Dr. Ambedkar had exposure to Buddhism early in his life by means of a Marathi book on the Buddha gifted by one of his teachers. Yet his path to formally adopt Buddhism followed a long process that brought together several strands in his life-journey. They comprised his life-experiences, his deep investigation into the institution of caste as part of a social and religious order, his education in Western social and political thought – and his profound study of Buddhism itself.

How one reads religious texts is of course a matter of contention. But a certain amount of faith – shraddha – forms the bedrock of following most texts which could be classified as religious i.e. pertaining to a religion. Ambedkar quite evidently read all religious texts – Hindu or Buddhist – as human creations. He analysed them for their ideas of society, equality, justice – and their methods of following a moral life for spiritual growth. And it was these ways of looking at texts and practices that gave him the various insights that he employed in his arguments for choosing the Buddhist path eventually.

His life-experiences of segregation and discrimination, even as the instincts of someone young, were probably his first teachers. He protested against the reading of the Hindu epics early on, something which his father carried out at home. This is a remarkable insight by someone young and also remarkable that he was able to articulate his feelings of what he perceived as injustice contained in those texts. So, while his father probably did not feel entirely separate from the wider Hindu religio-cultural world, finding it acceptable and even beneficial to ritually read the epics, the young Ambedkar had developed some sense of distance, alienation and a critical attitude from an early age. He had the courage and conviction to question a practice – that of reading Hindu epics – within his own family.

His formative years and preliminary education in India probably gave him enough insight into the realities of the caste system. When we find him at Columbia University, we come across what was probably his first essay for an anthropology class, “Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis, and Development.” In it we see a young scholar exploring the various theories then current about the origins of the caste system. Ambedkar tests each theory for its soundness and in the end rejects them all as being inadequate to describe how castes formed. He then boldly advances his own ideas on the formation of this institution. This reflects a fast-maturing thinker who has the courage to analyse existing ideas and put forth his own. The seeds of his subsequent analyses of Hindu social organization and the Hindu religious life had begun bearing fruit. His study of areas such as social institutions and social organization, Economic History, Moral and Political Philosophy, Primitive Religions, and Liberty & Democracy, gave him the depth of knowledge he later put to use in his razor-sharp critiques of Hindu social and religious ideas.

In Buddhism he found an uncompromising ethical code which left no scope for moral ambiguity and ethical compromises. His review of the philosophy of the Marxists in his lecture, Buddha or Karl Marx, brings together his education in Western democratic and socialist values and his views on the Buddha’s practical teachings and his monastic establishment. Ambedkar states that while the world much admired the French Revolution for its aims of Liberty, Fraternity and Equality, they were not delivered by that revolution or by the Communist Revolution in Russia. “It seems that the three can coexist only if one follows the way of the Buddha. Communism can give one but not all,” he concludes in the lecture. But of Buddhism’s unique value, he states: “It is clear that the means adopted by the Buddha were to convert a man by changing his moral disposition to follow the path voluntarily.” But as for the Communists, Ambedkar felt that “[t]he means adopted by the Communists are equally clear, short and swift. They are (1) Violence and (2) Dictatorship of the Proletariat.” He elaborates on his disapproval of the Communists’ methods further in his lecture.

But it is clear how Buddhism offered the most rational and beneficial form of spiritual path that he felt human beings needed. He was convinced that human beings needed spirituality to grow: “Man must grow materially as well as spiritually.” And the Buddha’s teachings contained the moral richness and message that could train men in morality and righteousness: “What the Buddha wanted was that each man should be morally so trained that he may himself become a sentinel for the kingdom of righteousness,” he observed.

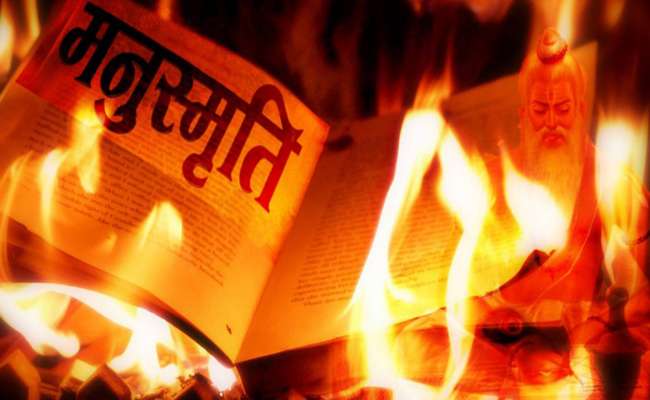

Since that was his reading of the Buddha’s teachings – his Dhamma – it seems fair to conclude that he did not find such an unequivocal message for a moral and just pursuit of life in the Hindu texts. But there was another aspect to it. He observed first hand in his experience the living practices of Hinduism which he chalked up to a rigid and implicit belief of the Hindus in their sacred texts, their shastras. If the teachings of the shastras resulted not in a moral elevation of those following them but in a debasement of their ideas of morality and justice, then what good could the system be which was based on those shastras? It is not surprising that Dr. Ambedkar expressed these views in uncompromising fashion in the text of his speech, the Annihilation of Caste, wherein he advocated for the jettisoning of these shastric bases of Hinduism for a fresh start.

The reaction to just the text of his speech, with his appearance being canceled, confirmed him in his conviction that the Hindus did not want a systemic change and moral probity was not their priority.

Yet, Ambedkar opting for another organized religion to convert to after opting out of Hinduism shocked many of his contemporaries. Many of them saw him essentially as a secular, liberal person, too steeped in ideas of Western democracy and rationality to take to religion easily. Some of them had themselves advocated paths of atheism or agnosticism. Others were more convinced by various socialist philosophies.

But Ambedkar surely had realized that he was a leader of the oppressed classes and he had to show them a path. As scholar Ajay Skaria notes, “Ambedkar converts to Navayana Buddhism precisely as an act of the greatest responsibility..not only as an abstract individual, nor even as an individual Dalit, but also as a Dalit leader…as one whose actions form a collective Dalit or Mahar identity.”

This path had to have a solid moral foundation; a path not dependent on rituals, a path which prized and employed a rational way to understand and propagate its principles. It was also to be a path with a well-established history, with cultural dimensions and a rich legacy of debate and discussion. Above all it was a path with an existing system in place, a support structure that the people he was leading could make use of, as they themselves became educated in the ways of the Dhamma.

But in choosing a path, that of the Buddha’s Dhamma, Ambedkar was not just trodding the old path. He was, in ways that were his wont, charting a new course. He had bravely reinterpreted the Buddha’s popular biographical story, especially that of his renunciation in his book, Buddha and His Dhamma. His study and practice of Buddhism was not as a monk. He continued his engagement with it amidst his social and political endeavors, and alongside his struggle to seek out equality and fraternity in the larger society he was part of. His lived experiences once again informed the choice of the social, religious, cultural and spiritual world he wished to assume, and wanted his brethren also to be a part of.

So, it is hardly surprising that his decision to adopt Buddhism formally had social and political dimensions as well. But it was a decision which arrived at after exhaustive engagement and soul searching. He reformulated some basic principles and the Wheel-turning – the Dhammacakka-Pravartana – of the new order, the Navayana Buddhism, was infused by his being – political, liberal, secular, spiritual.

Umang Kumar is a social activist based in Delhi NCR