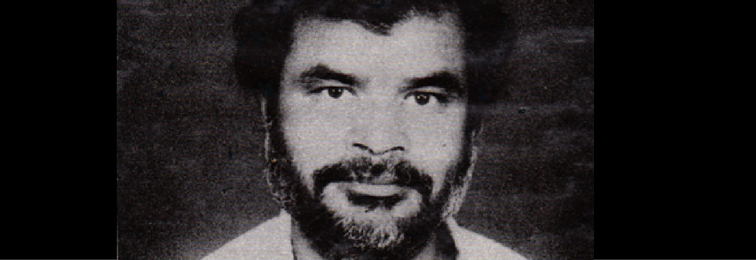

Today on September 28 many, many people in Chattisgarh and other parts of India will be remembering Shankar Guha Niyogi on his death anniversary. It was on this day that he was assassinated at the peak of his efforts to mobilize workers for a big struggle.

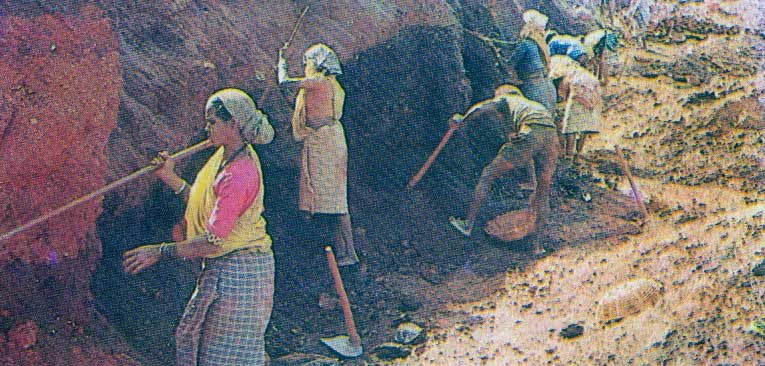

Niyogi, a labor leader who became a legend in his lifetime, led a very creative trade union movement among iron ore miners of Central India during 1977-91, combining livelihood struggles with a health program, educational work, and a range of social reform and cultural regeneration activities. He broadened the trade union movement to link it closely with many-sided struggles of peasants in nearby villages, mostly from tribal communities, whether for land and forest rights or against pollution of water sources. Hence he was widely recognized as a highly creative labor leader who combined struggles with constructive activities ( sangharsh aur nirman).

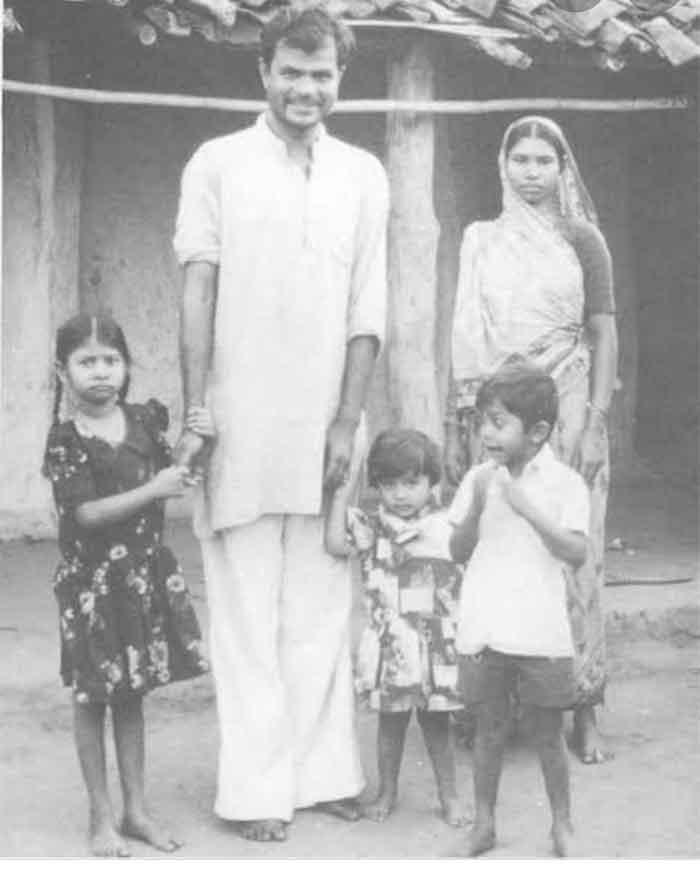

Niyogi was active earlier as a student leader in college and coming from Bengal to work in Bhilai Steel Plant in Chattisgarh region, he gave up a promising career to merge entirely with the poorest, neglected sections of miners, moving from village to village, mine to mine, taking up odd jobs but all the time trying to understand his people and their problems. Along the line he was married to Asha, who worked in a mine, and henceforth they also became partners in various struggles.

In the early phase of the struggle workers could get some wage gains but the question of avoiding unemployment caused by mechanization was a bigger challenge. Here Niyogi showed his great creativity and ability to respond to complex issues with innovative thinking. The foremost union led by Niyogi ( Chattisgarh Mines Shramik Sangh–CMSS) resisted heavy mechanization by arguing that the technology adopted by a country should be in keeping in with the conditions prevailing in the country. Heavy machines and total mechanization may be all right for those countries where loss of jobs caused by them is not a problem, but not for a country like India where unemployment is a big issue. Documents prepared at that time by the union reveal a very appreciable understanding of the complex debate. This understanding is close to the understanding of Mahatma Gandhi who had strongly argued against machines which disrupt and destroy livelihoods.

The CMSS prepared an alternative plan of partial mechanization which would protect jobs and also take care of quality control aspects. On this basis the union was able to protect mining jobs for a longer period.

A lesser known aspect of Niyogi is his firm faith in communal harmony and his union was active in protecting minorities or any victims of sectarian, targeted violence.

The anti-liquor movement of the CMSS is still remembered as one of the largest collective voluntary giving up of liquor, involving thousands of miners. This not only protected the health of workers and reduced domestic violence, but in addition led to purchase of diverse goods by workers for themselves and children, and thereby contributed to sudden upswing in the local market after the workers had experienced wage rise by given up liquor around the same time.

Successes of workers were annoying several dominant persons of the area, including liquor sellers. Things became even more difficult when Niyogi moved from the mining belt to the nearby Bhilai industrial belt to fight the battles of the workers employed by several leading private industrialists of the area. They were more aggressive towards workers and had closer relational with criminal mafias.

Once the BJP government was installed here led by Sunderlal Patwa as Chief Minister, the attacks on workers became more frequent. As a journalist I had reported on several such attacks at that time. Niyogi realized that his own life was under threat. He even recorded a last statement which indicated this. He then went with several workers to Delhi, and met the President of India and others. On 28 September 1991 a hired goon fired on him when he was sleeping peacefully after a very tiring day. His death sent shock waves throughout the country. Workers gathered in huge numbers to bid a very tearful farewell to the leader they had loved so much, elders weeping endlessly like they had lost their own child.

While the first court hearing this murder case sentenced two top industrialists along with three others to life imprisonment, they appealed against this decision, finally going back to their luxury life quickly enough.

The assassination of Niyogi was all the more tragic as Niyogi himself had striven hard to keep his movement non-violent despite grave provocations from time to time. His death was a very big blow to the spread of a very creative and innovative trade union movement, linked well to villages around industrial-mining belts, which had shown great promise. Niyogi died at the age of only 48, but his work still lives on in several struggles and efforts which draw inspiration from him.

Bharat Dogra has contributed about over one hundred articles, reports and a few booklets on Niyogi-led movements. His book Another Path Exists is dedicated to Niyogi Ji. His other recent books include Protecting Earth for Children, A Day in 2071 and Earth without Borders.