On January 20, 1973–50 years ago Cabral was murdered by fascist Portuguese assassins just months before the national liberation movement in which he played a central role won the independence of Guinea-Bissau.

Cabral was amongst the most dialectical, critical and creative Marxist thinkers of the last century who made a profound influence on liberation struggle. and its link with thought process.

This particular struggle was waged for the liberation of not just one country–Guinea-Bissau, where the fighting took place–but also for another geographically-separate region, the archipelago Cape Verde. Cabral and the other leaders of the movement understood that they were part of a larger anti-colonial struggle and global class war and, as such that their immediate enemies were not only the colonial governments of particular countries, but Portuguese colonialism in general. For 500 years, Portuguese colonialism was constructed upon the slave trade and the merciless subjugation of its African colonies: Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, Sao Tome e Principe, Angola, and Cape Verde.

Despite the gigantic strength of their enemies, the struggle led by the relatively small population in Guinea-Bissau prevailed, remaining a beacon of inspiration to this day.

As a result of his role as a national liberation movement leader for roughly 15 years, Cabral had become a widely influential theorist of decolonization and non-deterministic, creatively applied re-Africanization. Although not fully acknowledged in the field of education Cabral’s decolonial theory and practice also sharpened and influenced the trajectory of Freire’s (1921-1997) thought. Through the revolutionary process led by Cabral, Guinea-Bissau became a world-leader in decolonial forms of education, which moved Freire deeply.

That is, because of the nefarious process of Portuguese colonialism, which included centuries of de-Africanization, re-Africanization, through decolonial forms of education, was a central feature of the anti-colonial struggle for self-determination.

Cabral’s dialectical unity, building the Party, and the “Weapon of Theory”

Cabral integrated with the world dialectically. As a theory of change, dialectics has been at the center of revolutionary thought since Marx and Engels. Cabral manoeuvred it it with great craft. Dialectically grasping how contending social forces driving historical development are often buried, Cabral excelled at unravelling them, and in the process, successfully mobilized the masses serving as the lever of change.

Cabral knew that the people must not only abstractly understand the co –relation of forces behind the development of society, but they must establish an anti-colonial practice that concretely, collectively, and creatively enable them see themselves as one of those forces. To do so, however, the masses had to be organized into and represented by a Party.

In 1956, Cabral helped found the African Party for Independence (PAI), which later became The African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC). The PAIGC was the first ever communist party in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, and its founding was a monumental and inspiring feat.

In The Weapon of Theory, a 1966 address in Havana, Cabral summarised the link between national liberation and socialism, telling the attendees that “in our present historical situation extinguishing of imperialism which uses every means to establish its domination over our peoples, and consolidation of socialism throughout a large part of the world — there are only two possible paths for an independent nation: to return to imperialist domination (neo-colonialism, capitalism, state capitalism), or to take the way of socialism.”

Of course, revolutionary crises do not emerge from the correctness of ideas alone, but are moulded by deteriorating economic conditions and a crisis in the legitimacy of the state and its ability to meet the peoples’ needs. In the 1940s there were several droughts that left tens of thousands of Cape Verdeans dead. Portugal’s barbarism and indifferent response, situated in the context of the escalating poverty and suffering within its African colonies, began to alienate even the most privileged strata of the colonial state.

What made Cabral one of history’s great communist leaders was his theoretically-grounded tactical flexibility, which was essential for a continuous flux in balance of forces. In-the-midst-of-struggle decision-making, in other words, is enhanced by theory and organization, which enables the ability to quickly grasp the immediate and long-term consequences of the flux of balance of power.

For example, in 1957 in Paris, Cabral and two Angolans formed the Movimento Anti-Colonista of Africans from the Portuguese colonies during the Algerian War. The three, in Angola, would go on to form the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola. What developed was one of the toughest anti-colonial fights in Africa.

To explain struggle, Cabral compared it to the tension between centrifugal force and gravity. As a concrete example Cabral notes that for a spaceship to leave the Earth it must overcome the force of gravity. Cabral then characterizes Portuguese colonialism as an external force imposed upon the people and only through the combined force of the people united can the force of colonialism be overpowered.

In the address, Cabral theorized the dialectical nature of movement and change focusing specifically on how the anti-imperialist struggle must emerge from the concrete conditions of each national liberation movement.

Cabral knew that to defeat Portuguese colonialism in Guinea-Bissau, the liberation struggle could not merely reproduce the tactics of struggles from other contexts, like Cuba. Rather, every particular struggle has to base its tactics on an analysis of the specifics of its own context. For example, while acknowledging the value of the general principles Guevara outlined in his Guerilla Warfare, Cabral (1968b) commented that “nobody commits the error, in general, of blindly applying the experience of others to his own country. To determine the tactics for the struggle in our country, we had to take into account the geographical, historical, economic, and social conditions of our own country, both in Guinea and in Cabo [Cape] Verde.”

Responding to Guevara’s argument, based on the experience of Cuba that revolutionary struggles go through three predetermined phases or stages Cabral stated:

Cabral’s assessment was also reflected dialectical insight that the conditions in any one country do not develop in a isolate form by external forces. Not only were deteriorating conditions in Portugal, the imperial mother country, shifting the balance of forces in favor of national liberation movements in its African colonies, but the emergence of these struggles coincided with the successful revolution in China in 1949.

Conscious of this larger dialectical totality, which illustrates the link between seemingly separate, unrelated parts, Cabral consciously, integrated solidarity with Portugal’s working-class. Representing the colonized Indigenous peoples of Guinea-Bissau Cabral successfully reached out to the oppressed of Portugal in solidarity against their common class enemy, the fascistic Portuguese capitalist/colonialist class.

With dialectical theory and the spirit of anti-colonialist and anti-capitalist unity the revolutionary forces in Guinea-Bissau routinely freed Portuguese prisoners of war. Cabral (1968c) used such occasions to make public statements designed to educate and win over Portugal’s persecuted working-class to shift the balance of power away from Portugal’s fascist state.

The liberation of the Portuguese was connected to the liberation of Portugal’s African colonies.

Rather than a theoretical position worked out abstractly in isolation, it was formulated practically. It had serious and determinant results. Portuguese officers refused orders to fight in Africa, and some formed an Armed Forces Movement that supported the demands for independence.

The Portuguese soldiers led a rebellion against fascism at home, which ended more than 40 years of fascist rule. It planted the seeds for a popular upsurge that nearly claimed power for the Portuguese workers. These social convulsions in the imperial center in turn facilitated the independence of Portugal’s African colonies.

De-Africanization and anti-colonial resistance

The small region in West Africa that the Portuguese would claim as Guinea-Bissau contained more than a dozen distinct ethnic groups. Slavers worked overtime to create divisions between them. These divisions enabled slavers to enlist one group to facilitate in the enslavement of others. This anti-African divisiveness would lay the foundation for centuries of de-Africanization.

The devastation of such practices reflects reports that European colonists with smaller African colonial holdings like Portugal were amongst the most desperate and thus cruellest in their efforts at maintaining their occupations. Consequently, Indigenous resistance to Portuguese colonialism was so widespread for so many centuries that colonial rule was always limited to specific regions. In other words, colonial forces were never completely able to establish stranglehold of state power of indigeneity.

It is therefore not surprising that the Portuguese were not able to depend solely on state violence for social control, but required intensive ideological manipulation as well. The attempt to extinguish Indigenous languages and cultures was crucial. Toward these ends, the colonial authorities propagated a hypocritical discourse that claimed their colonies were integral to the metropolis or mainland while simultaneously brutally exploiting them.

Fascist Portugal and the struggle

The brutality in which the Portuguese ruling-class managed its African colonies would eventually be directed at its own working-class with a fascist turn in 1926. Rodney (1972/2018) explains that “when the fascist dictatorship was inaugurated in Portugal in 1926, it drew inspiration from Portugal’s colonial past” (244).

The decline of Portuguese capitalism that gave way to Portuguese fascism would only deteriorate with the global capitalist crisis of the 1930s. Consequently, the desperation of Portugal’s capitalist class intensified. For example, when Salazar became the dictator of Portugal in 1932, he declared that the “new” Portuguese state would be built off of the exploitation of “inferior peoples”

Whereas the French ruling class had moved to neocolonialism by 1960, Portugal’s decline had rendered it still largely backward and feudalistic. Out of desperation, Portugal became even more dependent on ruthlessly exploiting peoples not just in its colonial holdings, but within its own national territory.

Fascist Portuguese leaders, therefore, employing increasingly violent forms of social control, rejected African demands for self-determination. In response to the growing wave of national liberation movements in their African colonies, the Portuguese establishment sent armed forces to repress the struggle. Rather than cower in the face of Portuguese fascism and overall deteriorating conditions, national liberation movements grew and spread.

Anti-colonialism and decoloniality

Based on his comprehensive understanding of the distinctiveness of the agricultural situation in his country, Cabral knew that the primary economic issue the majority peasant population faced was not access to land, as was the case in other colonies. Rather, the issue was unsustainable trade deals that were particularly destructive given the colonial insistence on not farming for sustenance but for export through single-crop production.

The demand for cultural and political rights in the face of fascistic Portuguese colonialism was another demand that resonated widely.

Cabral focused on the political developments required for building a united movement for national liberation. In his formulations, he argued that the armed struggle was intimately interconnected with the political struggle, which were both part of a larger cultural struggle.

Cabral’s Marxist formulations on culture were vital for the larger struggle and for resisting colonial education. He acknowledged that fascists and imperialists were well aware “of the value of culture as a factor of resistance to foreign domination,” which provided a framework for understanding that subjugation can only be maintained “by the permanent and organized repression of the cultural life of the people” A central part of developing this revolutionary consciousness was the process of re-Africanization. This was not meant to turn the clock back to the past, but a way to reclaim self-determination and build a new future in the country.

At the same time, Cabral opposed harbouring ill will toward those who had studied or who desired to study abroad. Rather, Cabral encouraged pedagogy of patience and understanding as the correct approach to winning people over and strengthening the movement.

Victory before Victory

Even though Cabral was murdered before victory, the ultimate fate of Portuguese colonialism had already been settled years before his death, and he knew it. For example, in a communique released on January 8, 1973, a mere 12 days before he was assassinated, Cabral (1979) concludes that the situation in Guinea-Bissau “since 1968… is comparable to that of an independent state” (277). Cabral reports that after dozens of international observers had visited Guinea-Bissau, including a United Nations Special Mission, the international legitimacy of their PAIGC-led struggle was mounting. It had become irrefutable that:

Yes, Cabral was killed before the final expulsion of Portuguese colonialism, but, in a very real sense, he still ushered in a new, independent state.

Freire and Cabral’s decolonial education in a liberated Guinea-Bissau

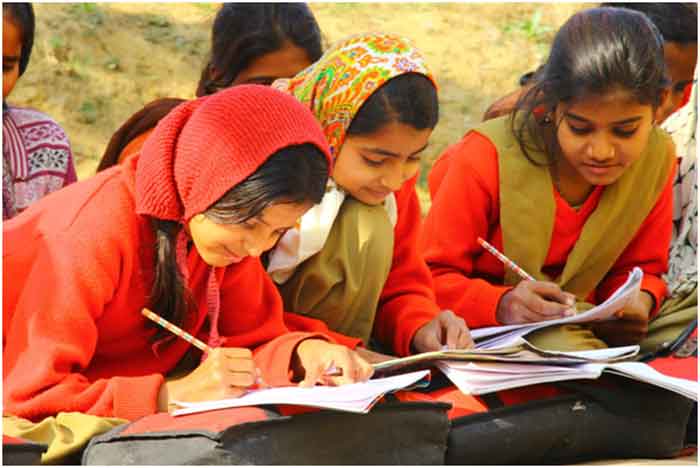

The importance of education was elevated to new heights by Cabral and PAIGC leadership at every opportunity. It therefore made sense for the Commission on Education of the recently liberated Guinea-Bissau to invite the world’s leading expert on decolonial approaches to education, Paulo Freire, to participate in further developing their system of education.

The colonial model of education was constructed to instill sense of inferiority in the youth. Colonial education seeks to establish command over learners by treating them as if they were passive objects. Integral part of this process was undermining the history, culture, and languages of the people. In the most cruel way then colonial schooling sent the message that the history of the colonized really only began “with the civilizing presence of the colonizers”

For Freire, Cabral was certainly an advanced revolutionary educator. Rejecting predetermination and dogmatism, Freire’s team did not construct lesson plans or programs before coming to Guinea-Bissau to be imposed upon the people.

Upon arrival Freire and his colleagues continued to listen and discuss learning from the people. Only by learning about the revolutionary government’s educational work could they assess it and make recommendations. Decolonial guidance, that is, cannot be offered outside of the concrete reality of the people and their struggle. Such knowledge cannot be known or constructed without the active participation of the learners as a collective.

Freire (1978) was aware that the education that was being created could not be done “mechanically,” but must be informed by “the plan for the society to be created” (14). Although Cabral had been assassinated, his writings and leadership provided a platform in the creation of a force with the political clarity needed to battle the resistance emerging from those who still carried the old ideology.

Through their process revolutionary leaders would encounter teachers “captured” by the old ideology who consciously worked to undermine the new decolonial practice. Others, however, also conscious that they are brainwashed by the old ideology, nevertheless strive to extricate themselves of it. Cabral’s work on the need for the middle-class, including teachers, to commit class suicide, was instructive. The middle-class had two choices: betray the revolution or commit class suicide. This choice remains true today, even in the US.

The work for a reconstituted system of education had already begun during the war in liberated zones. The post-independence challenge was to improve upon all that the progress that had been achieved in areas that had been liberated before the wars end. In these liberated areas, Freire (1978) concluded, workers, organized through the Party, “had taken the matter of education into their own hands” and created, “a work school, closely linked to production and dedicated to the political education of the learners”

After the war the revolutionary government chose not to simply close down the remaining colonial schools while a new system was being created. Rather, they “introduced…some fundamental reforms capable of accelerating…radical transformation” (20). For example, the curriculum that was saturated in colonialist ideology was replaced. Students would therefore no longer learn history from the standpoint of the colonizers. The history of the liberation struggle as told by the formerly colonized was a fundamental addition.

However, a revolutionary education is not complete with simply replacing the content to be passively consumed. Rather, learners must have an opportunity to critically perceive own thought process in relation to the new ideas. For Freire, this is the path through which the passive objects of colonial indoctrination begin to become active subjects of decoloniality.

Assessment here could not have been more grounded. What was potentially at stake was the success of the revolution and the lives of millions. This is a lesson relevant to all revolutionaries who must continually assess their work, always striving for improvement. In this way it was clear to Freire that they must not express “uncontained euphoria in the face of good work nor negativity regarding…mistakes”

What Freire and his team concluded was that “the learners and workers were engaged in an effort that was preponderantly creative” (28) despite the many challenges and limited material resources. At the same time, they characterized “the most obvious errors” they observed as the result of “the impatience of some of the workers that led them to create the words instead of challenging the learners to do so for themselves”

From the foundation Cabral played such a central role in building, and through this process of assessment, what was good in the schools was made better, and what was in error was corrected. As a pedagogue of the revolution Cabral “learned” with the people and “taught them in the revolutionary praxis” (33).

Conclusion

Freire’s work and practice have inspired what turned into a worldwide critical pedagogy movement. The emphasis to decoloniality occupies one of critical education’s most formidable advances, which demands a more thorough return to Cabral.

As the socialist and anti-racist movement in the US continues to intensify politically, political sophistication, the educational lessons from the era of anti-colonial socialist struggles will so grow in relevance.

I recommend ‘Unity and Struggle’ by Cabral for everyone, with all his speeches and writings..

Harsh Thakor is freelance journalist who has studied national liberation movements