Soon after Narendra Modi came to power in 2014, one of the stranger promises he made was that his regime would ‘end 1200 years of slavery in India’.

Mr Modi is known to be a calculating politician but is not exactly a mathematical genius. So, no one knows how he arrived at the precise number ‘1200’.

He perhaps added up the years from the time of the Arab conquest of Sindh in the 8th century, plus the period of Turkish and Mughal rule and the two century reign of British colonialists over the Indian sub-continent. (Maybe, he even added in the Nehruvian decades and Vajpayee years).

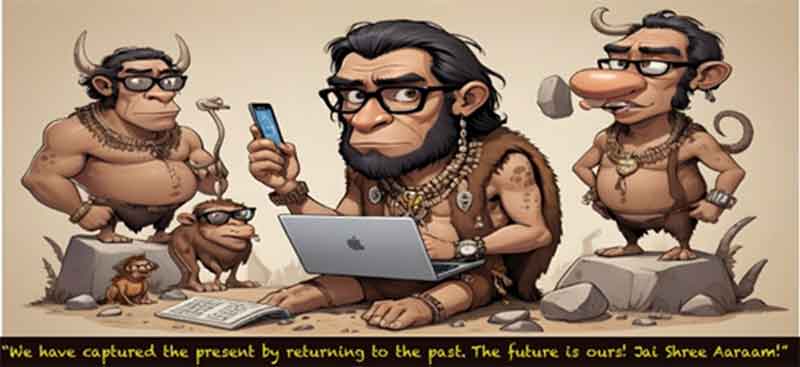

Whatever his dodgy arithmetic I was gripped by a truly scary thought -what if Narendra Modi was not bluffing and had actually delivered on his promise? Has his regime– in the last decade – really taken the entire country back to somewhere between the 8th and 10th century – the mythical period ‘before slavery’?

To confirm this, I checked out a broad description of the political, social, cultural and religious life from 1200 years ago across the sub-continent to compare with our own times. The comparisons are not perfect and obviously many things in contemporary India are quite different from what existed in the past.

And yet it is hard to miss the similarities. The bad news is that we are indeed back in the age of Hindu monarchs, warlords and priests running the show. The good news though is that we are finally free to be 100 percent pure and authentic Indians and leave behind the pretence of being civilized citizens of the world.

Let me start with the power dynamics at the level of the Indian sub-continent. Obviously, there was no one ‘Indian nation’ in those days – divided as the sub-continent was between various kingdoms. What is interesting though is the geographical areas of influence of different rulers still broadly overlaps with what exists today.

Back then, the most powerful empire was that of the Gurjara-Pratiharas, which extended from the west to east of India, upto Bihar. While the seat of power was Kannauj, now in Uttar Pradesh, the origin of Gurjaras themselves was from somewhere else, with some claiming they entered India in the wake of the Hephthalites (White Huns or Hunas) invasion of India in the 5th century[i].

Incidentally, the modern state of “Gujarat” derives its name from the ancient ‘Gurjaratra’ – or land of the Gurjaras. Just like the current Modi regime the Gurjara empire had little presence south of the Vindhyas, which was dominated by the Rashtrakutas, Chola and Pandayan rulers. In Bengal the Palas, who were staunch Buddhists, reigned (though there is no evidence of any feisty woman ruler in power there those days).

What was common to all these monarchs though was the way they depended on warlords at the local and regional levels to obtain power or hold on to it. These warlords, known as samantas or mahasamantas, commanded their own armies and could support or challenge the authority of the monarchs[ii].

This is not very different from how political parties, across the spectrum, operate in India today, by wooing influential local leaders – each in it for their own benefit – to help them contest elections and form governments. There is no doubt at all that MPs and MLAs of the current Indian electoral system – made up of a mix of those with caste, money, muscle or even celebrity power – are really warlords of the past in the modern packaging of ‘elected representatives’.

And as in the 9th century, decisions regarding state or public affairs are decided by different lobbies through intrigue in and around the Emperor’s court – also called the Prime Minister’s Office. While in the past there was no parliament at all, now a building by that name exists but has been reduced to complete irrelevance.

Just like a millennium ago even today – after a decade of the Modi regime – there is not even a pretence of democracy or rule of law left. Whether one gets justice or not depends solely on whether you are for or against the regime. Things are even worse for those who do not belong to the ‘right’ caste or religion.

Talking about caste, not very surprisingly, one’s position in the social hierarchy in the 9th century completely determined one’s occupation, marriage prospects, and social interactions[iii]. The concept of untouchability, which placed certain communities outside the caste system, was also prevalent[iv].

In contemporary India too – caste continues to be the most important factor in deciding not just the fate of ordinary citizens but various institutions and the future of the nation itself. For example, since 1947 Independence the Supreme Court has been dominated by Brahmins – despite their forming a tiny percentage of the overall Indian population.

Out of 50 CJIs appointed so far, at least 16 were Brahmins (including the current one) – which means the percentage of Brahmin Chief Justices since Independence is around 32%[v]. In a reply to a question in the Lok Sabha Union law minister, Arjun Meghwal last year stated that three out of four judges appointed to high courts in the country since 2018 were from upper-caste communities[vi].

Again, when it comes to wealth a study in 2019 showed that only 22.3 per cent of the country’s higher caste Hindus own 41 per cent of the country’s total wealth. In sharp contrast India’s Scheduled Tribes, who form 10 percent of the Indian population, altogether own only 3.7 per cent. These figures seem straight out of the pre-medieval past.

On the religious front the 9th century saw intense competition for influence over kings and the state machinery between Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, which were the major religions of the time[vii]. Although Buddhism (the equivalent of the Nehruvian worldview today), still had a significant presence, particularly in eastern and southern India but was in overall decline[viii]. Jainism also had a notable following, especially in western and southern India[ix].

The churning within the various schools of thought and practice that formed Hinduism was most interesting. This was the period when the Bhakti movement, which emerged in southern India, was reviving and reworking old Vedic traditions to take on the challenge of Buddhist and Jain rivals – both of which denied the authority of the Vedas.

And within the Bhakti movement too Vaishnavism, Shaivism and various Shakti goddess cults competed with each other for winning over lay followers, the rivalry sometimes taking a violent turn.

The competition within and among religious groups historically has never really been about principles or philosophy per se and mostly linked to economics. The 9th century for example was a time when temple-building flourished all over the country. Returns were good for anyone – like feudal lords, monarchs and merchants – willing to invest in the business and different deities were like brand ambassadors used to capture a share of this booming market. Naturally, quite often these business rivalries turned quite ugly.

Uncannily, Modi’s India too has been a period when the business of new temples, religious TV channels, spiritual gurus, the pilgrimage tourism industry, traditional medicine, and yoga has been extremely lucrative. The politicisation of religion over the last few decades has brought in even more money into the sector with every party vying with the other to spend on festivals, appeasing the priestly classes and advertising their devoutness through the mass media.

And just like in the 9th century, today religious leaders and establishments openly dictate terms and hold sway over those in power. Politicians in turn compete with each other to project themselves as the most ‘devout’ bhakts of different Hindu gods. The theatrical inauguration of the new temple in Ayodhya recently showed that Modi even thinks of himself as a devaraja or ‘God King’ from the ancient past.

However, even today, lurking in the shadows of this grand revival of Hinduism is also resentment at the domination of certain religious establishments over state patronage or status and media attention. The decision of the four Shankaracharyas – from the Shaivite tradition – to boycott the opening ceremony of the new temple to Lord Ram, an avatar of Vishnu, is indeed another blast from the past

I am sure by now many of you think I have carried this comparison between the India of today and that from the 9th century a bit too far. After all India is still a modern Republic with a written Constitution, separation of powers between key institutions, an electoral democracy where peaceful transfer of power is still possible, Vande Bharat trains, the Chandrayan mission and a free media.

You are watching too much godi media bro. Look out of the window. We are now in the 9th Century, which is our future.

Satya Sagar is a journalist and public health worker. He can be reached at [email protected]

[i] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Origin_of_the_Gurjara-Pratiharas

[ii] Chattopadhyaya, B. D. (1994). The Making of Early Medieval India. Oxford University Press.

[iii] Thapar, R. (2002). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press.

[iv] Jha, D. N. (1967). The Feudal Order: State, Society and Ideology in Early Medieval India. Manohar Publishers.

[v] https://www.barandbench.com/columns/disproportionate-representation-supreme-court-caste-and-religion-of-judges

[vi] https://thewire.in/law/over-75-of-high-court-judges-appointed-since-2018-are-from-upper-castes-centre

[vii] Flood, G. D. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press.

[viii] Keay, J. (2000). India: A History. Grove Press.

[ix] Dundas, P. (2002). The Jains (2nd ed.). Routledge.