Epistemic Upheavals, Inquests and Voices of a Geographically Marginalized Researcher

Social Science Research at the Crossroad

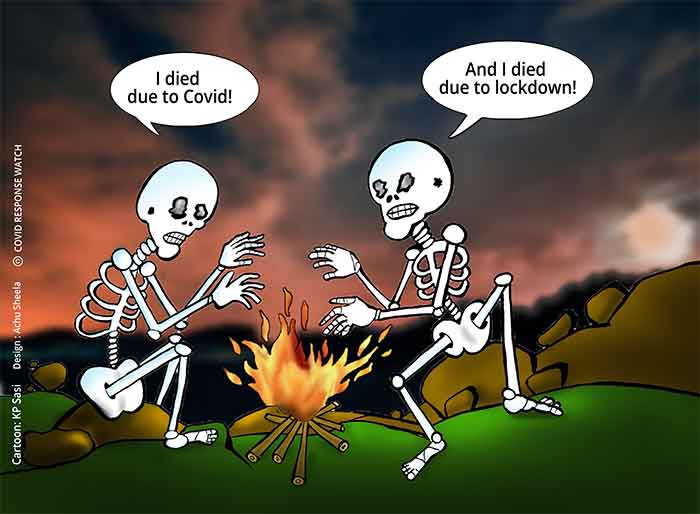

As an ethnographic researcher, I am expected to take a reflexive role— that is observing, reflecting, building up a theory and going back to the field for testing— all of which demands dedicated focus, time and resources. However, the ongoing pandemic has significantly changed the very idea of ethnography, calling social science researchers to re-think ethnography as it has posed a host of emerging epistemological and methodological challenges. It has disrupted our respective research schedule for almost two consecutive academic years now. I was in my first year of the PhD program when the pandemic hit India. Researching on the topic of ‘Militancy, Masculinity and the Making of an Ethnic Identity’, I was supposed to start my field work in western Assam with surrendered Bodo militants in the beginning of 2021. Since getting access into their lives is a difficult affair, the first entry to the field and rapport building was of paramount importance to my study. But various lockdown regimes prevented field visits and I have been stuck at home for more than a year. Indeed, the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has raised serious questions around social science research, its techniques and ethics.

The Voices of a Geographically Marginalized Researcher

While the pandemic has severely affected the research process across disciplines irrespective of class, caste, gender and religion, its impact has not been the same for all students. The first reaction to the pandemic by our university was to impose a complete shutdown of the institute. Every time there was a spike in Covid-19 positive cases, it resorted to shutdown. Issues such as lack of study materials, books, good amount of journals, fewer interactions with supervisors and with peer research groups has been significantly hindering our research these days.

Along with the institutional level challenges, I also had to deal with locational issues as my hometown is located at the Assam-Nagaland border in Jorhat district in Assam. Weak internet connectivity remains one of the biggest problems that I have had to deal along with other associated problems of being in a marginal hinterland. Indeed, as a researcher from Northeast India, I can empathize with the troubles that researchers across this region have to bear. In most of the states in Northeast India there is still a lack of proper transportation network and internet connectivity. These issues have been exaggerated more by the numerous lockdown guidelines. However, recently I have also observed through social media reporting that students across India who are from the lower socio-economic stratum and who hail from remote areas are facing similar issues when it comes to getting access to education.

‘Pandemic Ethnography’: An Epistemic Inquest

The Covid-19 contagion did not take much time to penetrate deep into my locality despite its geographical remoteness. It has spread in such a way that it has changed the entire social scene of my locality. The rumors around Covid-19 have significantly increased the issues of stigma against Covid-19 positive patients and it has largely affected the very old social structure of my place. It, however, pushed me to think about the pandemic in a different way and my epistemic enquiry has led me along with my doctoral supervisor to develop the idea of ‘Pandemic Ethnography’. I, along with my supervisor, conducted our study among the recovered Covid-19 patients and their lived experiences of Covid-19-related stigma with thick descriptions as our epistemic tool. We conceptualized pandemic ethnography as

‘….a process in which the researcher collects first persons’ or a groups’ (a person or groups who has been affected by the pandemic like the Covid-19) accounts through in-depth interviews, participant observations, field notes from the empirical world of the experiencer where the social action took place’ (S and Gogoi 2021:3 https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2021.1947019).

The challenge was, however, to break some traditional features of conventional ethnography. As an inductive method, ethnography involves producing thick and rich descriptions of a particular field setting with characteristic features like close physical proximity, close interactions and living in the particular field site for longer periods of time. However, the physical distancing imposed on us by Covid-19 and the social protocol of masking up has significantly restricted us from coming close with the research participants. Despite these bottlenecks, our reflexive field account which incorporated fruitful and ethical negotiations with the participants helped us to explore the idea of “Being-in-the-struggle”, which demonstrates how the social processing of Covid-19-related stigma becomes a reality on its own and affects the victims’ everyday social (S and Gogoi 2021: 11). Thus, the pandemic has appreciably taught social science researchers to rethink its methods and methodologies and preparedness to deal with a pandemic like Covid-19.

Negotiations from the Margin

In spite of many challenges I stayed positive with regard to my research. I adapted to new technologies with fresh enthusiasm. Thanks to my friends and my professors who helped me by sending study materials from their advanced geographical locations. Sometimes I had to wait for far too long to just login to my email account. At other times, I had to travel to the nearby town which is situated 10 kilometers away from my village just to download the study materials. However, I continued with my epistemic enquiry regarding the changes brought by the ongoing pandemic in social science research. I realized that social science is a ‘collaborative practice’, an idea that we are unknowingly distancing ourselves from.

Afterword

Covid-19 pandemic has not only affected the whole research process, but it has also affected the kind of social interaction we had before the pandemic in our university spaces. I came back to my university in the month of September 2021 and have resumed my research activities. However, the imposed physical distancing significantly affected social interactions with our supervisors as well as among research fellows. Academic discussions over a cup of tea/coffee, which at normal times is a regular sight, have significantly reduced because of the pandemic. Everyone in the university campus nowadays is afraid to come closer and talk in the shared public spaces. Indeed, as students of sociology, the imposed physical distancing of Covid-19 has forced us to rethink the many facets of ‘distance’. At the same time, it has also opened up ways to recalibrate social science research activities beyond the conventional epistemic enquiry.

Nitish Gogoi, PhD Candidate and ICMR Junior Research Fellow, Department of Sociology, Tezpur University, Assam, India Email: [email protected]