Waking up from sleep has usually been a refreshing exercise. Like, returning home after a hard day of work. But, not anymore. While we do not celebrate the little pleasures that life brings, it is only when bliss gives us a miss, that we begin to take note of how the quotidian is more than just routine. When the second wave of COVID-19 virus hit India, with renewed vitality, I was not nestled in my happy place, my home. I still am not. I am doing ethnographic research in the villages of a tribal-dominated district in West Bengal. While I am working in villages, as part of my academic enquiry, I stay in a rented room in the town nearby. When the news of the second-wave began to capture headlines once again, my anxiety level soared, unsure of the medical infrastructure around me, seeing it collapse every day at a pace unmatched and with news pouring in of shortage of emergency supplies. Death bodies piling up at pavements and crematoriums added to the trauma. But what was harrowing or rather to say alarming was the way in which the perception of people around me started to change regarding the work I am doing and its potential consequences on not mine, but on their health. It was then that I got initiated to two other viruses that feeds on and in turn feeds the coronavirus in, stupidity and privilege. I never knew that I had to battle it out on all three fronts!

The pandemic has widened inequality across the globe. Both economically and even more, socially. While economic inequality can be measured by employing scientific tools, in a society that is turning increasingly unscientific, social inequality can only be experienced. This article intends to lay bare one such experience, in its numerous layers, involving how a research scholar working among the poorest poor in the villages of a small district in West Bengal, is gazed at by people living in town, across class and caste, during a pandemic. While the pandemic does not discriminate, it brings forth the divisions that run deep in the Indian psyche. While this in itself is discomforting, experiencing it on a day to day basis makes the struggle grimmer.

Very strangely, Indian masses take pandemic seriously only when it hits headlines, becomes prime time news and appear on front pages of newspaper. When I came to the place of my research at around February, people were roaming around without masks and those who were masked up, were either ridiculed or served with unscientific conspiracy theories. My land lady, in the beginning, was particularly excited to host me, showing a lot of interest in my research, asking me questions about my experiences among villagers in the field, while sometimes also sharing her own experiences which she thought would help me know the place and its people better. After the pandemic hit headlines and thus also hit her, she first urged me to get vaccinated. On learning that I was not eligible, (till yesterday when it was made available for every citizen above 18 years) for the same, she showed concern and tried to at first caution me about how the second wave is worse that the first wave. I complied and assured her of maintaining hygiene and wearing masks. A few days later, after I returned to the room, from my field site, tired of the excruciating heat outside, she called me upstairs to caution me about how it is dangerous to regularly visit villages during a pandemic, when the rate of infection is going up every day, as villagers, being poor and thus, ‘unhygienic’ (nongra), are the real source of infection. Agitated at the very idea, I offered to at once leave her place, and shift to some temporary accommodation nearby till I find another rented room. I also lectured her about how morally reprehensive it is to blame a section of the population that are worst hit not by the disease but by its economic and societal fallouts. I reminded her of her privileges, but then I realized that she remembers only those. She requested me to stay and I stayed back thinking that possibly my message has been conveyed. But, I was wrong! The pressure on me kept escalating and soon, it began to take a toll on my mental health. I was made to feel like a super-spreader, carrying the virus with me, wherever I am going, and I started getting nightmares. In fact, I avoided sleeping for a few days and instead took to writing to heal myself. I remember staying back in one of my field sites for a night. After my return I was told that I should not only take a bath but that I should wash my clothes and allow them to dry inside the bathroom itself so as to avoid any risk of a potential infection. I was given lessons on how the virus is actually spreading from bare feet, and how villagers don’t usually wear slippers and roam around bare foot. While all of this came from concern and were therefore cautions I was told, I, on my part was awestruck by the idiocy that impregnates privilege, idiocy that only increased with the snowballing of the disease: coronavirus since to have leased a fresh lease of life to the stupidity virus too. The maid of the house, who washed my clothes also came up to me to tell me how I should soak my clothes in antiseptic (which seemed a rational suggestion though) before she washes them because I was visiting villages and she was unsure of how hygienic villagers are. That came as an eye opener. Till that time, I was analyzing the situation through the category of class and its associated privilege, how elite sections of the population routinely discriminate against those whom they live off. But not quite! The town-village division, the India-Bharat stereotyping just got real for me and I bunked the idea of leaving my rented room and instead decided to fight the battle from the room.

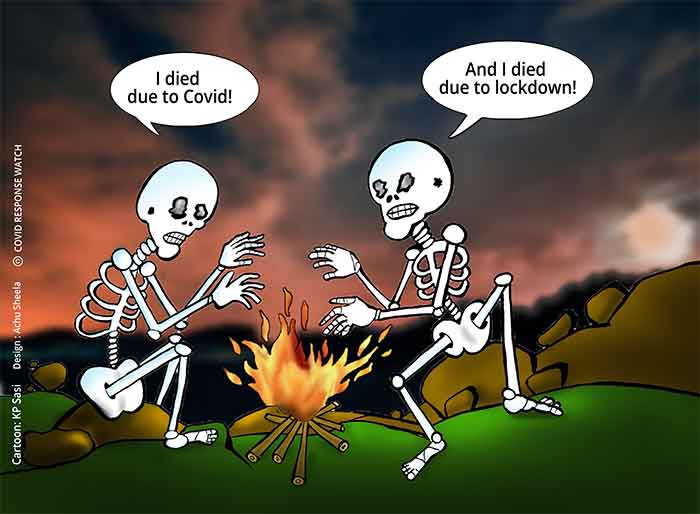

The game is on. Its dimensions are dynamic. The explanations of how it is potentially dangerous to visit villages are hitting low with each passing day; but, they are skeletally moving upwards in the sense that now, I should also be cautious of accepting this from villagers because their hands are ‘dirty’, for they are seldom washed and never sanitized! Meantime, I am battling it out in two levels. While I am absolutely cautious of the coronavirus without, I am also fighting with the privilege and stupidity virus within. It is not easy. But, was it meant to be easy anyway?

Shamayita Sen is currently pursuing MPhil in Social Sciences from the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. Her current research interests encompass a focus on tribal studies, social anthropology, agrarian sociology, development, and inequality. The author can be contacted at [email protected]

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX