An important feature of life in Kenya, as in other capitalist countries, is the ever-present exploitation of labour and resources in every aspect of life. It is so prevalent that it is often taken for granted as a basic condition of life on earth. Yet exploitation is not part of social life as such. It is, however, part of life under capitalism. The Njaa resistance, the police brutality, lack of food, water, jobs, medical care, education all result from exploitation of labour that deprives people of the wealth they create. This wealth is the surplus that is appropriated by capitalists, mostly foreign, but also local compradors too.

How did we get to this situation is a question that needs answers if we are to restore people’s wealth to people. The first point to note that Kenya is not unique to find itself in this exploitative situation. It has happened in all capitalist countries. A few quotes explains the ideology behind this situation. Magdoff and Foster (2023) say:

Capitalism has always been based on the expropriation of land, resources, and human lives in order to create the conditions for the exploitation of labor. The Industrial Revolution, as Karl Marx indicated in the nineteenth century, was made possible by means of the brutal enclosure of the commons in England together with the even more barbaric colonization abroad carried out by the European powers, encompassing “the discovery of gold and silver in the Americas, the extirpation, enslavement, and entombment in mines of the indigenous population of those continents, the beginnings of the conquest and plunder of India, and the conversion of Africa into a preserve for the commercial hunting of blackskins.” Taken together, these forms of “original expropriation” formed the historical basis for the “genesis of the industrial capitalist.”

Marx Memorial Library shows the background of finance capitalism:

… before you can invest, you must steal and before you can employ, you must enslave… “Primitive accumulation” means the acquisition of capital (physical or financial) by expropriation rather than through exploitation.

Exploitation — paying workers less than the value they create (the difference, surplus value, is accumulated as profit) — is the characteristic and universal feature of “mature” capitalism.

Expropriation means seizure, confiscation, robbery; it is direct.

Kenya has seen both these aspects of capitalism — expropriation of peasant land and exploitation of labour. Expropriation of land started with the early stage of colonialism. Land was then ‘stolen twice’ at independence when the comprador government refused to return the stolen land to peasants and instead appropriated it for its own use and for foreign corporations.

Exploitation of labour followed the expropriation of land from peasants who were then forced to sell their labour as they had no other means of survival.

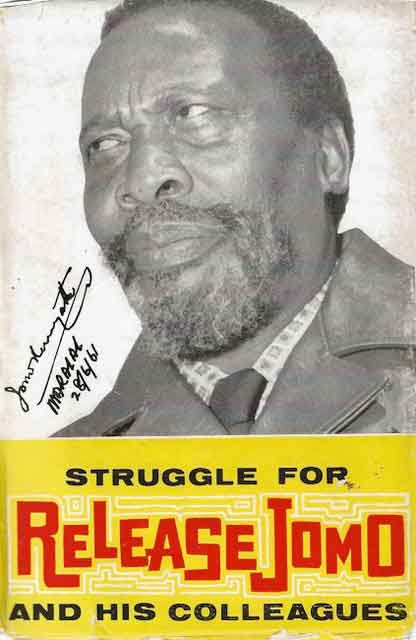

The above two processes were the basis of class formation, with workers and peasants on the one side and the bourgeoisie on the other. This provided the condition for the formation of trade unions. Workers in factories, public service, domestic and other forms of employment came together to form trade unions. These unions united under the umbrella of the East African Trade Union Congress.

This was then, what about after independence? There was a shift of power from the colonial capitalists to the comprador ruling class, with profits from land and labour mostly expropriated by multinational corporations, plantations and companies from USA, UK and other capitalist countries. The comprador ruling class controlled state power which included anti-working people laws and armed forces used mainly to suppress working class resistance.

This economic power of the state was consolidated by international financial institutions, the IMF and the World Bank. The capitalist noose around the people was now complete. Ha-Joon (2012) explains the causes of the ‘IMF riots’:

Throughout the 1980s and 90s, when many developing countries were in crisis and borrowing money from the International Monetary Fund, waves of protests in those countries became known as the “IMF riots”. They were so called because they were sparked by the fund’s structural adjustment programmes, which imposed austerity, privatisation and deregulation.

The IMF complained that calling these riots thus was unfair, as it had not caused the crises and was only prescribing a medicine, but this was largely self-serving. Many of the crises had actually been caused by the asset bubbles built up following IMF-recommended financial deregulation. Moreover, those rioters were not just expressing general discontent but reacting against the austerity measures that directly threatened their livelihoods, such as cuts in subsidies to basic commodities such as food and water, and cuts in already meagre welfare payments.

The IMF programme, in other words, met such resistance because its designers had forgotten that behind the numbers they were crunching were real people. These criticisms, as well as the ineffectiveness of its economic programme, became so damaging that the IMF has made a lot of changes in the past decade or so. It has become more cautious in pushing for financial deregulation and austerity programmes, renamed its structural adjustment programmes as poverty reduction programmes, and has even (marginally) increased the voting shares of the developing countries in its decision-making.

The fact remains that after almost 60 years of independence, Kenya and its working class have been pushed into the capitalist prison run by the dictated from IMF, World Bank and WTO. The struggle to get out of this prison will be hard and long, perhaps violent too, as capitalism does not give up easily.

Shiraz Durrani is a Kenyan political exile living in London. He has worked at the University of Nairobi as well as various public libraries in Britain where he also lectured at the London Metropolitan University. Shiraz has written many articles and addressed conferences on aspects of Kenyan history and on politics of information in the context of colonialism and imperialism. His books include Kenya’s War of Independence: Mau Mau and its Legacy of Resistance to Colonialism and Imperialism, 1948-1990 (2018, Vita Books). He has also edited Makhan Singh – A Revolutionary Kenyan Trade Unionist (2017, Vita Books) and Pio Gama Pinto: Kenya’s Unsung Martyr,1927 – 1965 (2018, Vita Books). He is a co-editor of The Kenya Socialist. and edited Essays on Pan-Africanism (2022, Vita Books, Nairobi). His latest book (2023) is Two Paths Ahead: The Ideological Struggle between Capitalism and Socialism in Kenya, 1960-1990. Some of his articles are available at https://durranishiraz.academia.edu/research and books at: https://www.africanbookscollective.com/search-results?form.keywords=Shiraz+Durrani