The other day I came across a copy of an old newspaper – The Statesman (Kolkata edition) of August 4th 1994. As I browsed through the headlines for a glimpse of the world twenty six years back, the heading “Looting in Yemen continues after end of war” caught my attention, given I’ve seen headlines about Yemen being bombed etc., currently. What war was that and what war is this? What I have below is essentially my exploration into this country’s troubled times, as an outsider and sympathiser of a civilization held captive, not by time, but by unchanging circumstances. I have quoted from the 1994 article interspersed with what history records and hence there’s a curious interplay of micro elements and macro events – an interesting magnification at particles in a grand statue, a sudden arresting of the flow of time allowing zooming in at the grains of truths, leading to facts viewed through an emotional paradigm.

The war in Yemen, as with most other wars in history, was fought as much with weapons – Scud missiles, tanks, heavy artillery, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and even small range surface-to-surface missiles (SSMs) – as with political intrigues, conspiracies and megalomania. In a still continuing saga, it is a story about kleptocracy bringing the Arabian peninsula to its knees (Yemen is a country at the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula in Western Asia). But then again all history is as coloured and complex as the people writing them and the people recording them, and add to that the variety of conflicts and interests of the ruler and the ruled, the political and religious stakes of its neighbours, the economic and social ramifications of the world players and organizations – the result is quite an intricately layered matryoshka doll-like geopolitics – hard to decipher from the surface, harder still from inside.

And then what happens when such a country is hit by a pandemic? Does the cornerstone of a political identity, revolving around the frowns and moods of its mighty neighbours and world organizations, pay heed to the wrath of nature? Does the pressing need for survival yield space to sanity and humanity, humble the arrogance of destruction and satiate the endless caverns of nepotism and despotism?

Below I begin with an excerpt from the 1994 article that got me rolling into this turbulent historical ride through the peninsula, ending within the perils of the pandemic.

———————————

The Statesman 1994:

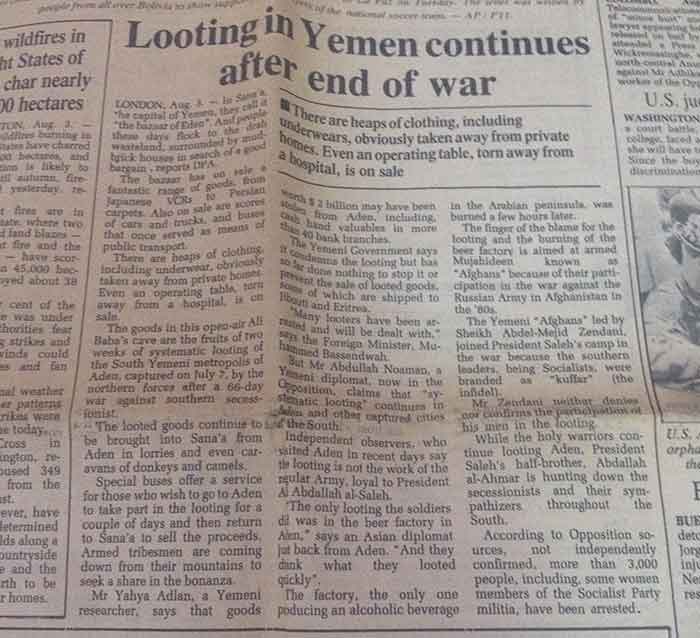

Looting in Yemen continues after end of war

London August 3: In Sana’a, the capital of Yemen, they call it “the bazaar of Eden.” And people these days flock to the drab wasteland, surrounded by mud-brick houses in search of a good bargain, reports DPA.

The bazaar has on sale a fantastic range of goods, from Japanese VCRs to Persian carpets. Also on sale are scores of cars and trucks, and buses that once served as means of public transport.

There are heaps of clothing, including underwear, obviously taken away from private homes. Even an operating table, torn away from a hospital, is on sale.

The goods in this open-air Ali Baba’s cave are the fruits of two weeks of systematic looting of the South Yemeni metropolis of Aden, captured on July 7, by the northern forces after a 66-day war against southern secessionist.

———————————

Civil War in the Arabian Peninsula:

The war (and the looting thereafter) that these lines refer to, is the first Yemeni civil war (1994). It was, roughly speaking, fought between north Yemen (who stood for united Yemen) and south Yemen (which wanted a separate state). The war resulted in the defeat of the southern armed forces, the reunification of Yemen, and the flight into exile of many Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP) leaders (those espousing a separate state) and other separatists of the South.

There had been other wars preceding it, but not going back too much, around the 1980s, reconciliation and unification began in the earnest. The Republic of Yemen (ROY) was declared on 22 May 1990 with Ali Abdullah Saleh (Saleh was the president of the then North Yemen) becoming President, and Ali Salem al Beidh, Vice President (Beidh was the former president of South Yemen).

However the first parliamentary elections, held on April 27, 1993, confirmed the fears of the southerners – former President of South Yemen, Beidh’s party (YSP) won only 54 of the 301 parliament seats, while former president of Northern Yemen, Saleh’s GPC (General People’s Congress) took 122 seats (and a northern Islamist-tribal alliance, Al-Islah, captured 62 seats). An uncomfortable and uneven three-way partnership was forged and hoped to be sustained.

Beidh withdrew to Aden in August 1993 and said he would not return to the government until his grievances were addressed. These included northern violence against his Yemeni Socialist Party, as well as the economic marginalization of the south. Negotiations to end the political deadlock dragged on into 1994 during which, both the northern and southern armies, that had never merged and integrated in the first place, fortified their presence at their respective frontiers. The bomb was all set to explode and waited for the spark that came in April.

On 27 April 1994, a battle formally erupted in Amran, near San’a. Both the north and the south blamed each other of starting it. On 4 May, the southern air force bombed San’a while the northern air force retorted by bombing Aden. President Saleh declared a 30-day state of emergency, and foreign nationals began evacuating the country. Vice President Beidh was officially dismissed.

The South announced secession and declared the Democratic Republic of Yemen (DRY) on 21 May 1994 but no international government recognized the DRY. In mid-May, northern forces began moving towards Aden. The key city of Ataq, which allowed access to the country’s oil fields, was seized on May 24. Aden was captured on 7 July 1994. Most resistance quickly collapsed and top southern military and political leaders fled into exile.

Exactly about twenty-six years ago, Yemen had been in almost an identical situation as she seems to be in now!

————————————

The looted goods continue to be brought in Sana’a from Aden in lorries and even caravans of donkeys and camels.

Special buses offer a service for those who wish to go to Aden to take part in the looting for a couple of days and then return to Sana’a to sell the proceeds. Armed tribesman are coming down from their mountains to seek a share in the bonanza.

Mr Yahya Adlan, an Yemeni researcher, says that goods worth $2 billion may have been stolen from Aden, including cash hand valuables in more than 40 bank branches.

————————————

President Saleh took control over all of Yemen. He was elected by Parliament on 1 October 1994 to a 5-year term. However, he remained in office until 2012, till he was toppled by popular unrest in the wake of the Arab Spring protests.

————————————

The Yemeni Government says it condemns the looting but has so far done nothing to stop it or prevent the sale of looted goods, some of which are shipped to Jibouti and Eritrea.

“Many looters have been arrested and will be dealt with,” says Foreign Minister, Muhammed Bassendwah.

But Mr Abdullah Noaman, a Yemeni diplomat, now in the opposition claims that “systematic looting” continues in Aden and other captured cities of the South.

…

While the holy warriors continue looting Aden, President Saleh’s half-brother, Abdullah al-Ahmar is hunting down the secessionists and their sympathisers throughout the South.

According to Opposition sources, not independently confirmed, more than 3,000 people, including some women members of the Socialist Party militia, have been arrested.

—————————————

“Dancing on the heads of snakes”:

Ali Abdullah Saleh (21 March 1947 – 4 December 2017) once said that governing the Arabian Peninsula country was akin to “dancing on the heads of snakes”, and dance, he did, for thirty-six years, with the shrewdest Machiavellian manoeuvring, but bringing neither glory nor fame, neither peace nor progress, in what Victoria Clark calls the “dark horse” of the Middle-east. And Fate seemed to have conspired to bring the Dark Horse to its knees.

He served as the first President of unified Yemen, from Yemeni unification on 22 May 1990 to his resignation on 25 February 2012, following the Yemeni Revolution (of the Arab Spring). Previously, he had served as the President of North Yemen, from July 1978 to 22 May 1990 (after the assassination of President Ahmad al-Ghashmi). So more or less from 1978 – 2012, that is for thirty six years, he was at the helm of affairs of Yemen, dancing on heads of snakes.

2011 Arab Spring: Exit Saleh, Enter Hadi

The 2011 Yemeni revolution (in the wake of the Arab Spring, which spread across North Africa and the Middle East (including Yemen) mass protests were initially against unemployment, economic conditions, and corruption, as well as against the government’s proposals to modify the constitution of Yemen so that Saleh’s son could inherit the presidency.

In March 2011, police snipers opened fire on a pro-democracy camp in Sana’a, killing more than 50 people. In May, dozens were killed in clashes between troops and tribal fighters in Sana’a and by this time, Saleh began to lose international support. His kleptocratic presidency was becoming more and more untenable and on 23 November 2011, Saleh flew to Riyadh, in neighbouring Saudi Arabia, to sign the Gulf Co-operation Council plan for political transition, which he had previously spurned. By signing, he agreed to legally transfer the office and powers of the presidency to his deputy, Vice President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi.

Hence, eventually Saleh was ousted as President in 2012 and was succeeded by Hadi, who had been his Vice-President since 1994.

Exit Hadi, Enter Houthis:

Hadi took office for a two-year term upon winning the uncontested presidential elections in February 2012. However Saleh returned in February 2012 and in spite of severe protests by the common man, parliament granted him full immunity from prosecution. (Saleh’s son, General Ahmed Ali Abdullah Saleh, continues to exercise a strong hold on sections of the military and security forces.)

In May 2015, Saleh openly allied with the Houthis (the Houthis belong to the Zaydi sect of Shias, which comprise nearly 40 per cent of the Yemeni population) in which they succeeded in capturing Yemen’s capital, Sana’a. The Houthi takeover in Yemen, also known as the September 21 Revolution (by supporters), or 2014–15 coup d’état (by opponents), was a gradual armed takeover in which Saleh, the Houthis and their supporters, seized power from the Yemeni government, forcing incumbent President Hadi to resign and flee the country to Saudi Arabia.

Oil , IMF, and Coup d’état:

The seeds of unrest and discontent had been sown quite sometimes back though, much of which can be attributed to imposition of IMF-induced policies and resultant corruption.

On July 30, 2014, the Yemeni government lifted subsidies on fuel prices, after pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which conditioned its continued financial assistance on these reforms.

The government raised the price of regular gasoline to 200 Yemeni riyals per liter (93 US cents) from 125 riyals (58 US cents). The price of diesel used for public transport and trucks rose to 195 riyals per liter (91 US cents) from 100 riyals (46 US cents).

Yemen had among the highest level of energy subsidies in the region. Given its low per capita income and staggering fiscal deficit (in 2013, fuel subsidies cost the Yemeni government $3 billion, roughly 20 percent of state expenditure), the country could not afford to subsidize energy especially since the elite got the most benefit from subsidized prices, not the poor (fuel subsidies were benefiting powerful political allies of the kleptocratic Saleh, who were smuggling subsidized oil to neighbouring markets where they would reap huge profits).

At the same time, fuel subsidies were among the few widely available social goods in Yemen. They kept down the cost of transport, water, and food, while supporting local industry.

The cash-strapped Yemeni government had been negotiating with the IMF for more than a year to secure a loan as a way to access much needed financing. The loan program would require the removal of these subsidies, but the IMF recommended gradual price adjustments and an information and communication campaign to prepare the public. Neither of these were done.

The IMF and other international donors also emphasized the need to expand the social safety net and cash transfer payments to those who would be most affected by the price increases. The United States and other donors had even increased their contributions to the Social Welfare Fund in the summer of 2014 in anticipation of subsidy removal. The Yemeni government ignored the advice.

The decision to lift fuel subsidies gave the Houthi movement, with its own axe to grind, the populist issue they needed to enter Sana’a and seize power. However the Houthi-led interim authority has not been recognized internationally and exiled president Hadi, sheltered in Saudi Arabia is still internationally recognised as the Yemeni head of state.

Operation Decisive Storm:

On 26 March 2015, Saudi Arabia announced Operation Decisive Storm and began airstrikes and announced its intentions to lead a military coalition against the Houthis, whom they claimed were being aided by Iran, and began a force buildup along the Yemeni border. The coalition included the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, Jordan, Morocco, Sudan, Egypt, and Pakistan. The United States announced that it was assisting with intelligence, targeting, and logistics. Saudi Arabia and Egypt would not rule out ground operations.

Turncoat:

In December 2017, Saleh declared his withdrawal from his coalition with the Houthis and instead sided with his former enemies – Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and President Hadi.

On 4 December 2017 during a battle between Houthi and Saleh supporters in Sana’a, Houthis accused Saleh of treason and was killed by a Houthi sniper.

Saleh had been dancing on heads of several snakes for several decades, and this time he seemed to have miscalculated.

Yemen… on its knees:

An all-out humanitarian crisis would be an understatement in case of Yemen. A 2017 UNICEF report stated that nearly half a million underage children in Yemen were on the verge of starvation, and about seven million people were facing acute food shortages. In 2016, the UN stated that, in Yemen, almost 7.5 million children needed medical care, and 370,000 children were on the verge of starvation.

…And now COVID:

In an already war-torn country, bloody with decades of civil war, the advent of COVID-19 has thrown life and preparations completely haywire. Moreover the US and World Food Programme have recently announced a cut in healthcare aid and other kinds of aid to Yemen owing to budgetary constraints, which are likely to affect several Houthi-controlled areas. Also the Donald Trump administration’s move to halt funding to WHO would severely undermine WHO’s efforts in Yemen.

In March, the UN Secretary General has appealed to the entire world for a ceasefire. “The fury of the virus illustrates the folly of war”, he said. “That is why today, I am calling for an immediate global ceasefire in all corners of the world. It is time to put armed conflict on lockdown and focus together on the true fight of our lives. … It is the most vulnerable -women and children, people with disabilities, the marginalized, displaced and refugees -who pay the highest price during conflict and who are most at risk of suffering “devastating losses” from the disease. … Furthermore, health systems in war-ravaged countries have often reached the point of total collapse, while the few health workers who remain are also seen as targets.” The UN chief called on “warring parties to pull back from hostilities, put aside mistrust and animosity, and silence the guns; stop the artillery; end the airstrikes. … And we can only do it if we do it together, if we do in a coordinated way, if we do it with intense solidarity and cooperation, and that is the raison d’etre of the United Nations itself”.

When Operation Decisive Storm started, observers and analysts thought that it was just a matter of days or months when Houthis will be defeated and Hadi can be reinstated as the Yemeni President. However, with the Houthis having the backing of Iran (Yemen being the arena of a long-standing Saudi-Iran hostility in the backdrop of a Sunni-Shia religious conflict – Houthis being Shias), the operation has dragged on for far too long than what they may have expected. Many believe that Saudi Arabia is now looking for an honourable exit strategy and COVID might have just offered them one – when they can stop their operations on humanitarian grounds. Moreover Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is also eager to focus his energies on tackling the growing economic crisis, triggered by falling oil prices, and the threat of an unmanageable COVID-19 outbreak.

On April 9, the Saudi-led coalition fighting the Iran-backed Houthi rebels announced a two-week unilateral ceasefire. The ceasefire could just be the first signs of withdrawal, and of peace – that Riyadh may be preparing to end its involvement in the war.

Tehran is yet to make an official statement on the issue. However, given the impact of COVID-19 pandemic in Iran and its sanctions hit economy, it is unlikely that Tehran would have sufficient resources to actively stay involved in the Yemeni conflict.

Since 2015, the Yemeni conflict had been a saga of ceasefires and their relentless violations. Therefore, it is difficult to believe that this time it is going to be any different unless both Iran and Saudi Arabia adhere to it. However, the malaise of COVID-19 – a common concern for all in the region – may be a reason for some optimism. At least it surely would work as a confidence-building measure, to address the bigger challenge of coronavirus. Perhaps, the pandemic could be an opportunity to mitigate, if not entirely end the Iran-Saudi rivalry in Yemen.

Conclusion:

This really is a whirlwind almost-four-decade cruise of a nation’s history – and how little things have changed – till a pandemic has forced us to stall things and take stock. Yemen seems to be a definitive textbook example of the interplay of corruption, kleptocracy, treachery, and conflict, occupying a centre-stage in the geopolitical drama of the Middle-east. It’s a history in which fortunes have turned, world organisations have flexed muscles, and neighbours have done more than tamper with internal politics. It’s a history chequered with the bigotry of religion, the jingoism of politicians, and the pathetic plight of the common man. An example of how not-to run a country.

With Snakes, Dark horse, and dances – nature have been dragged in Yemen’s doleful description – too often and too lightly – it’s probably time for Nature to now have her say. And her message really seems to be for the neighbouring countries to mind their own businesses, for world organizations to leave her alone too – to just let Yemen be. If any good comes of this pandemic maybe it will be to bring peace and progress in Yemen. Amen!

Soumyanetra Munshi is Associate Professor, Economic Research Unit, Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) Kolkata

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER