This year, on April 10th, we commemorated the 30th martyrdom anniversary of the assassination of Chris Hani. His life story and death was as intriguing as the greatest of revolutionaries, making a profound impact on South Africa’s political history. Without doubt one of the most dedicated impactful and creative political activists of South Africa, who shook apartheid. He was assassinated when a new epoch was being crystallised in early 1990s, with society evolving toward democratic political rule.

Life Journey

Chris Hani’s life political journey started in the mid-20th century with Hani as a student activist, a member of the African National Congress, Umkhonto region, where he subsequently became commander, and a member of the South African Communist Party’s (SACP) underground structures.

With the banning of the ANC, the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) and other organisations of the liberation movement in 1960, following the Sharpeville Massacre, the movement received a mortal blow by the mid-1960s.

At this point, Soviet Union intervened, and provided extensive military training to hundreds of MK cadres, including Hani Tanzania and Zambia, which gained their independence from Britain in 1961 and 1964 respectively, allowed the ANC and MK to set up bases in their newly liberated territories, and Hani was involved in building the first military camps of South African liberation fighters.

In 1967, Hani led an operation to insert ANC and ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People’s Union) troops into Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), with an objective of opening up penetration into South Africa. Militarily the campaign led to the loss of more than half the cadres and a forced retreat into Botswana – and yet it elevated the morale of black South Africans in a grave period for the liberation struggle. By the mid-1970s, Hani was at the head of an MK base in Lesotho, the purpose of which was to reinforce small groups of cadres back into South Africa for short periods in order to organise armed sabotage cells. Hani was one of the first to be reinstated, in 1974, successfully evading the South African intelligence services and setting up several cells in Johannesburg, before making his way back over the border four months later.

The operations escalated in a serious way after 1976, as thousands of young militant South Africans were forced out of the country, or chose to leave, in the aftermath of the Soweto Uprising. These young people were ready to fight, and with boundless enthusiasm joined the MK’s camps in Tanzania and Zambia. Chris, who by this time had been placed on the ANC’s Revolutionary Council (and was Assistant General Secretary of the SACP), spearheaded military training and political education for these new recruits. Few better understood the pulse or idioms of the masses or could so lucidly explain politics to them.

Through this revolutionary uprising in South Africa, the liberation forces began to break the backbone of apartheid. Hani’s brilliant leadership was rewarded and he was appointed MK’s political commissar in 1982 and its chief of staff four years later.

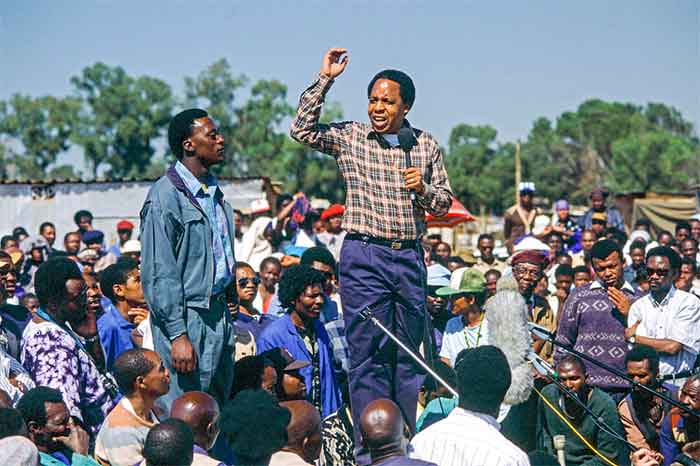

In April 1990, Hani returned to South Africa on a provisional amnesty order from the white government, as it advanced towards a negotiated settlement. He immediately embarked on travelling the country to educate people about the political process taking place and also to elevate their socialist consciousness.. He fully grasped that the revolutionary forces were not powerful enough to defeat the South African state outright, an only through integration of armed and mass struggle, a negotiated solution could be arrived at would advance freedom struggle to a higher plane.

In December 1991, Hani was elected to the post of general secretary of the SACP, and gave up his post as MK chief of staff in order to focus on grassroots development of the party. He was fairly clear that the apartheid era was reaching it’s doom, and Chris saw the necessity to strengthen the position of the left within the Congress alliance, in order to promote interests of the workers and peasants in the post-apartheid era.

Chris Hani was murdered on 10 April 1993 in Johannesburg by a fascist gunman by the name of Janusz Waluś, who was working with a senior South African Conservative Party MP on a plot to assassinate a number of liberation fighters and thus spark a civil war along race lines, sabotaging the negotiations to end apartheid. Their plot was unsuccessful, as the massive wave of turbulence at Hani’s death was garnered towards a new plane in the peace process. South Africa’s first democratic election – one of the most historic events of the twentieth century – took place a year later, on 27 April 1994.

Approach towards Socialism

Hugh Macmillan, the author of the 2014 biography Chris Hani and other books on the liberation struggle, narrated how Hani cultivated his socialist ideas further through international experiences, such as training programs, exchanges with communist parties from other countries, and by attending international conferences. Hani had the fortune of witnessing the ebb and flow of 20th-century socialist governments, and could draw lessons from these countries while linking them to the South African scenario..

Similar to leader Joe Slovo, Hani argued that socialism had been distorted and it was imperative to restructure it to reclaim it from these perversions. They rejected the sectarian vanguardist, or statist autocratic models that characterized most 20th-century socialist societies, as well as the revisionist nature of the Soviet Union that violated basic socialist political values. However, in no uncertain terms, he challenged the ‘end of Communism’ thesis propounded by capitalist economy advocates.

While he was always ready to bridge the link between nationalism and Marxism, he understood that both were an integral part of an existent historical reality. To Hani, Marxism had to be applied to concrete revolutionary conditions and practice. He gave this idea a concrete form by formulating and constructing practical programs that mobilised the working people and the oppressed. Hani launched and led the SACP’s “Triple H” (Health, Housing and Hunger) campaign in the early 1990s because of the interrelated nature of these challenges. Its very relevance in the present situation, has made the party revive it today and embark on the “Hunger Eradication, Health, Human Settlements, and Water” (Triple H and W) campaign as part of Annual Red October Campaign. The theory of Marxist ecology illustrates the link between the National Democratic Revolution, socialism, and the Triple H and W, which are all manifested in the life of Hani.

In Hani’s view, socialism is not about big concepts and heavy theory, but providing decent shelter for those who are homeless or water for those who have no safe drinking water, and a life of dignity for the old.

A Hani made memorandum led to the epoch-making 1969 ANC Morogoro Conference, which adopted four key pillars of the struggle: namely, mass mobilization, international solidarity, and underground and armed struggle. The conference also established the Revolutionary Council under the leadership of the then ANC President Oliver Tambo. The memorandum also pointed that there were certain trends which were very alarming and discouraging g to genuine revolutionaries. These comprise the opening of unknown business enterprises which have never been probed by the leadership of the organization.

Hani’s main shortcomings were that he failed to understand the relevance of the Sino-Soviet split, the revisionist nature of USSR, or the relevance of the Chinese Cultural Revolution and Chinese path to liberation struggles. Hani was unable to sharpen the inclination of armed struggle or anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist movements, to check the compromise of the ANC.

Main Lessons

There are four main lessons that can be imbibed from Hani’s contribution. First, the question of violation of human rights. The country was ranked highly in several international comparative indexes on democracy and civil liberties, such as Freedom House and the Ibrahim Index of African Governance. However, high levels of socio-economic exclusion, poverty, inequality, and uneven spatial development characterize post-1994 South Africa

Hani emphasized democratizing the economy through establishing different social ownership patterns, extending social redistribution, protecting labour rights and other forms of redress were as salient as protecting political civil liberties. Several experiences from across the globe and internal SACP influenced Hani’s outlook. This included social democratic models implemented in countries such as Sweden.

Hani is mainly portrayed as a revolutionary MK commander who basically concentrated on traditional military concerns. The historical archives contradicts verify that Hani always gave priority to political education and theory as stating that military action must always be backed by rigorous political education, and left no stone unturned in combating any attempts to reduce political strategic questions to narrow militaristic goals. Hani stressed that to become more Africanised or Afrikanised that the CPSA must a, study the conditions in South Africa and sum up the demands of the toiling masses from first-hand information.

Chris Hani’s response in a 1993 interview with Luli Callinicos illustrates this point. He spoke about the “need to yoke together the national and the class struggle,” while recognizing that the priority is “national liberation, the liberation of mostly the blacks, leading to a democratic situation.”

The third contribution from Chris Hani’s life history and political legacy was his adherence to constructing mass-based, working-class struggles, led by alliances of unions, civil society organizations, religious groups, youth formations, and political parties. The clandestine work he undertook with several politically oriented civil society formations in the 1970s and 1980s planted the seeds for it. He was highly influenced by in other liberation struggles, especially in countries such as Vietnam, which emphasized popular legitimacy and support. This distinguished from the orthodox socialist vanguardism that granted absolute authority to the communist parties.

This escalated the SACP membership in the early 1990s. Hani’s emphasis on building a broad left front is imperative for contemporary political debates. South Africa’s society is experiencing a polycrisis, which, is attributed to two main systemic structural failures: a market-led neoliberal democracy and delegitimized state institutions. Such economic and social policy shortcomings reverse efforts aimed at democratizing the country’s economy to address past and present socio-economic injustices.

Hani, in the late 1970s and early 1980s propelled creation of trade unions, emerging black trade unions, black consciousness movements, and black civic organizations.

In 1983, Hani spoke about understanding and thorough knowledge of all the classes and strata ranged against the enemy which arises as a result of collection of data, of the nation’s political connections and interactions with numerous patriotic organizations, and trade unions. He expressed how imperative it was to pay undue respect to all aspects of mass mobilisation, to crystallise objective conditions.

Comrade Chris Hani fourth contribution was one of acting as one of the leading exponents in debates about regenerating left politics and leadership in order to fortify the liberation movement. He even extended this contribution to leadership questions in the post-transition era. Historically, it has it’s roots in the fierce challenge for internal democracy and organizational renewal he led in the ANC and SACP during the 20th century. The content of the Hani Memorandum (1969/1970) and the lack of strategic reflections on the Wankie Campaigns illuminate this point. The demands in both cases addressed the very crux of renewing left politics: a critical analysis of class fissures in the movement; corruption; abuse of political office; membership control; responsive leadership; and linking political strategy with working class needs.

Hani’s capacity for self-introspection and criticism was reflected throughout his reflections on the new government during interviews. He repeatedly warned against the ANC-led alliance government turning eclectic and repeating past errors of other liberation movements. Hani was bold in re assessing left ideology or political praxis so it still remains socially and politically relevant.

Relevance Today

The leadership crisis fermenting in South Africa, the current state of alliance and the factional battles that have stained the liberation movement are insults to the memory of Comrade Hani. South Africa is facing an untold energy crisis and many other challenges, which the neoliberal capitalist path has ignited. Hani always guarded against foreign tendencies spurred by factionalists and other counterrevolutionaries in our movement. To the last tooth he would have rebuked those who are using the movement to promote their own personal interest, as well as support their honesty in attempting to update and resurrect the ANC and South Africa.

Hani would have waged a bitter battle against those who are in power in South Africa today, for failing to address the major factors affecting the vulnerability of the working class and poor to COVID-19 and other health hazards. Hani would have raised his fists against the wealthier capitalist countries, such as the United States, which extract super profits from people of the third world.

The policy directives today place priority on market-controlled development models, which escalate labour market flexibility, diluting financial exchange controls, privatizing public goods, and minimise welfare support as principal measures for sustained economic development. These policy choices, dictated by dominant international financial institutions, continue to torment South Africans. An alternative human rights-based economic and social policy structure is required. Left-leaning political organizations in the country have not addressed this polycrisis adequately.

In the last 30 years penetration of globalisation has permeated growth of capitalism considerably in South Africa to nullify all democratic organised resistance and soft pedal with racist or neo-nazi forces. Leaders like Chris Hani need to be re born to revive the radical movements.

The South African courts in November, last year ordered the release of Hani’s murderer Janusz Waluś, who has spent nearly three decades in jail for the 1993 killing, before he was ironically stabbed by a jail inmate. This testifies the reactionary nature of the state, even in post-apartheid era.

Harsh Thakor is freelance journalist who has done extensive research on national liberation movements. Indebted to information from Khwezl Mabasa in ‘Africa is a Country ‘blog, Monthly review article by Lehlohonolo Kennedy Mahlats and Carlos Martinez in ‘Pambazuka news