“When I first got my periods, I felt I was about to die. I didn’t know what it was,”

Says Sonam, a resident of Nalhar village in Mewat district of Haryana, who is now in her 20s and married. Sonam’s experience is the story of every second girl in India. Menstruation as a subject is still a taboo in Indian society. Even in the 21st century where technology has advanced exponentially, a large part of our population feels awkward to have a conversation about periods. A large section of society continues to be ignorant forcing women to deal with this biological process in fear and shame. When it comes to awareness, even educated masses lack the language for civil conversation on the topic. One of the reasons behind this issue is the concept of pride and honor which we often attach to women in our society. If you ever wondered why the majority of the abusive phrases share a feminine origin, you have scratched the surface of the cultural aspect of this issue.

The above screenshot is from a short clip posted on Youtube by Scoopwhoop Unscripted as a part of the series – Street View. The host Samdish Bhatia questions male students from Delhi University on the topic of Menstruation.

Where some of the students seem confident in their answers, others tried to bridge the gap with what they could recall from their textbooks. The lack of awareness and inability to adopt a civil language to converse on the topic of menstruation is just the tip of the iceberg. Unhygienic menstrual conditions often result in chronic health problems in women. It is alarming to see how many times these illnesses are further aggravated due to their inability to seek medical help on time.

According to Water Aid, 66 per cent of the country’s female population begin menstruation totally unaware and unprepared. While at a global level, menstrual hygiene is recognised under Sustainable Development Goals, it continues to be a subject of gender disparity. In India, there are 355 million menstruating women, accounting for nearly 30 percent of the country’s population. School-aged girls in marginalised communities face the largest barriers to MHM, as many schools do not have the necessary facilities, supplies, knowledge, and understanding to appropriately support girls during menstruation. As per a survey, out of the 355 million menstruation women, 23 million drop out of school annually due to lack of menstrual hygiene management. Let’s take a deep dive into the current support systems for Menstrual Health Management (MHM) across schools in India.

Watering the roots – MHM in schools

Shruti wants to grow up and become a scientist. Math classes for one, always excite her, afterall she is a Math wizard. But today something is different. As the bell rings, all students return to the classroom. Shruti walks uncomfortably to her desk and quietly sits down. As the lecture ends, she remains seated like she is glued to her desk. The teacher notices her sitting awkwardly and asks her what’s wrong? She points at the blood-stained skirt. The school lacked separate toilets for girls and boys and the water supply was inconsistent. To this, the teacher asks her to go back home and ask her mother for help. Her friends laugh at her as she leaves the classroom. While walking back home, Shruti is confused about what happened to her in the school. She hopes her mother would have all the answers. She enters her home but before she could ask any questions, her mother notices the stains on her skirt and responds with disgust. That was the last day Shruti went to school! Her mother decided that Shruti should rather stay at home as going out when on periods would be an act of shame. After all, that’s what Shurti’s mother was always told.

As per the data in 2012, 40% of all government schools lacked a functioning common toilet, and another 40% lacked a separate toilet for girls. This negatively impacts their education and ability to stay in school. In Shruti’s case even though the teacher wanted to help her but lack of proper infrastructure forced her to send Shruti back home.

Providing functioning separate toilets, sanitary pads and soaps are essential but not enough. Shurti’s inability to go to the school was based on her mother’s decision. If her mother was aware that menstruation is not something to be ashamed of, she would have clarified her doubts and send her to school the next day. A 2014 report by the NGO Dasra titled ‘Spot On!’ found that 70 percent of mothers with menstruating daughters considered menstruation as dirty Hence, we need an approach towards spreading awareness in schools that is also inclusive of the community around it.

If Shruti’s classmates were aware of MHM practices, they would have been more supportive of her. But most girls do not consistently have access to education on menstruation and puberty in part because it is not mandated by the Government. The same report highlights the fact that 71 per cent adolescent girls remained unaware of menstruation till menarche. Even when schools do have programs, teachers find the topic embarrassing to discuss in a classroom, they are rarely trained, and consequently, they rarely teach it. In both in-school and out-of-school programming, the curriculum focuses more on the practical aspects of managing menstruation (e.g., product use), rarely includes biological aspects, and ignores psycho-social changes.

Current MHM curriculum misses out on providing sustained mentorship for girls to cope with changes. Facilitator quality for in-school and out-of-school programming also remains weak. Like Shruti’s, most adolescent girls in India rely heavily on their female influencers, particularly mothers for information on menstruation. However, mothers do not know or feel comfortable discussing menstruation, their advice is often limited to period management and tends to reinforce negative beliefs. Social norms and community attitudes associated with menstruation also inhibit women and girls from using toilets and disposal mechanisms appropriately. For example, 91% of girls in communities in Gujarat report staying away from flowing water during menstruation. In the past years, the government has launched two main schemes aimed at generating awareness in schools and communities. It is important to understand how much of the ground these programmes are able to cover before plugging the gaps.

Promoting health and hygiene awareness

The Union government launched the Rajiv Gandhi Scheme for Empowerment of Adolescent Girls (SABLA) across 2015 districts in the country. The scheme aimed at improving health conditions for adolescent girls with menstrual hygiene as an important component. But it faces issues as there is less coverage of aspects of reproductive health, irregular educational sessions for adolescent girls and irregular visit of experts for providing health and nutrition education.

Leverage the use of sanitary pads

The Union government launched the Rashtriya Kishor Swashthya Karyakram (RKSK), aimed at improving the health and hygiene of an estimated 243 million adolescents. Menstrual hygiene was also included as an integral part of the programme. RKSK prioritizes the provision of sanitary pads and the provision of sustained support and information on menstruation through counsellors. However, information is often limited to instructions on product use.

MHM Guidelines mention the need for convergence across departments to improve MHM. However, the guidelines lack clarity on what convergence might look like in action, i.e., who specifically will coordinate or oversee the coordination across departments and levels. For example, RKSK and SABLA both prioritize creating awareness about MHM among adolescent girls; however, there is limited clarity on how a counsellor under RKSK’s Adolescent Friendly Health Clinics and an Anganwadi worker supported by SABLA may complement each other’s efforts.

Both these government programs face a lack of human resources. Although MHM programs leverage health workers (e.g., ASHAs, counsellors) and teachers to provide MHM education, their comfort in discussing sensitive topics, particularly when talking to boys, varies and the quality of their training programs is inconsistent. Targeting teachers and Community Health Workers presents an opportunity for sustainably scaling access to education and awareness on menstrual health, particularly through national programs (e.g., RKSK). MHM curricula already exist as well. We need to build facilitator capabilities to provide education and psycho-social support at scale. A good example of efforts towards this direction of providing psycho-social support is Menstrupedia. As a for-profit enterprise, Menstrupedia has designed and developed a comic book on menstruation adapted to the local context to provide awareness and education on MHM to adolescent girls. Programming that educates mothers is rare. There is a need for evidence-based programming on enabling mothers to provide accurate information on MHM and appropriate ongoing support at scale. Uteri in Kerala Unite (UKU) by The Red Cycle stands out as an example for helping locals reach accurate information in MHM practices. UKU is a campaign that we conceptualised in order to tackle these problems from a grassroots level; more specifically from schools. The Red Cycle as an organisation is creating the much-needed impact in MHM space by building safe spaces for conversations around menstrual health, starting from the classrooms where these individuals are in, with their mentors and peers.

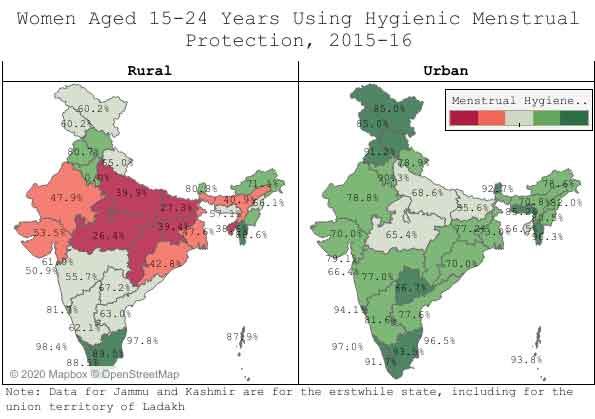

The figure above points out the higher scope for the improvement of MHM practices in rural areas as compared to their urban parts.

WASH United India is working in the sanitation space to create awareness. It has piloted as Game-based MHM Curriculum in a few states to empower girls to overcome the stigma around menstruation. The game also engages boys as supporters and teachers so that they can be available for sustained guidance. It also initiated Menstrual Hygiene Day (28th May) Advocacy effort to elevate the issue of MHM within the development sector. The Great WASH Yatra (Nirmal Bharat Yatra) a mobile carnival coordinated by Wash United India engaged over 16,000 people in schools and communities across 5 Indian states on sanitation.

The real change starts with you

To spread awareness in schools we need to make the school curriculum inclusive of biological and psycho-social aspects of menstruation. For this the curriculum needs to be friendly such as a game based approach which also includes boys. Teachers on the other hand need to be properly trained to resist the urge of skipping the topic and rather act as supporters in the process. At a community level, we need evidence based programming, with mothers playing the role of mentors. To initiate this, we need to set up programs that are built with the locals and accurate information is available at ease. On a policy level, to improve operational clarity, the government can assign MHM specific performance indicators to various Ministries and identify an MHM Champion across Ministries.

Shurti had immense potential in her, but due to lack of awareness and right mentorship she had to drop out of school. If these changes were in place, Shruti would have been able to achieve her dream of becoming a scientist. Her contributions to science would have led to life changing innovations around us. The reality is that Shurti’s story is still shared by 23 million girls every year. In addition to millions of brilliant scientists, teachers, doctors, engineers, leaders etc we are also losing an important part of humanity.

But the glass is half full if we make the right choice as early as possible. At an individual level we all can to work to break the stigma attached to menstruation. As you must have heard it before, the real change starts with you, all it takes is a choice to be consistent. Take up any aspect of menstrual hygiene discussed and dig deeper. If it seems too daring, start small by talking to your mother/sister/wife etc about their experience with periods. Let’s put our two cents to save a bright future.

Menstrual Hygiene – Making Hygiene Affordable

In a remote village of Bihar, lives Kamla (28) with her two sons. Lately, she’s been experiencing extreme pain while urinating. As her sons take her to the nearest city hospital the doctor examines her. She is diagnosed with a chronic urinary tract infection. Doctor inquires about her menstrual hygiene and gets to know that Kamla has always used the same two pieces of cloth to manage her menstrual flow. When asked the reasons behind doing so, Kamla says she couldn’t afford to buy the commercial pads.

Kamla’s story resonates with the 70% of women in India who say their family cannot afford to buy sanitary pads. In fact in rural areas, only 2 to 3 per cent women in rural India are estimated to use sanitary napkins as per 2016 data. This results in women resorting to unhygienic practices during their menstrual cycle, such as filling up old socks with sand and tying them around waists to absorb menstrual blood, or taking up old pieces of cloth and using them to absorb blood. Such methods increase chances of infection and hinder the day-to-day task of a woman on her period.

Pads made by premium commercial manufacturers are up to 1.5 times more expensive than pads made by low-cost manufacturers. When it comes to alternatives to the commercial pads we are presented with reusable pads and insertable products as two of the most popular options. Both these face their own set of problems when it comes to being accepted by the users, especially in rural areas. For reusable pads, the main issue is low demand and market share. This is due to the upfront cost, lack of awareness about the product and product use and limited aspirational value. On the other hand, insertable products such as tampons and menstrual cups are considered as a high barrier product in India given apprehension among women with inserting products as well as the community’s perception that usage of tampons affects a woman’s virginity. Due to this reason leading stakeholders in MHM space including the national government do not advocate insertable products as an option for women and girls. In the past years, the government has launched two main programs to solve this issue. Let’s take a stock check on how much progress they’ve made.

Distribution of Pads – Couple affordability with accessibility

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare launched the Freeday Pad Scheme, a pilot project to provide sanitary napkins at subsidised rates for rural girls. As per the scheme the sanitary napkins branded as Freedays are sold at Rs 6 per pack of six napkins by Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs). As the supply was irregular and inadequate, financial problems emerged as the main hurdle for using Freedays. ASHA retains Re1 per pack as an incentive and gets a free pack of Freedays every month. The balance Rs5 is to be deposited in the state/district treasury. ASHAs involved in napkin distribution are not satisfied with the supply and subsidy were given to them. Also, the villagers are ignorant about the disposal of Freedays without any dustbins for the product. The scheme has ignored the opportunity cost involved. On March 8, 2018, also known as International Women’s Day, the government launched 100% oxy-biodegradable sanitary napkins “Suvidha” in packs of four priced at 2.5 rupees/napkin to be available at Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana Stores. In 2019, the price of Suvidha napkins was reduced to 1 rupee/napkin. This scheme faces blockers when it comes to implementation. There is a scarcity of Suvidha napkins at the Janaushadhi Kendras. At the point of distribution, there is a lag between orders and delivery. Other blockers come in terms of awareness as few people are aware of this scheme. Despite government initiatives to provide low-cost disposable sanitary pads, in the form of Free Days and Suvidha, requirements for safe MHM products far outweigh their availability or accessibility. Hence to solve the problem of affordability we need to couple it with accessibility.

To improve the accessibility of sanitary pads, we need decentralised models of production of low-cost sanitary pads by community-based organisations/self-help groups. An example of such a model can be seen in Auroville of Tamil Nadu, where EcoFemme is manufacturing pads, providing livelihoods to local women, educating in-school girls on product use, and providing the pads free of cost. A single cloth washable pad (that lasts 75 washes) is equivalent to 75 single use and throw disposable sanitary napkins. Cloth pads prevent significant amounts of waste. Made from natural materials, they are healthier when cared for properly and they save money as well. Another example of the Not Just a Piece of Cloth Program by Goonj. Goonj produces simple, reusable cloth pads made by local women using old cloth; cloth pads are seen as a tool for women’s empowerment.

Market-Based interventions including technological innovations to increase the capacity of low-cost machines are needed to increase scale, capacity, and quality of pads produced as part of the decentralized model. For example, Jayashree Industries is one of the early inventors of a low-cost disposable sanitary pad, the manufacturing machine in India. Today, these machines are sold to SHGs and NGOs across 27 states in India. This social enterprise has inspired several other innovators (e.g., Aakar Innovations) There is a need to further explore the reasons for the limited success of SHGs and explore other holistic interventions to provide access to preferred products at scale.

Localise the production and incentives the distributors

Hence, affordability is an important piece of improving the reach of sanitary pads in the country but it’s incomplete without a distribution network that is kept in check. One way to ensure distribution is to make sure the components of the distribution are satisfied with the incentives. For example, in the case of the Freeday pad scheme, if ASHA workers were provided with enough incentives and the satisfaction level was monitored, it would have been a more successful initiative.

If Kamla had access to affordable sanitary pads, she would not have resorted to using two pieces of cloth all her life and consequently would not be suffering from a chronic illness. Every year millions of women share Kamla’s story. The best way forward is to enable low cost manufacturing of pads with the help of locals and create decentralised models. State governments should partner with local enterprises and run needs assessment to map the requirements of sanitary products. This will create a perfect competition in the market and equip the users with accessibility.

Menstrual Hygiene – Future Ready Waste Disposal Process

About 336 million girls and women experience menstruation in India, out of which approximately 121 million use disposable sanitary napkins. If we roughly take the number of sanitary pads used per menstrual cycle as eight, over 12.3 billion disposable sanitary pads are generated every year. The disposal of such plastic pads have become a huge concern. Every disposable pad or tampon you have used in your lifetime, without exception, is contributing to either soil, air or water contamination.

Women, both rural and urban, face the question of disposing the pads every month, while government authorities struggle to find a way to handle the staggering amount of sanitary waste generated every month. While some women wrap it in plastic or paper and throw it along with domestic garbage, some flush them down or throw them into water bodies. Vivian Hoffmann of the University of Maryland in her research in Bihar found that 60% of women disposed of their sanitary waste in the open and often in an open defecation ground.

What makes disposal and collection of sanitary pads such a complex problem?

“Almost 90 percent of a sanitary napkin is plastic” says Swati, a Senior Research Associate at the Centre for Science and Environment.. The thin top layer on napkins, known as the dri-weave top sheet, is made of polypropylene (a plastic polymer). The padding is mostly wood pulp mixed with super absorbent polymers and the leak-proof layer is made from an impermeable polyethylene, according to Ecofemme, a social enterprise working on Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM). Most of the chemicals from these pads reaching the soil causes groundwater pollution, loss of soil fertility. Considering the fact that 66% of Indian population is rural which heavily depends on groundwater for all purposes, polluted groundwater is making the country prone to a number of health hazards. Whereas losing soil fertility causes a sharp decline in agricultural capacity, it also alters how water flows through the landscape, potentially making flooding more common. From a waste management standpoint typically one such sanitary pad takes 500-800 years to decompose. Keep in mind we are discussing about 12.3 billion sanitary pads per year.

In Uttar Pradesh’s Gorakhpur city, Rashmi (32) who lives in a slum nearby collects this waste and segregates it to make 100-200 rupees daily. Rashmi also has two kids who help her out often by skipping school. She says her most uncomfortable and time taking part of her job is to segregation sanitary pads which are often tightly packed in polythene bags. Today, Rashmi suffers from multiple health hazards including tetanus and AIDS.

Rashmi’s story is shared by millions of waste collectors in the country. None of them wish their story to be repeated by their children. After you hand the soiled napkins over to the garbage collector, the napkins are collected as household waste by garbage collectors and later segregated, often manually. After this, the sanitary waste is driven out of the city and buried in a landfill on the outskirts of a city. At times they are shredded before being buried. Waste pickers separate out soiled napkins from recyclable items by hand, exposing themselves to micro-organisms like E.Coli, salmonella, staphylococcus, HIV and pathogens that cause hepatitis and tetanus.

What do the laws say and what have we done so far?

According to the Solid Waste Management (SWM) Rules, 2016, every waste generator must segregate waste into three fractions — wet, dry and domestic hazardous waste. Every household needs to ensure that sanitary waste should be properly wrapped. The rules say that sanitary waste should be kept in the dry waste bin and should be handed over separately. The rules also mandate the manufacturers or brand-owners of sanitary pads to work with local authorities on providing necessary financial assistance to set up waste management systems for sanitary waste. Also, they need to ensure that they set up collection systems to take back the packaging waste of their products, educate as well as create awareness on proper disposal of such pads. However, nothing of this sort has happened on the ground. Indian government’s interim solution to the problem is ‘incineration’. While WHO says that incineration of sanitary waste should be done at temperatures above 800 degrees, in India, not only is it difficult to handle such high temperature, there is no provision for monitoring the emissions from the incinerator.

Given infrastructure for waste disposal is a multi-billion policy issue, what can we do in the interim?

‘Green the Red’, a pan-India campaign to spread awareness on Sustainable Menstruation options, led solely by volunteers, started a petition asking for tax cuts only for reusable menstrual products. The petition details the dangers of flooding the Indian market with disposables and educates the reader about the benefits of reusable options. One such option is a menstrual cup. Although menstrual cups have a high upfront cost – ₹300-1000 INR compared to ₹30-60 for disposable sanitary products such as pads – they last for 10 years and after two years become the more cost effective option. From a marketing point of view, these are well received by married women across the country, especially in the urban areas, but yet to gain large-scale acceptance in the market. Menstrual cups also require very little water to keep it clean which is an added advantage, especially in areas where there is a shortage of clean water, to begin with.

The leading Indian brand in menstrual cups is StoneSoup cups.These cups are available in a range of firmness – from soft to hard – making them suitable for various body types, levels of physical activity and flow. They’re safer for women’s reproductive health than plastic pads whose chemical fragrances and absorbents have been linked to allergies, irritations and discomfort. One cup can be used upto 10 years. Another such menstrual cup brand is Shecup. Here’s a comparison chart that can help you choose the most suitable option for yourself.

When it comes to rural areas, due to the lack of waste segregation practices, incineration is a better alternative. A good option low-cost manual incinerators or electric incinerators can be used for this purpose. As we explore innovative business models in the upstream part of the value chain, we have solutions such as SanEco which is a waste management system that works on a chemical and mechanical disintegration method. The end product of this process is cellulose, and plastic pellets. The creators of SanEco claim that this cellulose can be used to make paper and the plastic pellets can be used to manufacture packaging material or construction material. The blood and other body fluids are also broken down in the same process and removed through a separate outlet as sewage. When tested the bacterial load for this sewage is found to be within the limits prescribed by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). So this liquid can be directed into regular sewer lines.

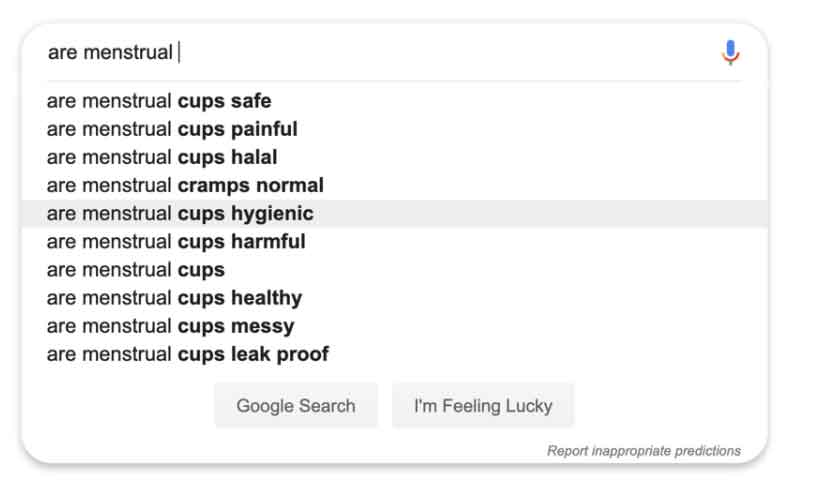

The above picture is a snapshot of google search in India regarding menstrual cups. Notice the ranking and variety of preferred questions. A woman spends approximately 2,100 days menstruating, that’s almost six years of her life. Educating the public about menstruation, seeking to end taboos around the topic and providing infrastructure for maintaining hygiene will go a long way in improving the conditions of those in need. The Red Dot campaign in Pune is a successful step in this direction. The city-wide project was launched in two parts, one to raise awareness on ways to dispose of sanitary waste and the other, to make sanitary napkin manufacturers more accountable. Seven months into the campaign, a sample of 75 trained SWaCH leaders (serving 15,000 households daily) reported that 50% of their customers were wrapping and marking their sanitary waste, compared with 0% before the campaign began.

In 1989, when Procter & Gamble launched sanitary napkin brand Whisper in India, the brand was refused the prime time advertising spots. The reason given by the channels was that its commercial used the word ‘period’ in voice over and showed the sanitary pad. They had to take special permissions to advertise their brand. In the past two decades we have come a long way in our battle against social taboos around menstruation. The Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation has recently issued Menstrual Hygiene Management Guidelines for schools and households. These address specific sanitation and hygiene requirements of adolescent girls and women. Apart from separate toilets and safe menstrual waste mechanisms for girls, the guidelines also call for the sensitisation of men, boys, communities and families about menstruation. Technological advancements are leading to rapid innovations and social media has made it easier for people to voice their thoughts. As we move into the future we must learn from our mistakes in the past and recognise the significance of our individual role along the way.

Execution of plans is as important as planning them. Let’s have a look at the feasible priorities in upcoming decades for a sustainable execution policy in MHM space.

The central government shall focus on creating more accountable schemes. A central repository of data for all programs and policies will go a long way when it comes to measuring impact of programs. State governments shall focus more on framing relevant state policies for MHM programs and use data driven frameworks to make decisions on the budget allocations. At the district level, officer training shall be monitored and more initiatives to be added for youth to get involved. At block level, extensive surveying shall be done to map the sub issues and causes. At community level, leadership shall be encouraged for those who are willing to take the first step. For example, the newly launched School Health Programme under Ayushman Bharat enables teachers to act as health ambassadors to inform students about health and disease prevention through interesting activities. NGOs and corporations shall be encouraged to partner with multiple stakeholders across levels of governance and showcase their impact again using data driven frameworks. Vertical leadership shall be encouraged for existing programs.

Solving MHM problems is a pressing issue in today’s social sector. As educated citizens I’m hopeful that some of us will choose to play a direct role first by educating themselves and those around us.

List of References

- http://www.nrhmhp.gov.in/sites/default/files/files/MHP-operational-guidelines.pdf

- https://swachhindia.ndtv.com/odisha-bhubaneswar-dharmendra-pradhan-launches-ujjwala-sanitary-napkin-scheme-menstrual-hygiene-29341/

- https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/health/mapped-menstrual-hygiene-across-the-states-in-india/article24016449.ece#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20National%20Family,be%20hygienic%20methods%20of%20protection.

- https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/health/menstrual-hygiene-management-in-india-still-a-long-way-to-go-63606

- http://www.ijph.in/article.asp?issn=0019-557X;year=2018;volume=62;issue=2;spage=71;epage=74;aulast=Sinha

- https://www.nhp.gov.in/menstrual-hygiene-day_pg

- https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/Menstrual%20Hygiene%20Management_FINAL.pdf

- https://www.savethechildren.org/content/dam/global/reports/health-and-nutrition/mens-hyg-mgmt-guide.pdf

- https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=menstrual-cycle-an-overview-85-P00553

- https://www.unicef.org/wash/files/UNICEF-Guide-menstrual-hygiene-materials-2019.pdf

- https://swachhindia.ndtv.com/23-million-women-drop-out-of-school-every-year-when-they-start-menstruating-in-india-17838/

- https://path.azureedge.net/media/documents/ID_mhm_mens_prod_india.pdf

- https://menstrualhygieneday.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/FSG-Menstrual-Health-Landscape_India.pdf

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52718434

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/ashoka/2015/06/10/5-amazing-companies-working-in-menstrual-hygiene/#45a0746c59bf

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0166122

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/sanitary-napkins-may-be-free-but-schoolgirls-suffer/articleshow/65679979.cms

- https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2016/12/28/506472549/does-handing-out-sanitary-pads-really-get-girls-to-stay-in-school

- http://www.ccras.nic.in/sites/default/files/Notices/16042018_Menstrual_Hygiene_Management.pdf

- https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/Menstrual%20Hygiene%20Management_FINAL.pdf

- https://menstrualhygieneday.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/MHD_infographic_MHM-SDGs.pdf

- https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/1-SABLAscheme_0.pdf

- https://www.livemint.com/Politics/zbk4JLAnsoHjmbvp1rgeNJ/Use-of-sanitary-pads-sparse-despite-govt-schemes-studies.html

- https://theprint.in/india/one-rupee-sanitary-pads-welcome-but-govts-janaushadhi-stores-often-dont-have-them/283474/

- https://www.ijcmas.com/8-3-2019/Divya%20Rajpurohit,%20et%20al.pdf

- https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2017PGY_UDAYA-RKSKPolicyBriefUP.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CmHo5mAfF64&t=162s

- https://edition.cnn.com/2018/07/22/health/india-tampon-tax-intl/index.html#:~:text=New%20Delhi%20(CNN)%20Sanitary%20pads,for%20more%20than%20a%20year.

- https://www.dasra.org/assets/uploads/resources/Spot%20On%20-%20Improving%20Menstrual%20Management%20in%20India.pdf

- https://swachhindia.ndtv.com/non-compostable-sanitary-waste-huge-threat-health-environment-experts-8349/

Rudresh Dahiya is an upcoming SBI Youth For India fellow who is currently working as an analyst in the development sector.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER