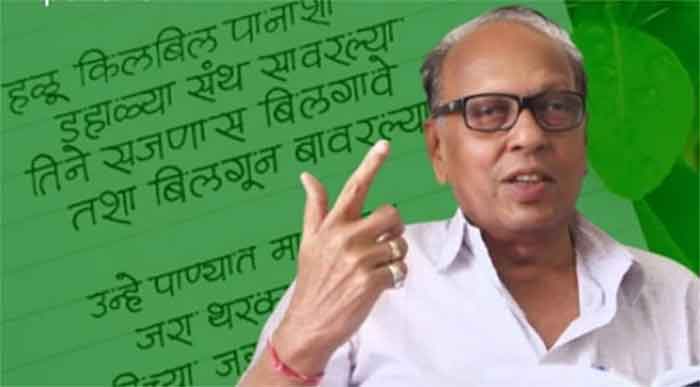

Celebrated Marathi poet N.D. Mahanor, who passed away last month, lived all his life as a farmer in a small village Palaskheda, five km from the famous Ajanta caves in Aurangabad district.

What created and sustained his interest in poetry in this isolation ? We forget that at least some of our rural life has a very vibrant cultural life, there is a long living tradition of various poetic forms and folk poetry and drama, music and dance. In other states like Rajasthan it could also be painting and handicraft and so on.

Mahanor recalled that he imbibed poetry in his very childhood when he sat on his mother’s lap as she instantly composed and sang songs while grinding grains on the stone wheel.

That apart there was so much folk song and music around me, he said. The neighbouring district of Jalgaon produced a wonderful poet Bahinabai in the 19th century. She too would similarly compose songs while grinding and these were fortunately noted down by poet son Sopandev Chaudhari. After her death, he took out the manuscript and showed this to renowned writer Acharya Atre who instantly declared it as a treasure. Today, she is a household name in Maharashta. There must have been many such talented poems in rural areas who were never discovered by the public.

Mahanor always dressed in a simple white shirt and pyjama in his life of 82 years and had little formal education. But he learnt from life, he was distinguished as a poet who brought to life the world of the farmer, poets before him had written about nature more in a romantic way about flowers, birds and trees.

He saw the whole connection between the farmer, the soil, the season, environment , climate , the aesthetics of farm and agriculture. He mentioned to Arti Kulkarni, journalist, about this aesthetic. This is an important point that needs to be stressed, there is widespread aesthetics out their in life. Our ruling class, in its complete and deliberate break with nature, which it wants to exploit, emphasises the aesthetic of art galleries, museums and so on, ignoring the beauty of nature, often it destroys this beauty.

Mahanor attracted attention as a poet even as a teen ager. P.L. Deshpande, prominent cultural icon, was so impressed he obtained his address from literary editor Ram Patwardhan, wrote him a warm letter in 1966.

After that for decades writers kept visiting his farm, staying there, spending time with him, hear him sing, he had a good reciting style. There is a good television recording of his conversation on his farm with Jabbar Patel, film director, Vijaya Rajadhyaksha, noted literary critic and short story writer, Ramdas Bhatkal , publisher, and Chandrakant Patil, writer in the Doordarshan feature Pratibha ani Pratima. His songs became a hit in Jait Re Jait, Jabbar’s feature film on Adivasi life and in other films.

Writers spread over generations, politicians from Y.B. Chavan to present ones, became his fans. He was nominated to the legislative council where he made a good impact with his expertise on agriculture.

No one is more close to nature than a farmer , he is our best link to nature and who could better interpret these issues than a poet farmer like Mahanor. But nature and farm life is now seriously threatened by the pernicious lobby of agri business and chemical fertilisers. We need to rescue the farmer and agriculture from these elements.

Mahanor’s work should also inspire us to take a fresh look at the poetry related to farm life as of Robert Frost, Robert Burns, Wendell Berry and the thinking of eminent critic John Berger and Japanese farmer and philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka and novelist Tolstoy.

As for Robert Frost, some of the best-loved poems in the English language are associated with the small farm owned by the poet from 1900-1911. Here Frost farmed, taught at nearby Pinkerton Academy and developed the poetic voice which later won him the Pulitzer Prize for poetry four times and world fame as one of our foremost poets.

No place played a more vital role in the poet’s life than this 30-acre farm with pasture, fields, woodlands, orchard and gentle spring. This jewel of a literary landmark represents a special era in the poet’s life because it was here that he decided to write poetry…without reassurance of publicity or public acclaim…and despite years of rejection from the literary establishment. For ten long, lean, and hungry years, Robert Frost worked his small farm and taught English at Pinkerton Academy, all the while gleaning from his poverty, hardship, and heartbreak, the essence of his literary geniu

Fukuoka believed that the farmer must write – poetry, songs and stories of the joys and sorrows of life. For who could be better equipped to write than the farmer? Who observes the change of seasons, the brightness of the stars, the formations of the clouds and the fragrance of rain in the air as astutely as the farmer? Who could fathom the moods and shades of mountain, sky, earth and rivers to create a masterpiece of art, if not a farmer? Who could speak of love more eloquently than a farmer, whose proximity to the elements of nature gave him an advantage – to equate his emotions to the changing seasons, the mystery of rain clouds, the flight of birds and the unfurling of a tender bud?

What Fukuoka is most concerned with when it comes to poetry, however, is its sudden disappearance from today’s culture—and he sees this as a direct result of current agricultural practice. In The Road Back to Nature he laments that “there is no time in modern agriculture for a farmer to write a poem or compose a song.” If the modern farmer has lost the time for poetry, then surely there is something wrong with the way he is farming. And if he no longer knows how to create poetry, then he has lost a valuable tool for the restoration of farming in concert with nature—specifically, form.

Scotland’s most famous son Robert Burns was a farmer who wrote his best work at night in his but’n’ben after a day’s hard toil in the soil.

Burns wasn’t the first agriculturist to put pen to paper, but he did set a standard in poetry for self-taught writers describing the landscape from an embedded perspective. There’s a great distinction between these poets, who, because their survival depends on it, have a far more intimate relationship with the land, and those who describe it while looking at it from their firesides on the other side of the window. Chief among the latter are the (largely classically educated) Romantics, who, though drawing inspiration from the landscape, romanticised it in a way a farmer never would. (Wordsworth at least had the gumption to recognise this gulf between romance and reality in The Leech-Gatherer).

John Berger, renowned critic, who taught us how to see and understand art work and life around, in later life chose to live in isolation on a farm in the Alps and write on thee life of the village and the farmer. When invited to his friend John Berger’s house for dinner, a writer once found himself seated between very different houseguests. On one side was a local plumber; on the other, Henri Cartier-Bresson. It’s an image that neatly captures the two abiding interests of Berger’s career. Ever since he began publishing provocative Marxist art criticism in the 1950s, he has written with unparalleled insight about both aesthetics and politics, about the most refined artists and most marginalized communities, about, as he himself put it, “the enduring mystery of great art and the lived experience of the oppressed.”

Actually, Berger has made it his business to kick down the walls between the two. His seminal 1972 television series Ways of Seeing—now a standard art history text around the world—more or less invented cultural studies, and did so in plainspoken language accessible to the public.

Although Tolstoy grew up in aristocratic society, he became disillusioned by the artifice and pettiness that dominated this world. While Tolstoy was writing Anna Karenina, he was developing his own philosophies of nonviolence and anarchism: he believed that people, not government bureaucracies, should take care of each other. Throughout his later life, the wealthy Tolstoy rejected his Russian noble background and dressed in peasant clothes. In the discussions of farming and peasant life that form a large part of Anna Karenina, Tolstoy the philosophical and political turmoil in the rapidly shifting landscape of 19th century Russia.

Tolstoy devotes long passages of Anna Karenina to descriptions of Levin’s farm and the routines of rural life in 19th century Russia. These sections of the novel serve as a sharp contrast to the urban world that Anna Karenina inhabits.

Wendell Berry poet, environemtnalist , in his book The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture (1977) analyzes the many failures of modern, mechanized life. It is one of the key texts of the environmental movement. Berry has criticized environmentalists as well as those involved with big businesses and land development.

Berry strongly believes that small-scale farming is essential to healthy local economies, and that strong local economies are essential to the survival of the species and the wellbeing of the planet.

The central theme of his poems is the return to simplicity and living in tune with the earth. Berry’s ideas echo those of Emerson and Thoreau, but his message is more personal and urges us to engage with the issue more urgently. In the essay “The Loss of the Future”, Berry says: We have reached a point at which we must either consciously desire and choose and determine the future of the earth or submit to such an involvement in our destructiveness that the earth, and ourselves with it, must certainly be destroyed. And we have come to this at a time when it is hard, if not impossible, to foresee a future that is not terrifying.

“Rural America is a colony,” Berry wrote, “and its economy is a colonial economy.

We need more creative writers and experts to write in relation to the serious agricultural crisis in India. That would be a good tribute to Mahanor.

Vidyadhar Date is a senior journalist, culture critic and author of a book on public transport