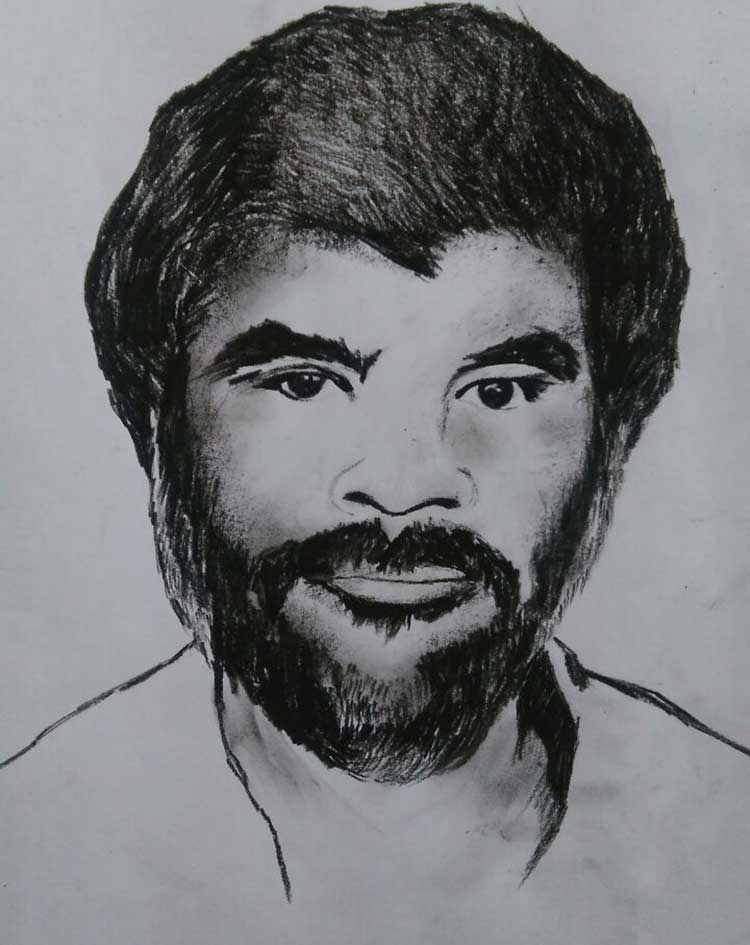

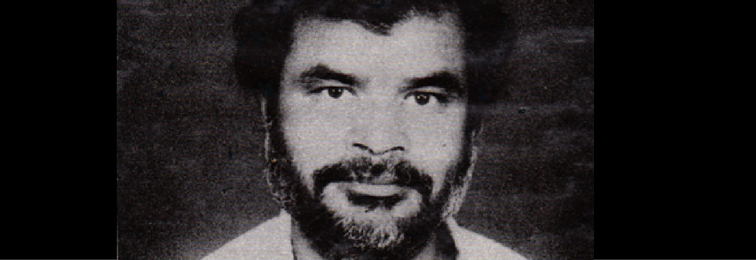

Before 28th September 1991, very few people outside Chhattisgarh or Madhya Pradesh knew the name of Shankar GuhaNiyogi. On this day, along with Niyogi’s name, people also learned the phrase, “sangharsh aur nirman”, i.e. “struggle and creation”.

What is ‘struggle and creation’? In the context of a fight for rights, struggle is easy to understand – it’s striving. What about creation? Some have labeledNiyogi a “revisionist” because he has spoken of creation, others have called him “the Gandhi of Chhattisgarh”. Gramsci fans have found indications of his thinking in the theory of struggle and creation. (We know Niyogi never had the opportunity to read any of Gramsci’s work. There was nothing by Gramsci in his huge collection of books.) The Bengali Naxal leader AzizulHaque has ridiculed the term “struggle and creation” again and again in his satirical fictional portrayal (“Haatikhonje raja”) of the Kanoria workers’ movement that had some basic commonality with the Chhattisgarh workers’ struggle.

The revolutionary poet Samir Roy said, “Many either do not understand or do not want to understand the theory of struggle and creation.” According to him, “the idea of struggle and creation is an original contribution to social science. After Marx-Engels-Lenin-Stalin-Mao, this theory points the way to a new direction in social science.”

In an interview in 1989, Niyogi said, “In order to change the organization of society and to win rights we need struggle and small acts of creation that will awaken new consciousness about alternatives. We are experimenting with this. We must keep in mind, however, that the goal of the politics of struggle and creation is replacement of this anti-people exploitative system.”

Niyogi was a Marxist-Leninist. His contemporary, the labour leader A.K.Roy said, “Beyond the three streams of the communist movement in this country (i.e. CPI, CPIM, CPIML), Shankar GuhaNiyogi represented a fourth stream. This stream was one of integration.” Selecting the essentials from experiments of the past, Niyogi devoted his life to the creative application of Marxism-Leninism on the ground in Chhattisgarh in a way that was suited to the time and the place.

Forty years after the working class of Russia took over state power through the November revolution, the Soviet Union took the path of social imperialism. Less than twenty years after China overthrew exploitation in 1949, Mao Tse Tung noticed the corruption in the working-class party and had to call upon the people to “bombard the headquarters” – the cultural revolution began. After Mao’s death, China followed in the footsteps of the Soviet Union. All these events concerned Niyogi like it did other devoted communists – what then was the right way? Would the power that was gained through blood bath and the sacrifices of working people return again and again to the exploitative class?

In fact, uprooting the exploitative class by force and taking over state power and control over the economy is a relatively easy thing to do. Far more difficult to achieve is the change in consciousness. That is why, even those in the vanguard party, communist party leaders and representatives elected by the people, fall prey to capitalist thinking and lead the workers’ state astray. An unrelenting struggle must be waged against this. Mao Tse Tung said – we need not just one cultural revolution but thousands of cultural revolutions in order to achieve an egalitarian society.

Niyogi’s originality lies in the fact that he moved away from the idea of a revolution followed by a cultural revolution and experimented with something new. Based on the negative experiences of the past, he understood that a change in the economy does not automatically lead to a change in culture. He therefore broached the idea of a cultural change that is fostered in parallel with the class struggle and the struggle to reform society. In other words, the cultural revolution begins with the beginning of the struggle.

The experiments that began soon after the birth of the Chhattisgarh Mines ShramikSangh in 1977 were later formalized and adopted as part of the platform of the Chhattisgarh MuktiMorcha in 1987 under the rubric of “the politics of struggle and creation”. Niyogi did not claim any infallibility for this theory, rather he presented it as a hypothesis.

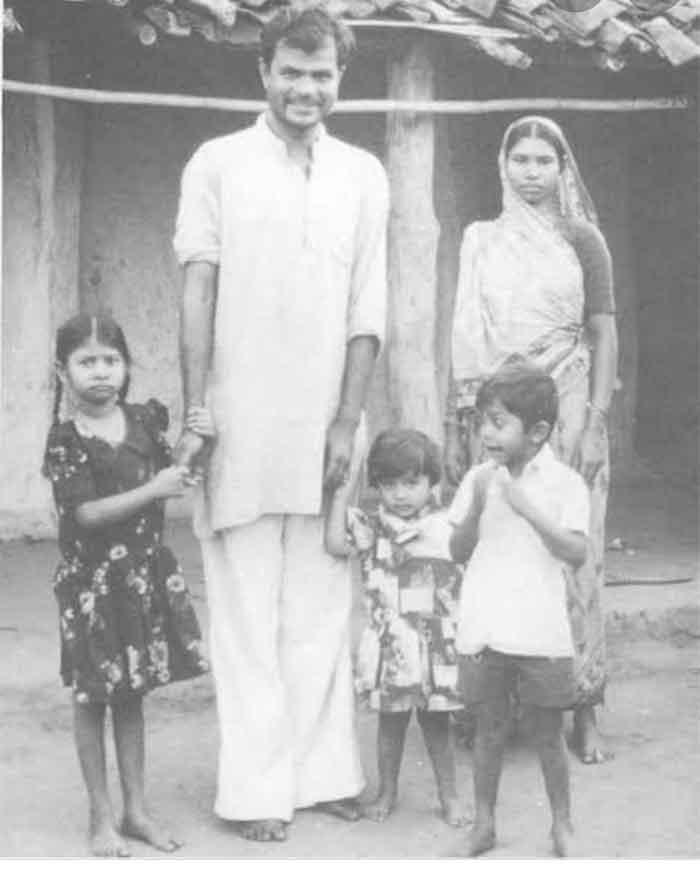

Chhattisgarh MuktiMorcha had the slogan – “Creation for Struggle and Struggle for Creation”—ceaseless struggle for the creation of a society without exploitation and, for the sake of that struggle, creation. A society without exploitation cannot be established without revolution. Nevertheless, small scale experimental creative activity can bring to life examples of a non-exploitative society and inspire people to take part in the struggle for change.

In the laboratory of Dalli-Rajhara, one experiment took place after another –

- The health movement, through Shaheed Hospital, demonstrated how healthcare can be delivered in a new society using new modes of treatment, health education, new ways of running an organization, and in connection with social movements.

-

The education agenda included six primary schools and adult education run by the workers’ organization.

-

The new democratic culture was disseminated by “NayaAnjor” (light of dawn).

-

The consciousness of the working man was liberated from the daze of addiction by the anti-liquor movement.

-

The fight to establish semi-mechanisation as an alternative to mechanisation of the mines pioneered a way to improve quantity and quality of production without retrenching workers in a populous country like India.

-

The environmental project “ApnaJangalkoPahchano” (know your own forest) demonstrated what forest policy could be like in a non-exploitative society.

There were many more experiments like this.

The creative/constructive work in Chhattisgarh had the following characteristics –

- Alternative ideas were brought to life through mass struggle.

-

The working people directly established and managed the alternatives.

-

The alternative institutions grew step by step based on local effort, not through dependence on external grants.

-

The alternatives established by the efforts of the working class served people of other oppressed classes.

-

The alternatives not only inspired new popular struggles, they were intimately connected to ongoing popular struggles.

-

The constructive efforts served as workshops to fashion humans with new awareness and new values.

One might point out that, once the class struggle intensified, such creative ventures could easily be crushed by the exploitative class using the machinery of the state. True, institutions can be crushed. What cannot be crushed, though, are new values and a newly developed revolutionary consciousness.

Many people think that all a revolutionary does is fight, and fight some more. They see constructive work as tantamount to revisionism. It is therefore important to understand the difference between revisionist constructive work and revolutionary constructive work.

Niyogi was well aware of this. I will recount the essence of the discussion that took place at the first anniversary of the health agenda, the most significant of the constructive ventures.

- The goal of revisionist reform is to subdue class struggle by giving a few handouts to exploited people. In contrast, revolutionary social reform aims to intensify class struggle, to intensify popular repugnance for the exploitative system. Reform is not its ultimate aim, the ultimate aim is to transform the society. Revolutionary reform functions as part of revolutionary political struggle.

-

Social reformers who undertake revisionist reform are cut off from the primary stream of popular struggle. The bedrock of revolutionary reform is the political consciousness of workers and peasants, their combined strength and creativity.

-

Revolutionary reformers are aware of the ultimate futility of their agenda since the social problems they are trying to fight are rooted in the current social structure. Very little progress can be made without changing the structure of society.

The fall of socialist strongholds one after another did not dishearten Niyogi as it did other communist revolutionaries. Unlike others, he did not stop at analyzing the cause of the devastation, he went further and tried to find ways to respond to it. Learning from past leaders in social revolution and using his own experiences in struggle, he experimented with “SangharshaurNirman”. He wanted to create people with new values for a new society by linking class struggle to the fight for a transformation in consciousness right from the start.

The untimely loss of Niyogi to the class struggle has certainly harmed the experiment in “Struggle and Creation”. It is up to those of us who wish to transform society, and after transformation build a new society, to further this unfinished experiment – if not at the grand scale that Niyogi envisioned, at least to the best of our abilities.