by Pranab Doley, Jacinta Kerketta, Deme Oraon, Gladson Dungdung, Sharanya and Rajaraman Sundaresan

A recent protest, through a petition endorsed by around 300 Adivasi leaders, academics, activists, environmental groups and people’s movements in India, has brought the issue of decolonization to the forefront by protesting against the decision of IUAES and its member organizations to hold the World Anthropology Congress (WAC), 2023 at Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences (KISS), Odisha India, which refers to itself as the world’s largest anthropological laboratory. It is important to note that some of the world’s leading advocates on decolonization like Arturo Escobar, Gustavo Esteva and Boaventura dos Santos have endorsed this petition along with many leading academics, scholars, writers and activists like Virginus Xaxa, Ashish Kothari, Ruby Hembrom and Nandini Sundar,KISS clearly indicating a shift in terms of the need for challenging the global coloniality of knowledge. What does an ‘anthropological laboratory’ for Adivasi people mean at a time when many universities and student protests across the world, particularly in South Africa and other European countries, are emphatically engaging and arguing for decoloniality not only from the perspective of territorial independence alone, but also for economic, epistemic, spiritual and cultural independence.

A letter dated 16th August, 2020, from the President, IUAES and its Secretary General, states that “after following a careful consultative process at various levels, the IUAES Executive Committee deliberated and decided to withdraw its collaboration with KISS regarding the organization of the 2023 World Anthropology Congress” and it further clarified that “this decision was arrived at without prejudice with respect to the workings of the said institute”. It is indeed a welcome step. In a recent article, anthropologist, Prof Abhijit Guha analysing the discourse around the hosting of WCA at KISS writes that “the Indian anthropologists have failed to generate real academic debate in the public domain around the anthropology and sociology of factory schools and their relationship with the large-scale economic deprivation of the Adivasis caused by mining, deforestation and industrialisation in the context of Hinduisation of the Adivasis in India” and this today he says is “a tragic outcome of public anthropology in the country.”

Why KISS?

KISS claims that it is the world’s largest boarding school-cum-university for Adivasi children. It is founded by a businessman turned politician of the current ruling party (Biju Janata Dal) in Odisha, Mr. Achyuta Samanta (an ex-member of the University Grants Commission), who has referred to Adivasi people as “people who live just like animals with animals in the dense forest”. Statements like these at one stroke not only de-humanize the Adivasi people but disinherit them from the rich knowledge societies they are born into. This tells us about our own colonial psychological self that continues to thrive within us and stands exposed when we come to defining ‘the other’. In a casteist society like ours, the brahminical mind becomes an extension of the colonial self as a psychological category of the mind. The violent passion to civilize the savage or the primitive (sic!) stems from our colonial-self by extending the colonial gaze through a pedagogy of assimilation which displaces the Adivasi children and their futures and their epistemic realities in the name of education for development in the contemporary times.

KISS in many ways embodies the perfect dialectic between education and development – two powerful concepts, which have escaped exorcism in the way they are interlinked in a country like India where most of the anthropologists, scientists, educationists and developmentalists resist rethinking the idea of education and development beyond the broader global coloniality of knowledge. And it is in this context that we situate KISS, which is a victim, but glorifies itself as a pioneer of social evolutionism where the institute’s aim is to transform Adivasi children who are social liabilities into social assets through the process of education. Mr. Samanta in many interviews has said that, “the tribal children earlier were liability to the nation and now through KISS we are turning them into assets.”

As Linda Tuhiwai Smith argues in her book ‘Decolonizing Methodologies’, that the continuing memory of imperialism has been perpetuated through the means in which knowledge about indigenous people was collected, classified and then represented to western audiences, and then through the eyes of the west, represented back to those who have been colonized. It is within this circularity of what we call the western epistemic trap that institutes like KISS are fixated with a single narrative about the Adivasi people. In fact, institutes like KISS and its founder must understand that it is the western discourse about the ‘other’ that they are perpetuating by using their vocabulary, reports, and letters in their defence against the critique of coloniality.

Extraction education

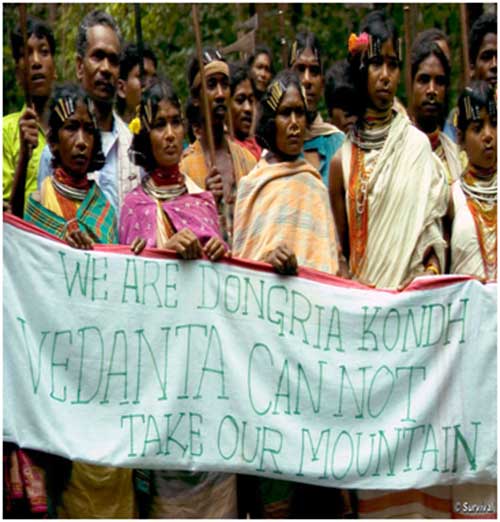

In the year 2012, when the Dongria Kondh community was resisting severe oppression and battling invasion by the UK based Vedanta Corporation, which had planned to mine the sacred site of Niyamgiri hills, KISS entered into an agreement with Vedanta Foundation and Vedanta Aluminium Limited for mainstreaming 100 Dongria Adivasi children from their project area for providing value based education. Is it not absolutely paramount to critically understand and question the integrity and ethics of this institute, which was trying to “instil educational values” into Dongria children by providing them education at KISS under the financial commitments it had made to Vedanta? Just four months after signing this tripartite agreement, IUAES, jointly with KISS, organised its Inter-Congress 2012 on the theme “Children and Youth in a changing world” at KIIT university (an industrial technical institute also founded by Mr. Samanta). A report about this Inter-Congress in 2012 co-written by the current Vice-Chancellor of Sambalpur University (also one of the partners in hosting the WAC), says that more than 300 participants from 47 countries visited KISS – the largest residential educational institution for Adivasi children… with great interest and enthusiasm. A cultural programme was staged by the children of KISS for the entertainment of the guests.”

Can some of these members who were ‘entertained’ (mostly anthropologists) by Adivasi children at KISS humbly reflect upon themselves as anthropologists and tell us what was the “educational value” that KISS instils amongst the Adivasi children? It seems that a serious sub-discipline namely anthropology of childhood was being discussed at this venue and yet at the same time Adivasi children were being indoctrinated there with ‘educational values’ sponsored by the very corporation which was robbing the children of their histories, identities, lands and futures.

The dialectic between education and development that the KISS model engages in can be best understood if we look at the number of MoUs KISS has signed with some of the major extractive industries in Odisha and India like Vedanta, Adani, Tata, Nalco, NMDC, REC etc who are today feeding off Adivasi lives and lands. The serious question that is being raised by Adivasi leaders, environmentalists and people’s movements who are protesting and resisting the WAC from happening at KISS is a question of epistemic freedom – structural, socio-cultural, and spiritual. An ex-student of KISS, who decided not to continue his education there although he had opportunities to pursue his post-graduation there, had terrible experiences while studying at KISS and raises a very pertinent question – “why are we as Adivasi people always subjected to accepting the beliefs and value systems of a dominant society? Don’t we have the right and freedom to define what education and development means to us as a community and as a tribe?”

Schools like KISS disinherit our children from our history and struggles, says Lado Sikoka, leader of the Niyamgiri movement, who is deeply concerned that the children in Niymagiri have to migrate hundreds of kilometres to study in residential schools. An Adivasi parent of KISS who is also at the forefront of resisting the expansion of Nalco mines in Koraput district says, “I was completely unaware of the arrangements between KISS and Nalco in supporting our children’s education. Now, how can I hope that my children will continue the same struggle resisting the forceful takeover of our lands for mining?”

The larger question that we want to raise through this collective movement against KISS is, “how can a model which sells itself as an institute for Adivasi people’s education partner with mining corporations that are killing our Adivasi people and stealing their lands for profiteering? Rather than helping the communities and children question this corporate loot of resources, is the institute forging ties with these corporations to decide the fate of our children by indoctrinating them into a future where they no longer belong to the forests?” – forests not as ‘wilderness’- but as rich spatial-identities of knowledge societies.

The very existence of KISS is an extension of the continuing legacy of internal colonialism if we particularly look at the history of development in India. From our long years of interaction with Adivasi community leaders, activists and academics, several questions flash before us, pushing us to enquire deeper into what KISS stands for, and what are its impacts on the futures of Adivasi communities. We continue to ask and look for answers to these questions …. Where in the world do you find a single institution holding more than 27,000 Adivasi children? Is that even human? How can the KISS education model be holistic and cater to its more than 27,000 Adivasi children who belong to over 62 tribes, including 13 particularly vulnerable Adivasi groups, that all have different value systems, cultural practices, languages, political and customary institutions, by following a unilinear pedagogy of the Odisha state board syllabus? Just merely showcasing a multi-lingual language laboratory at KISS won’t do! It is also equally important to understand that every language, irrespective of whether it has a written script or not, has its own worldview, rich tradition of values, customs and bio-cultural systems of knowledge that geographically underpin the language, its politics and cosmology.

As Adivasis and as friends who have deepest of concern for Adivasi people, we would like to ask the Indian government, the Ministry of Tribal Affairs and the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes whether they realise that by honouring KISS with a leadership award they have blatantly outsourced their responsibility promised under Article 46 of the Indian constitution, which states that the State shall promote with special care the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the society and in particular of the Dalits and Adivasis and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation, to private corporations and third party agents like KISS. Will they ever realise?

Adivasi identities and the very being of an Adivasi is closely interwoven with nature. Adivasi philosophy, to a great extent, embeds itself in a worldview that regards nature as sacred. So, we as Adivasi people, environmentalists and concerned citizens ask: “As a model institute for Adivasi education, how can celebration of mainstream Hindu festivals with large fanfare involving students right from Grade I to PG like Ganesh puja, Saraswati puja, Vishwakarma puja be justified? For that matter, how can the display of a Hanuman temple within the premises of the school be justified? What is the idea of sacred that KISS as an institution for Adivasi children follows?”

Decolonization

In the times of unacceptable global injustice, unfettered racism and casteism, growing inequality in the distribution of power and the accelerating climate crisis, the decolonizing education movement, is being increasingly discussed and spoken about in most universities across the world as a doctrine of total freedom for the hitherto oppressed peoples. In many ways, decolonization movement is an attempt to depatriarchize the hegemonic authority of the west as teacher of the world and further to demystify the power the west holds over defining ‘what is knowledge?’ to the rest of us.

For most of Asia, has colonialism ever ended? Colonialism, many scholars have said, needs to be seen in three interrelated and overlapping categories- institutional, structural, and epistemic. Colonialism does not end when the colonizers leave and as the South African scholar Sabelo Ndlovu–Ghatsheni, puts it “It operates like an intimate enemy and sits within you as a parasite. In other words, if you remove colonialism physically without removing it epistemically, it will not disappear.”

We strongly believe that questioning factory schools like KISS, along with its allied anthropological institutions, opens a window in creating a larger community led dialogue and public discourse which exposes and lays bare the injustice, systemic inequality, deaths, suicides, sexual harassment and epistemic alienation that Adivasi children have been facing since generations in the name of schooling and education. The need for such a critical enquiry is also felt deeply because to a large extent, the colonial nature of anthropology in India seems to resist engaging with the rise and legitimisation of factory schools as sites of propagating and sustaining coloniality. Factory schools like KISS have built such powerful and impressive political and social capital that it almost looks as if questioning their deep seated framework of coloniality is an act of undermining the dominant societies’ claim over social evolutionism that it has perpetually subjected upon the Adivasi people and their futures. It is important also to emphasize that there is little difference between the colonial gaze of the civilizing mission of government schools, private and religious based schools and factory schools like KISS for Adivasi children, because of the inherent pedagogical biases that these institutes of education have towards Adivasi identities, knowledge systems and cosmologies.

Enough is Enough

There is a dire need to challenge the coloniality of knowledge within which factory schools like KISS operate, in depriving Adivasi people of their right to cognitive justice and epistemic virtue by de-humanising and de-legitimizing them and their societies as people without knowledge. The collective decision to oppose KISS from hosting the World Congress of Anthropology is also to say loud and clear that as a society we shall no longer tolerate being treated as objects of study or experimentation or as people who are subjected by the experts and the dominant society to fight for our rightful existence as people of rich history, revolts and worldviews between a museum and a laboratory.

The role of education in a society is complex and its relationship to development has been historically problematic. The current factory school models like KISS reflect and reproduce the unequal social structure and hierarchical cultures of the dominant groups that control it and reproduce them in Adivasi societies through their pedagogies. It is in this context that it will be important to renew our way of listening to the voices of different groups, particularly Adivasi people, without making them into archaic models of a need for development, and to renew our awareness of their struggles and suffering. Crafting a different future can only be possible when our colonial-self, as victims of global coloniality, begin to understand the nature of our entrapment in the colonial structure of knowledge within which we exist as objects of deceit, oppression and exploitation. This is particularly important in the context of India, where the colonizer is no longer physically visible but still exists as a psychological category within our minds.

Perhaps, this is a small stepping stone towards a larger movement in decolonisation of education as a whole where Adivasi people are no longer seen as people of the past, but as contemporaries who have the right to dream, reimagine, challenge and construct a future on their own terms.

This, we owe to our Adivasi people, who are the best conservationists in the world and have constantly reminded us throughout history what it means to be a democracy.

(This open letter has been collectively written by Pranab Doley, Jacinta Kerketta, Deme Oraon, Gladson Dungdung, Sharanya and Rajaraman from the Stop Factory Schools Network)

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER