“I don’t think rape is about sex. It is about violence and the need for power…

“We talk of sexual violence. We don’t talk enough about patriarchy. We don’t talk enough about equality. We don’t talk about discrimination…

“Quotidian violence to women is normalized, whereas rape is moralized…

“Dalit village women have never been given space besides picking up cow dung or rag picking. They have no training. How will their stories be given space in the media. How do they make a #MeToo movement?

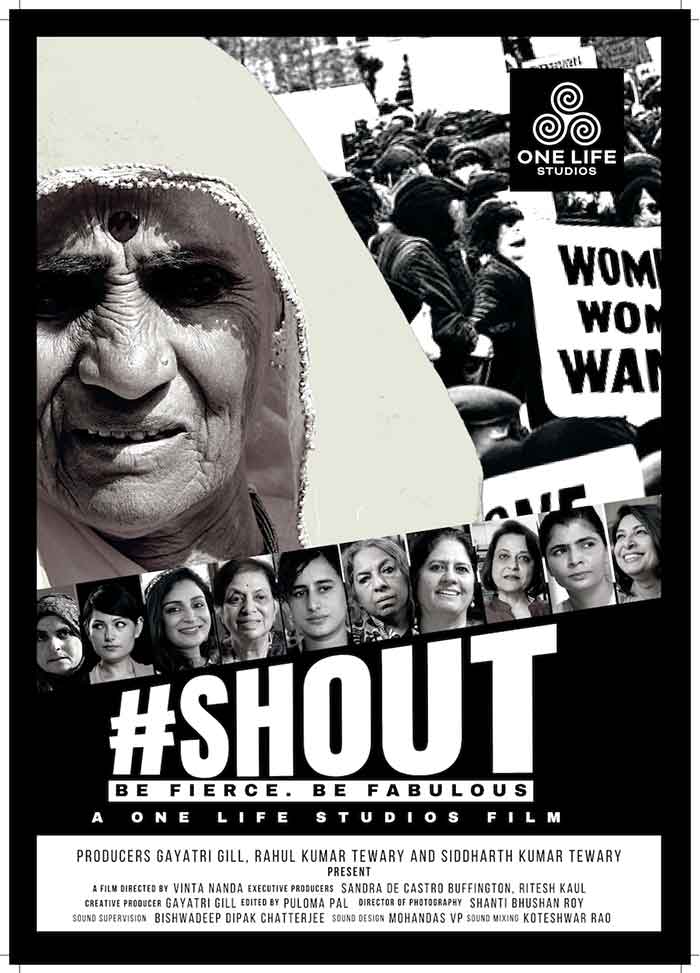

Packed with incisive statements and insightful reflections Vinta Nanda’s #Shout is a documentary that explores the #MeToo movement, placing it in the overarching gender and patriarchy discourse.

Nanda, who was vocal during the movement, clarified in a brief conversation with me, she didn’t however want to a make a film adding to her story. She wanted instead to pick up the threads of the #MeToo days and garner a greater understanding of the basics and what had gone on before. It was necessary, she said, to go back into time and explore spaces. How did the #MeToo movement, originating in the internet and social media, derive its locus standi to demand safe working places and mandatory implementation of Prevention of Sexual Harassment (POSH)?

It would be wrong, she said, to ignore the social ferment of the early feminist days and the grassroots activism. Her research led her to Bhanwari Devi, the saathin and government employee of Rajasthan who was gang raped for doing her duty_ stopping the child marriage in an upper caste community. It was Bhanwari’s struggle and the collective decision of various non-governmental women organizations and movements that led to explorations in law and brought about the Vishaka guidelines or procedures to be used in cases of sexual harassment promulgated by the Supreme Court in 1997.

The film acknowledges this valuable historical context with Justice Sujata Manohar, explaining how the law was premised on United Nation treaties on women’s safety and equality, thereby making it mandatory for work places to have committees to address issues of sexual harassment.

It is heartening to hear a spirited Bhanwari Devi, in the film, assert her rights. “I was young and employed by the government to help young girls. The government should have helped me. But it was silent.”

Or then to hear her echo the humiliation that women face when they dare to rise their voices against sexual violence. She recollects how she was often asked during the legal proceedings whether she understood what rape is. “I know it better than anyone else…Who gives you the right to ask..”

It is a bitter reflection on the inadequacy of the legal system, however, that whilst Bhanwari Devi’s agony brought about legislation, it could not deliver her justice. The accused persons in her case were acquitted.

But as Urvashi Butalia, feminist writer, publisher and activist points out the times were also such that “we had a State that responded to street level protests. It listened to people and said what are you protesting about. And these are the reasons why we were able to succeed.”

(I wonder if it is a measure of how far we have regressed when one looks at the plight of the women wrestlers and how the State and the public has responded to them? They say they have withdrawn from street protests.)

Nanda told me her film can be viewed as perspectives before Bhanwari Devi _the feminism of the nineties _ and then after. In 2018 there was a new generation of urban empowered, advantaged women. They were financially independent, had sexual partners of their own choice and were pursuing careers successfully. But why and how was sexual harassment happening?

The spate of reactions and the crucial gender questions, which were raised, form the backbone of the film, which has little commentary. Just a powerful flow of narratives through the lenses of people from very diverse socio- cultural backgrounds. Talking about their own personal experiences, they dissect how culture, media, traditions, religion, politics and conflict help foster this violence.

We hear from the Kerala nun who accused a bishop of rape, film stars who accused Sajid Khan, journalists who confronted former editor and now political leader MJ Akbar and Tara Kaushal who researched and wrote “Why do men rape.”

As the film unfolds we understand how it is patriarchal power at the crux. Nanda told me how this patriarchy is so pervasive in society, in behaviour and in attitude that “sometimes even we feminists have not listened and made that effort to recognize it. We land up supporting the system.”

Bolstering this belief of how our society and culture perpetuates such attitudes is Ravina Raj Kohli, media professional, who in the documentary makes the revealing observations. She says that the people who make decisions about how to shoot a rape scene, those who script a character about who is a rapist or a victim, those who showcase women or who create stereotypes are professionals “like us.” They come from a similar background, education and hold positions of power.

Yet, Nanda also affirms that when women come together and decide to do something it can happen. Like the Meira Paibi (women’s social movement in Manipur) who, in a startling display of performative politics, had stripped outside the headquarters of the army at Kangla, Manipur on July 15, 2004 to protest the sexual violence of security forces. A young woman Thangjam Manorama who was abducted, gang raped and murdered had been the triggering factor. It is an exploration of the violence brought about in conflict regions by state agencies using it as a weapon of war.

Another remarkable story is that of Bant Singh, a Dalit, of Mansa Punjab, who fought for the rights of landless labourers and for his minor daughter who was raped by some men belonging to the dominant caste. The film is forthright in exposing the politics and casteism of Dalit rapes. The landlord’s son making it out with a Dalit girl is seen almost as a coming-of-age ritual and yet no one winces, explains an activist.

Bant Singh however decided to fight head on after the Panchayat sat on his complaint and tried appeasement with promises of land. One day he was savagely assaulted by a gang and suffered such horrendous injuries that his arms and legs had to be amputated. His wife narrates how he wept a few tears but vowed not to back down.

Bant Singh’s words ring out powerfully almost like a battle cry

“My hands are cut/My tongue isn’t

I will sing…”

And his daughter gets justice. Eventually a court convicted the men. It was the first conviction of rape by upper caste men in a rape of its kind.

Freny Manecksha is a journalist