A 2014 report by the NGO Dasra titled Spot On! found that nearly 23 million girls drop out of school every year as they have to face lack of proper menstrual hygiene management facilities, which include availability of sanitary napkins and logical awareness of menstruation. “I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved,” said Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar. Inspired by this vision, Rushikesh Khandale, a young anti-caste thinker, activist and journalist from Aurangabad, Maharashtra decided to choose to work on menstrual stigma – a notional sense of disgust that modern India refuses to part with. “If 23 million girls are dropping out of our schooling system every year because of a natural process that their body undergoes, this is tragic and needs to change,” says Rushikesh.

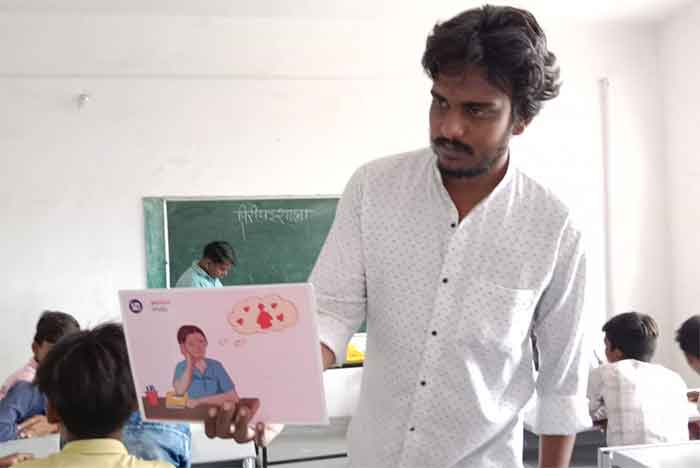

Rushikesh, a resident of Aurangabad, got selected for the prestigious Period Fellowship in 2021, and worked for fifteen months in a predominantly tribal district in Jhabua, Madhya Pradesh. The fellowship is offered by Uninhibited, a Bangalore-based NGO, working on making menstruation a non-issue in five states of India. Men working on abolishing menstrual stigma is a rare sight, and Rushikesh is challenging this rarity. For fifteen months, along with delivering social and behavioural change programmes with young men and girls in villages and communities, Rushikesh dug deep into understanding the social, political and economic complexities that shape how menstrual stigma operates in India. Here, he shares his learnings with us.

“What men often don’t realise is that menstruation is their issue too,” shares Rushikesh. In a world where men co-exist with women in families, intimate relationships, workplaces, communities and public and private spaces, men cannot but be bereft of the demands of a menstruating body. “I’m here because my mother could menstruate. Hence, menstruation is as much a reality around men as it is for women – since we grow up in a culture of silence that surrounds periods, men are not only unaware of the intense experiences the menstruators in their lives go through every month, they also choose to remain ignorant because of the priviliges that gender as a structure offers them. If we were to add all the days a menstruator bleeds throughout their lifetime one realizes that the total adds up to almost 7 years – that’s a significant number.”

“I remember, all my childhood, my mother used to hand me a bag without a word and only with a note for the pharmacist. The pharmacist would read the note, drop a wrapped package in the bag and I would go home. This entire exchange happened without a word, in total silence. It

was only when I grew up that I realised that the package was sanitary napkins for my mother and sisters.” Not to look to far away, Rushikesh realized that work around challenging attitudes and behaviours around menstruation can start at home. “For my first assignment, I sat with my family to talk about what periods are – to hear my elder sisters, father and mother talk about menstruation together was the first step for me.”

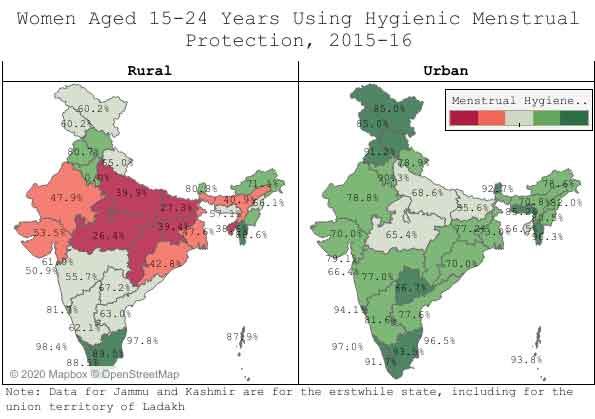

According to Rushikesh, issues that surround menstruation are not simply limited to health and hygiene, but they’re also an intergral part of realizing one’s fundamental and human rights. “The menstrual experience in India, is very much shaped by the structures of caste, class and gender. Take for example the fact that schools which struggle most with sanitary infrastructure in India are often public schools, whose students are almost always girls from poor families. Unaffordable menstrual products curtail access for poor families. Or the fact that caste is an omnipresent reality in everyday interactions in India – and menstrual stigma too is shaped by it. Fundamentally, menstrual stigma is born out of the notions of purity and impurity that are building blocks of caste. Once a girl hits puberty, her sexuality and desires are policed by the society to ensure she doesn’t marry below her caste or outside her religion. Child marriage, another form of discrimination and violence against women is also a product of this policing.”

Menstrual stigma is not the same for all kinds of men either. As the anti-caste thinker Kancha Illiah says, “Patriarchy is a far greater problem in so-called upper caste, upper class homes. Let me elaborate – while talking with my upper caste friends, who belong to rich families, they’re often understanding when I tell them about the issue. However, they find it hard to push these boundaries for their partners at home. When I was working in Madhya Pradesh with tribal men, the men were more receptive to changing attitudes and behaviours around menstruation once they became aware of how misinformed our understanding of menstruation is. In a basti, whenever a women experiences domestic violence, she often hits the man back and makes a ruckus about it. This is perhaps not always the case in flats and apartments.”

For Rushikesh, working with men to drive out menstrual stigma is as urgent as working with women. Men are often decision-makers in households – women have to consult them even for buying sanitary napkins. Most often, women don’t even dry their washed menstrual cloth with other clothes in the open sun fearing shame and stigma from the men in their households, risking vaginal rashes and infections. Rushikesh is continuing to fight against menstrual stigma even after the end of his fellowship by working on creating and implementing programmes to end the discriminatory practices around menstruation in rural Marathwada. Rushikesh shares, “For me, I would like to create a world where every man can create a space full of trust and safety for menstruators in their lives to share their troubles. It is only when men are made aware of both the issue and their own privileged role in it, will they start thinking about menstruation. Healthy conversations around such an intimate issue perhaps is a starting point to make menstrual stigma truly a thing of the past.”

The writer is a development worker from Maharashtra. Share your feedback on [email protected]

Charkha Features