Of the many descriptions of the Japanese people readers are familiar with, e.g. industrious, polite, clean, etc., the description of Japanese as “honorary whites” may well be a first for many. Yet, it was not long ago that this term had official standing, albeit in apartheid South Africa. In the 1960s Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd determined it would be to South Africa’s economic disadvantage to subject the Japanese to the same forms of racial discrimination as other people of color since trade delegations from Japan regularly visited South Africa for business and trade. The designation of honorary whites gave Japanese visitors almost all of the same rights and privileges as whites except for the right to vote.

Interestingly, this is not the first time Japanese had been granted privileges normally reserved for whites in a white-ruled country. For that we need to look no further than the designation of Japanese as “honorary Aryans” in Nazi Germany. The Nazis bestowed the status of honorary Aryan on Japanese because, as wartime allies, their services were deemed valuable to the German economy and war effort.

Inasmuch as these designations were given to Japanese by outsiders, the question arises as to what the Japanese people, or at least their leaders, thought of these designations? Was this status welcomed or, on the contrary, was it seen as an insult to the history and character of the Japanese people who could only gain recognition in the eyes of the white nations of the world as no more than “honorary” equals, a status that could be revoked at any time and for any reason.

The answer is that Japanese leaders had been striving for something like honorary white status ever since the US forced Japan to end its isolation in the mid-nineteenth century. It was then that Japan adopted the slogan of a “rich country with a strong military” (J. fukoku kyōhei). The first of Japan’s trials and tribulations came about as a result of this slogan, for it meant that a strong military was needed for three purposes – first, to ensure that Japan would not, like so many other Asian countries, be colonized by Western imperialist powers. Second, so Japan could demand an end to the series of unequal treaties it had been forced to sign by the more powerful Western powers. Third, so Japan itself would be in a position to join the Western powers in creating an empire of its own.

Japan’s first major attempt to enlarge its empire came with its victory in the first Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95. The terms of the peace treaty Japan signed with China in April 1895 included turning over the Liaodong Peninsula, Taiwan and Penghu Islands to Japan “in perpetuity.” Russia, Germany and France, however, immediately objected to the treaty’s terms, forcing Japan to give up its claim to the Liaodong Peninsula on the Chinese mainland. Although the Western powers were prepared to allow Japan to take over what were then relatively minor islands off China’s coast, they would not countenance Japan interfering with their own imperial prerogatives on the Chinese mainland.

With the taste of victory in its mouth, Japan’s next objective was the colonization of the Korean peninsula and, if possible, advancement into Manchuria. This led Japan to launch a surprise attack on Tsarist Russian naval forces stationed at Port Arthur in China in February 1904. Tsarist Russia also had its eyes on Korea inasmuch as it sought warm water ports for its Pacific fleet.

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 marked the first conflict between a non-Western, non-white, imperialist nation and an established Western imperialist power. Surprisingly, this time not all Western nations backed Russia. Notably, the UK provided strong financial and diplomatic support to Japan, for it saw the opportunity to prevent its Russian rival from further economic advancement on the Asian continent. The US also sided with Japan while Germany supported Russia. American Protestant Christian missionaries in Japan were particularly vociferous in their support of Japan, identifying the Japanese people as more “Christian at heart” and Caucasian than the Russians were. The ambitions of Western imperialist nations, including their citizenry, were by no means always united, for they competed for influence among themselves as well.

The US had a second goal in backing Japan, for it had only succeeded in forcefully acquiring its first colony in Asia, i.e. the Philippines, in 1898. With Japan in control of Taiwan, the US was concerned that sooner or later Japan’s ambitions might turn further south, threatening its continued hold on the Philippines. Thus, the Treaty of Portsmouth ending the Russo-Japanese War in September 1905, contained a non-publicized pledge made by US and Japanese representatives, known as the Taft-Katsura Agreement. In it, the US stated it would have no objection to Japan’s colonization of Korea in return for a Japanese commitment not to threaten American control of the Philippines. At least at that point, both the US and Japan could agree on how to divide the spoils of imperial conquest.

The Taft-Katsura agreement marked US acceptance of Japan into the imperialist club, albeit still as a decidedly junior player. During WW I, Japan took advantage of this position to form an alliance with the Allied Powers and played an important role in securing sea lanes in the West Pacific and Indian Oceans against the Imperial German Navy. As its reward at war’s end, the Japanese empire was allowed to expand its sphere of influence in China, particularly in Manchuria, and gain recognition as a great power in postwar geopolitics.

While Japan was expanding its empire in Asia, a rather incongruous cultural phenomenon had long been at work within Japan. The goal of this phenomenon was literally to “leave Asia” (J. Datsu-A-Ron). This goal was first articulated in an anonymous newspaper opinion editorial, widely attributed to Fukuzawa Yukichi, written in 1885. The thrust of the article was that Japan should promote Western-style modernization by cutting ties with what were considered to be the backward countries of East Asia, i.e. Korea and China. Further, as Japan moved closer to European and American powers, it should disassociate itself from Asia as a whole, going so far as to deny Japan’s identity as an Asian country.

Promotion of the idea of leaving Asia occurred in tandem with the “bunmei kaika” (civilization blooming) movement, definitely advocated by writer and educator Fukuzawa Yukichi. In its extreme form it led to the idea that anything from the West was good. The result was the wholesale adoption of Western culture, from food to education to dress, all the while discarding customs and manners from Japan’s feudal past, many of which had their origins in China and Korea. The end results of these two movements were not only growing disrespect for other Asian countries which, in Japan’s eyes, refused to adopt Western “civilization,” but a belief that the Japanese were a superior race.

Japan had become a “civilized nation” just at the time Western imperialist nations were reaching the zenith of their power, not simply due to their industrialization (which Japan copied) but also because of the wealth derived from their overseas colonies (a policy Japan also adopted). As noted above, at least for a time, Western nations were willing, albeit somewhat grudgingly, to make room for another player in the imperialist game, even finding Japan could sometimes make useful contributions to their imperialist goals. However, by the 1930s, in the wake of the worldwide Great Depression of 1929, Japan sought to completely takeover the largest piece of territory by far – Manchuria.

Had Japan been willing to share Manchuria’s wealth, the Western imperialist countries, led by the US, initially showed some willingness to allow Japanese industry to play a leading role in developing Manchuria’s vast mineral wealth. Japan, however, refused to do so, for its industrialists wanted Manchuria’s riches entirely for themselves, as well as agricultural lands that its burgeoning population could colonize. Although the US spoke of the need to protect China from Japanese encroachments, it made no similar protestations of Britain’s control of India, Burma, etc., or France’s control of Indochina, or Holland’s control of Indonesian oil. Western imperialism was acceptable, but Japan’s landgrab had to be stopped.

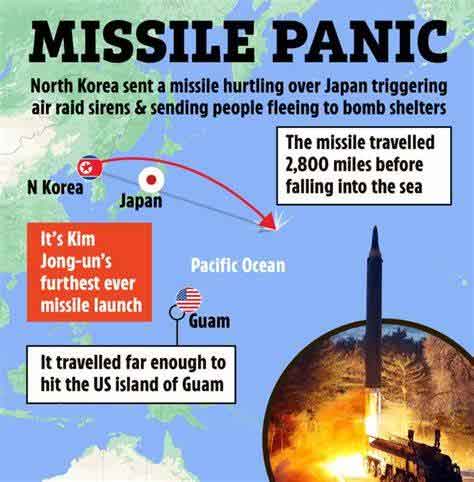

In short, the defeat of the Japanese empire in Asia at the end of WW II was a method to teach Japan its proper, i.e. subordinate, role in the West’s pecking order. Thus, in the postwar era, Japan effectively became an American dependency where even now, some seventy-seven years later, approximately 55,000 US military personnel are stationed, with Japanese taxpayers contributing more than $2 billion yearly to their support. US military bases in Japan demonstrated their importance by the crucial role they played in providing logistical support for both the Korean and Vietnam Wars. So important were these bases that without them it would have been difficult if not impossible for the US to have fought in either country. The same may be said of a future possible, if not increasingly probable, war between the US and China over Taiwan, though this time it is anticipated the Japanese military will fight on the US side.

Japan learned its lesson well. Never again in the postwar period would it challenge the “king of the mountain” in military or diplomatic affairs. In return, the US granted Japan permanent status as a nation of honorary whites, making space for Japan to survive, even thrive, economically so long as it didn’t challenge overall US hegemony, not least of all in Asia.

Japan’s current 100% identification with the US policy of holding Russia solely responsible for its alleged “unprovoked” aggression against Ukraine is but the latest manifestation of its postwar subservience. This, despite the fact that when the call went out to sanction Russia, most of the non-Western world, i.e. the ‘colored nations’, ignored it, though not, of course, Japan.

In addition, as demonstrated so clearly by the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, the US would never allow neighboring countries like Canada, Mexico, let alone Cuba, to join a military alliance with Russia or China directed against it. Once again, however, ever subservient Japan willfully ignores the double standards of the US, backing its refusal to acknowledge responsibility for having provoked Russia to invade Ukraine however objectionable that invasion may be.

The trials and tribulations of a land of honorary whites seem endless.

Brian Victoria, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies