(This essay was written in 2015,but remained unpublished. The thing to note is that practically everything it says holds good five years later.)

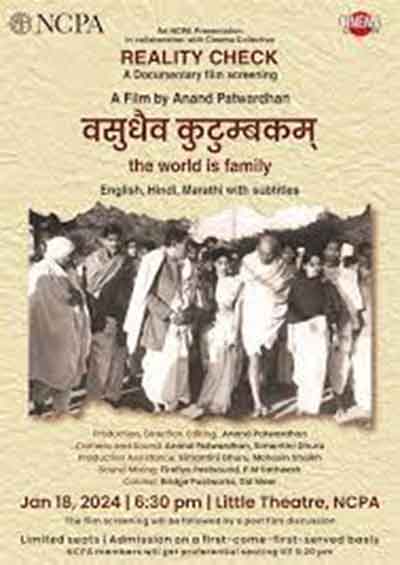

At least three subjects of continuing public interest are on many lips these days – namely, the 40th anniversary this year of the Emergency; the hurried initiatives shown by the Modi government to raise the height of the Sardar Sarovar Dam on the Narmada; and ‘Operation Bluestar’, mounted 30 years ago by the Indian Army against armed occupiers of the Golden Temple in Amritsar. In his documentaries, Anand Patwardhan has dealt with each of these subjects in his characteristic questioning style. As documents of State repression against dissenters of one kind or another, Patwardhan’s films would be hard to beat for their pioneering mix of art and activism.

Arguably, no Indian filmmaker has done as much as Anand Patwardhan to breathe life into the political documentary by liberating it from the stranglehold of official diktat. In fact, if anyone can be said to have pioneered what goes by the name of ‘New Indian Documentary’, it is this Bombay-based astute chronicler of contemporary times who has relentlessly questioned the system through his films, articles, speeches and social interventions. His offerings are regional or national in content but universal in appeal, dealing with a range of issues like lopsided economic development, social inequality, displacement, prejudice and cruelty with a depth of reflection that allows them to resonate well beyond the Indian experience. Coming up with simplistic responses to private tragedies and public debates is not for Patwardhan; rather, he opens up a subject and draws in all the parties involved, generating a layered dialogue that is difficult to ignore. Democracy, otherwise so much in danger these days, breathes easy in his films where everyone gets to have his say.

The political documentary in India came of age with the imposition of Emergency by Indira Gandhi in the dark summer of 1975. Patwardhan’s Prisoners of Conscience (45 minutes, b&w, 1978) deals with this period when practically the entire Opposition was put behind bars. Talking about the film, Patwardhan has said : “I covered socialists like Jayaprakash Narayan and non-violent methods of class struggle, as well as Maoists who were talking about armed struggle. In this naïve and idealistic manner, I put them all into one boat as people who were fighting for justice, which I still believe they were. But there were obviously all kinds of contradictions which I wasn’t getting into. So, in that sense, my ideal was always mixed, somewhere between Marx and Gandhi.”

One has only to look around the contemporary political scene in India to realize the undiminished relevance of Prisoners of Conscience. To be a deshadrohi (traitor) in tolerant, liberal and democratic India, one has only to utter a word of criticism against the repressive State machinery! The case of Binayak Sen is known to one and all because he is, in a sense, a ‘celebrity’, but how many of us have kept count of the thousands of ‘humble’ dissenters rotting away for years behind bars without trial. In that sense, the Emergency is an ongoing state of oppression of nay-sayers and is likely to continue in some form or the other for generations to come. If in one part of the country like Chhattisgarh or Maharashtra, a vocal critic of the system is jailed for being a so-called Maoist, then in another region like Manipur, the so-called offender is shot or beaten to a pulp or held in detention without recourse to law for opposing the draconian AFSPA. Similarly, the suffering parents of Kashmir know only too well what awaits them should they take it into their head to defy the Indian army and the para-military forces, and demand that their ‘disappeared’ children be given back to them.

Patwardhan’s Emergency film was preceded by Waves of Revolution (30 minutes, b&w, 1974). Watching the two together is a unique experience – one dovetails into the other, making for something akin to a historical odyssey through a period in which one political crisis followed another. In both, Patwardhan captured with courage and energy in an idiom suffused with a certain earthy suffocation, the contempt for democracy and rule of law shown by the political class in power. Images of the silent scream of the incarcerated merge effectively with those of official high-handedness, to produce documents of socio-political relevance that have more than stood the test of time.

Patwardhan was only twenty-four when he made Waves of Revolution. His words about the background to the making of the film can be read as an inspiring lesson on a young Indian citizen’s decided response to what he saw taking place around him in the mid-1970s. “In 1974, I’d gone to Bihar to join the movement there, a student movement against corruption. They asked me to take pictures on a particular day when demonstrations were being planned – a big demonstration where there was going to be police repression, so they said : Take pictures as proof. So I went back to Delhi and, instead of a still-camera, I thought I’d shoot it on film. I borrowed a Super8 camera from a friend and took that friend along, and we went and shot that day’s demonstrations. Eventually, we thought we could do more than just have some dramatic footage on the Super8. We projected it on a screen and shot it with a 16mm camera. That became the basis for Waves of Revolution… Then Emergency was declared, and all the people who were in the movement that I was filming were put in jail. The movement was crushed. I could have been in jail as well, but I got a teaching post in Canada to do my Master’s and I smuggled out this film in pieces and reassembled it in Canada, and then started showing it against the Emergency in India.”

Meanwhile, the confrontation some months ago in and around the Golden Temple complex between those who would like to resurrect the misdirected ideology of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale’s message of a separate Khalistan and those opposed to it, brings to sharp focus once again Patwardhan’s Punjab film, Una Mitran di Yaad Pyaari (In Memory of Friends, 60 minutes, colour, 1990). The film examined the terrorism perpetrated by both the State machinery and religious fanatics during the separatist movement in Punjab for a Sikh State. Bringing to life the anti-sectarian writings of the martyr folk hero, Bhagat Singh, Patwardhan underscores the irony of the violence that had come to visit ‘the land of five rivers’.

Patwardhan : “The story of Punjab, and of the film, is also the story of those who never succumbed to religious blind faith or to the false secularism of a corrupt State. In 1931 the British hanged three youths – Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev – all members of the newly-formed Hindustan Socialist Republican Association. Bhagat Singh, only 23 at the time of his execution, was born into a Sikh family and became a self-educated socialist and an inspiring revolutionary. Communal hatred had already begun to divide the Indian masses and Bhagat Singh advocated class struggle as the antidote. His writings, a central motif in the film, were suppressed by the British and are still relatively unknown, but his courage became legendary.”

In a letter dated 16th April, 1990, Patwardhan wrote to this writer on “why the film (In Memory of Friends) had to be made in this particular way”. It is perhaps necessary to recount the director’s words in order to give readers (and viewers) an idea of the clarity of mind and apparent simplicity of style that characterized this film on arguably the most serious cancer afflicting the country today : Communalism. Whether it is Punjab, Kashmir or Ayodhya, people seem to be roused to incendiarism by the most primeval and reactionary of passions. Mass poverty, disease, illiteracy, unemployment, scarcity of water and roads – all disappear into a world of forgetfulness as shrieks of assertion in the name of organized religion claim headlines. Reams of pathetic justification by avataars in saffron or green or what have you leave the masses confused and bewildered. With a Rightist government in New Delhi and similar outfits in power in several State capitals, the fear is gaining ground that official encouragement to violence and terror in the name of religion will increase.

Patwardhan wrote : “Hamara Shahar (a film made in 1985 by Patwardhan on demolition drives by the municipal corporation against Bombay’s slum and pavement dwellers) was a relatively easier film for intellectuals and Leftists to appreciate – it showed the glaring injustices of our class-ridden society. But with In Memory of Friends, you have to really understand the need (all emphasis Patwardhan’s) for such a film. Let me briefly elaborate.

- Outside Punjab and for all non-Sikhs, it is important to fight the image of Sikhs as terrorists. Hence, the image of Sikhs fighting against terrorists as well as the State is a very welcome and positive image.

- The secular forces in our country are on the defensive. This viewpoint needs to be forcefully presented. And because they are numerically small, their heroism is greater, just as Bhagat Singh also represented a minority of the freedom struggle.

- Bhagat Singh’s words are remembered only by a small section of the Left; to the rest, he is merely a brave martyr. Secular forces need to revive their symbols if they are not to be drowned by the revivalism of fundamentalists.

- While pro-Khalistan terrorists and sympathizers need to be shown as incorrect and dangerous, they should not be dehumanized but their psyche has to be understood by understanding why they became what they are.

- The simple wisdom of ordinary people is often more telling than the theories of the activist.

- The need for Left and democratic unity (the CPI woman and her Naxalite son, and photographs of different martyrs at the end of the film) is shown.

- The whole film avoids voyeurism – no overt violence and blood; just ideas, fighting ideas. The blood is there in the background, not in the foreground.

- The red flag throughout the world now reminds people of Stalin and Ceausescu. But here we see it as the embodiment of reason and humanism and hope.

- Another important point. There are those in the Left – like CPI, CPI(M) – who make the mistake of fighting only Khalistani terrorism. Again, there are sections of the CPI(ML) who virtually support Khalistani terrorism or are silent about it because they feel anything anti-State is OK and because they treat Punjab as a ‘nationality’ question. Both are errors, because the Sikh identity and the nationality issue became popular only after Bluestar and Delhi massacre and State repression. Hence it is a reaction and not deeply rooted. Even today, if there were no fear of terrorist reprisals, the majority of Sikhs would very much consider themselves Indians. Anyway, how can the Marxists ever agree to unite with fundamentalists, whatever be their analysis. That is opportunism. So, the film should be useful to all confused Marxists. They may disagree with it, but at least it has made them think.”

Five years after the Punjab film, in 1995 Patwardhan and his associate, Simantini Dhuru, directed A Narmada Diary (60 minutes, colour). The film documents five years in the life of the Narmada Bachao Andolan which led an agitation against the building of the Sardar Sarovar Dam on the river Narmada. The film has now become a talking-point with the recent approval given to Gujarat by the Narmada Control Authority to raise the height of the dam from 121.92 metres to 138.68 metres. While Ahmedabad and New Delhi claim that raising the dam height by 17 metres will benefit parched parts of Gujarat, activists have been angered by what they see as a move dictated by government high-handedness and insensitivity to the plight of Adivasis and other ‘excluded’ sections of society. The activists argue that plain destruction is being inflicted on the victims in the name of development and progress. While the Chief Minister of Gujarat, Anandiben Patel expressed her “heartfelt gratitude” to Narendra Modi and tweeted that achchhe din aa gaye hain (good times have arrived), Medha Patkar, the Narmada Bachao Andolan leader and renowned social activist, has expressed her strong disapproval.

Patkar : “The decision taken is undemocratic as the government has not considered the fact that 2.5 lakh people are living in the area, which will submerge due to the raising of the height of the dam. The government has neither given us any hearing nor made any attempt to know the ground reality before deciding to go forward with the Sardar Sarovar Dam construction to its final height.”

Several films have been made on the threat that the dam posed to the life and property of lakhs of endangered Adivasi and Dalit families of the four States that come within the purview of the Narmada dam project, namely, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, but arguably none has captured the threat and agitation by activists to defeat it, as effectively as Patwardhan and Dhuru’s A Narmada Diary. In a style that is both highly visual and penetratingly interrogative, the filmmakers question the very ethics of large dams being built with foreign loans (in this case, from the World Bank) and benefitting the well-off sections of urban society. Even as the affected Adivasis speak of the dangers of un-settlement they face, the film portrays an entire way of life enveloping cultural and civilizational norms and values being washed away, with great compassion and a suppressed anger. The aesthetics of the film slowly grows out of the absence of ethics on the part of politicians and planners claiming to be working for the good of the people. The poetry of protest is expressed in a strikingly earthy idiom.

At the time A Narmada Diary was made some twenty years ago, Patwardhan had rightly pointed out that the gigantic ‘development’ project on the banks of the Narmada “has been criticized as being both uneconomical and unjust in that its main beneficiaries will be the well-to-do in urban centres and its sacrificial victims, the rural poor. When completed, the dam will have inundated 37,000 hectares of land, including fertile fields and forests, displaced over 200,000 people, and cost Rs.400 billion. Environmental, cultural and human costs, as is usual in such mega-projects, have never been fully estimated.”

Patwardhan went on to make a telling comment on what it was that made the bureaucracy and the political class almost without exception, take such a keen interest in ensuring the Sardar Sarovar Dam see the light (or more likely, the darkness) of day. “For nearly a decade the people of the Narmada Valley, a majority of them Adivasis, have resisted the dam. In the face of their unity, the World Bank had to withdraw its funding for the project. But Indian government officials, either induced by kickbacks that often accompany large projects or seduced by the now-discredited rhetoric of the ’50s when large dams (like the Hirakud in Orissa or the Bhakra-Nangal in Punjab) were considered to be ‘the temples of modern India’, have steadfastly refused to halt construction.”

Patwardhan was speaking of a more hopeful day when he observed that “in a situation where government resettlement and rehabilitation programmes have proved inadequate and inappropriate, the Narmada Bachao Andolan has emerged as one of the most dynamic struggles being fought in India today. With their insistence on non-violence and their determination to drown rather than shift out of their homes and land, the people of the Narmada Valley have become symbols of a global struggle against unjust and unsustainable development.”

Much water has flowed down the Narmada since those words were spoken, and the resistance once mooted by the villagers and their supporters from urban areas exists now more in spirit than in substance. The recent political change in New Delhi, which has given hitherto unimaginable power to the forces of corporatization and those of Hindutva humbug, now makes it extremely difficult for activism in any form to emerge from the ranks of the rural proletariat or the urban intelligentsia. The Modi juggernaut is sure to mow down with impunity anyone coming in the way to the realization of the promised ‘Ram Rajya’.

Yet, oppose one must; oppose crimes against humanity wherever they are being committed, using ‘national interest’ or ‘public good’ as an excuse; oppose with whatever resources that are available to the nay-sayer and the whistle-blower. One is reminded here of the saying : To forget the past is to forfeit the present and the future. One way not to forget the past is to re-visit Patwardhan’s socio-political manifestos relating to, among other subjects, the Emergency, the Khalistani insurgency, and the Narmada Bachao Andolan, seeking in each a subtle sign, a hidden signal, an unnoticed source of strength from where to begin the struggle once all over again.

More than two hundred years ago, someone said, Man was born free, but he is everywhere in chains. One daresay, those chains were forged not to be feared by those at the receiving end, but to be defied with whatever that can be coaxed out of the human imagination for a freer and fairer world.

( Vidyarthy Chatterjee writes on cinema,society, and politics.)

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER