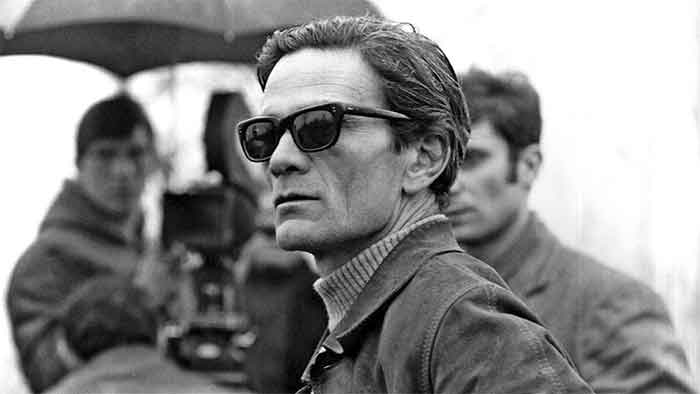

Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975) would have been a centenarian this year had he not fell foul of an extreme-Right conspiracy at the age of 53. Murdered on the beaches of Ostia, near Rome, ostensibly for his homosexuality, Pasolini passed into a world where there is no death, only homages to creative subversion or heated controversies born more of social prejudice combined with political enmity than any attempt to understand the gravitas of the issues that haunted him like the Furies all his life.

Perhaps the most distinguished Italian holistic intellectual to have been a consistent supporter of Pasolini was none other than the novelist and short story teller Alberto Moravia, a cineaste of no mean order. Considering the comparative popularity of the varied art forms in which Pasolini engaged himself, it is perhaps understandable that the world should remember him as primarily a filmmaker, forgetting or glossing over his enormous achievements as an unforgiving poet of the lower depths; of the godforsaken shanty towns whose proletarian or sub-proletarian inhabitants had learnt to accept deprivation and disgrace as their inevitable fate. If occasional defiance were to rear its head, it would be instantly scotched by a combination of tyrannical forces, from the bourgeoisie to the church to the media and the political establishment to, perhaps most sadly, enemies lurking within the fold.

The days in which Pasolini came of age, the seven hills of Rome bristled with the anger of the popular classes, and the Tiber overflowed with disappointment at the triumph of the culture of complicity of the wealthy and powerful. Together, these provided Pasolini with the wherewithal to sculpt his protest on celluloid in an idiom absent in Italian cinema before or after him. The quintessential rebel that was Pasolini, he would not, like Spartacus before him, take lightly the slavery of the mind and the bondage of the body to which the disenfranchised had been condemned. In the end, both these iconic figures came to a violent end for their polemical and sexual overenthusiasms. Deeply offended by the insult of having to co-habit with undeserved injustices, they had no choice but to fly in the face of death foretold.

Moravia’s observations on Pasolini the poet are worthy of recall not only because he himself was an exponent of high literature frequently peopled by lowly characters, but for his deep knowledge of, and support for a certain kind of “people’s cinema” that rested on explosive possibilities of deliverance for malcontents in search of sighting the sun and thereby defeating the dark. Moravia’s admiration for Pasolini’s poetry knows no bounds: “Pasolini is the greatest Italian poet in the second half of the 20th century. One poet is not worth more than another. But Pasolini wrote more, and more importantly than the others. Pasolini was fated to grow up during a disastrous period of Italian history, at a time of unparalleled catastrophe: a military debacle, with two armies fighting on Italian soil. At the same time, the industrial revolution was drawing millions of men to the cities, away from the peasant civilization which Pasolini loved and in which the roots of his poetry lay. Here then we have two of the main themes of Pasolini’s poetry: lamentation for the devastated, prostrate and humiliated nation; and nostalgia for the lost peasant”.

Reading Moravia on Pasolini almost half a century after the latter’s death, it is difficult not to be struck by how well the litterateur understood the literary outpourings of his assassinated countryman, making him place them above his films, but without denying in any way their uniqueness and the purity of their grandeur. Where Pasolini’s critics, conservative and constipated, could see only obscenity and perversion, Moravia, or the poet, critic and translator, Giovanni Raboni, delighted in a return to a medieval past which could be both glorious and cruel.

Moravia: “Pasolini expressed his main themes (of post-WW2 humiliation, or regret for a lost past) not only in poetry but also through his novels and films. Indeed, his work in the cinema must be placed immediately after his work as a poet – and ahead of his novels – for its ambitious scope and the quality of the results he was to achieve … In cinema, using the tools of the medium, Pasolini translated into images what we may call his medieval vision, which came to him from the furthest origins of Italian literature and painting. When, for example, he treated his contemporary situations in his first film Accattone, the style of his narrative echoed the stories and frescoes of 13th and 14th century Italy. This is true not only in the films in which Pasolini attempted, with extraordinary success, to translate the tales of Boccaccio, Chaucer and the Arabian Nights, even St. Matthew’s Gospel, into the idiom of cinema. It is also the style of Procile, Mamma Roma, La Ricotta, Edipo Re, Uccellaci e Uccellini, Teorema, Salo o Le 120 Giornate di Sodoma, as well as Accattone. In these films, the rough grandeur of the narration is enhanced by evocations of other great directors (from Eisenstein to Mizoguchi), and is marvellously suited to the solemn themes that Pasolini tackles: love, death, redemption, revolution, ideology, myth and miracle”.

Often working with devastating effect around his belief in the dialectics between politics and religion, Pasolini’s films have remarkably stood the test of time, albeit in well-defined radical circles. But he is, arguably, at his best in what is commonly regarded to be his most distinguished work, namely, The Gospel according to Saint Matthew, where Christ is a revolutionary “weaponising” peace and the brotherhood of man in an ambience of violence perpetrated by the Romans working in league with the Jewish priestly class. Pasolini argued that given the socio-political conditions in which Christ lived and worked, what other course than turning the other cheek to the oppressor could he have chosen to reach his message effectively to his subaltern constituency. When an ossified section of the Italian Communist Party took exception to Pasolini’s choice of subject, he retorted that he would be a fraud if, even whilst keeping in mind his Marxist persuasion, he were to deny or disown the history and tradition of the Judeo-Christian civilization to which he had been born and which had been in operation for centuries in the land of his birth.

In this context, Pasolini appears to have been quite clear in his head about how he saw Christ. He “humanised” Christ to the extent that his film was anathema to the conservatives of the Catholic clergy, but more than welcome to enlightened Christians on an international scale. For instance, Bud Keiser, the American producer of Romero about the martyred Salvadoran liberation theologian, is on record that Pasolini’s realistic interpretation of the life of Christ still holds good from a cinematographic point of view precisely because it stays away from being reverential and, in fact, is rather skeptical in tone. Where most films to do with Christ or the saints end up, in a sense, mummifying them, something as special as The Gospel according to Saint Matthew gives us a spiritual figure throbbing with life complete with possibilities of failure and atonement.

Here, it may not be out of place to comment on how Pasolini and his mentor, Roberto Rossellini (1906-1977), were one when it came to making films that held possibilities of showing moving mystical/spiritual qualities. In 1950, fourteen years before Pasolini’s ‘Gospel’ film, Rossellini made Francisco, giullare di dio (The Flowers of Saint Francis). This important but little-discussed film (in at least India) about the medieval saint known for his love of birds and helpless animals was co-written by Federico Fellini (1920-1993) and based on two 14th century novels. While right-wing Italian critics with a consistently expressed aversion to Rossellini’s neo-realist classics beginning with Rome, Open City (1945), panned Francisco with one of them going to the extreme of calling it “a stupid film”, both Pasolini and Truffaut, two very dissimilar filmmakers, were full of praise for it. Andrew Sarris, the eminent critic, expressed his admiration in no uncertain terms. Pasolini, whose enthusiasm for certain ancient to medieval aspects of the culture and civilization of his land was as intense as for the Marxist interpretation of history, called Francisco “among the most beautiful in Italian cinema”.

The Vatican, otherwise known to take a dim view of Rossellini on account of his more than one marriage and numerous “affairs” or his declared reservations about institutionalized religiosity, perhaps felt compelled to go public with its approval of the Left-leaning director’s interpretation of the saintly life mixing restraint with reverence. For as long as he lived, which was for a pitifully short period of fifty-three summers, Pasolini was among Rossellini’s most ardent admirers. On his part, Rossellini never ceased to talk highly of Pasolini’s memorable portrait of Christ, which arouses awe to this day on account of the mastery and conviction with which he made the son of Mary and Joseph accessible to both the elite and the subaltern viewer alike. Like all great filmmakers, Rossellini inspired many outstanding younger poets of cinema. In his own country, it was Pasolini who showed in his films, more eloquently than anyone else, many of the cinematic preoccupations of the iconic figure who, along with Vittorio de Sica, Luchino Visconti and Cesare Zavattini, founded the neo-realist movement.

Looking through the lens of the so-called guru-shishya parampara, Italian variation, this writer tries to understand the common interest in India that the two harboured. Both Pasolini and Rossellini made documentary films on India, reflecting their appreciation of a land of ancient achievements and many contradictions, but in markedly different ways. Rossellini, a man of refinement and deep interest in ancient cultures and civilizations, felt a passionate pull towards India, in both its hoary past and its proud but troubled present following the departure of the British. When in the closing years of the 1950s, he put forth a proposal to make a film on India and its diverse peoples, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, more an aesthete and statesman than a run-of-the-mill politician, showed active interest in the venture. The director was promised all official help and the Films Division was advised to put its rich archival collection at the disposal of the visiting master. That film, called India and made in 1958, proved to be a work of great artistic merit, combining documentary and dramatic elements with masterly ease in an attempt to tell a story of co-existence of tradition and modernity honestly and well. The intention of the film was such as to remove in a persuasive tone, the false impressions existing in many European minds about a country steeped in superstition and backwardness with hardly anything progressive to offer.

Rossellini had some detractors in the West largely on account of his unshakable faith in the premises of neo-realism. However, it was precisely this faith that endeared him to his most committed supporters. Among his foremost admirers was Jean-Luc Godard, who is on record that he found Rossellini’s films beautiful not in any superficial sense, but because the best of them were suffused with the beauty of truth. The truth contained in everyday realities of common folk appealed to Rossellini’s artistic sense and humane sensibility. It is this philosophical approach to the politics of living with as much dignity and honour as possible that make his films, whether it is his war trilogy (Rome, Open City; Paisan; and Germania, Anno Zero), or his documentary on India, glow with a rare incandescence. Perhaps, because of this engagement with a combination of desperation and dreams that Rossellini is said to have been not just a realist, but the “magician of the real”.

But Pasolini, true to his nature, went about making his film on India – a travelogue about “a country of contradictions” – in a style that reminded the viewer of a dense and daring prophet more than anything else. It was shot in Bombay and New Delhi in December 1967 and January 1968, a decade or so after Rossellini made his film. Produced by RAI Radio Televisione Italiana, Pasolini himself did the photography for this 34-minute documentary called Appunti per un film sull India (Notes for a film on India).The film describes the plan to produce a film based on an ancient Indian legend. Unfortunately, the plan was never realised. Thinking about the proposed film, Pasolini wrote: “A Westerner who goes to India gets everything but gives nothing. Whereas in reality India who has nothing gives everything, but what?” That was Pasolini – frequently, if not always, resorting to riddles to make his point.

Filippo La Porta, a wise old Pasolini scholar, hobbling on a walking stick yet full of good humour, who this writer had the privilege of meeting at Nandan, the West Bengal Film Centre, in 2001, in connection with a roving Pasolini retrospective and seminar, had this to say regarding the “ancient Indian legend” mentioned earlier: “Shortly before his departure for India, Pasolini remembered a distant moment from his childhood when, back at home after going to the cinema with his parents, he began to leaf through a book they had given him and was left spellbound by one of the illustrations. It depicted a young explorer, lying face upwards in the jungle and being mauled by a huge tiger. This image would fill his imagination for many nights to come as he identified with the adventurer and almost felt the thrill of being devoured (and escaped just in time with some daredevil feat). This episode is linked to another story taken from a book of Indian folk tales, told to him by Elsa Morante (distinguished novelist, poet, translator, and children’s books writer). This episode forms the “philosophical leitmotiv” of his interviews. The story tells of a rich and educated maharajah who out of pity offers himself to two starving tiger cubs … Pasolini almost certainly sensed the continuity and the mirror image connection between the two stories”.

The fact that Pasolini retrospectives have served as one of the high points this year of the 53rd International Film Festival of India in Goa, or the 28th Kolkata International Film Festival, attests to the continuing interest of many film-lovers in the life and legacy of the martyred Italian master. In this connection, the recent upsurge of enthusiasm in Italy for fascist politics and the deathly cult of Mussolini appear to have caused many right-minded, progressive film-lovers the world over to turn with renewed interest to Pasolini’s oeuvre expressing his non-doctrinaire views on Marxism; or his seemingly controversial but actually creative approach to religious faith. As far as Pasolini was concerned, Marx ought not to be degraded into an object of deification, a line which one daresay would have been wholeheartedly supported by Marx himself. Again, Christ was not the son of a non-existent god, but a good and simple figure of blood and bones who set a grand example of struggle and sacrifice for his fellows. Naturally, such a rare, scandalous artist had to be done away with by any means available to the merchants of death.

Vidyarthy Chatterjee writes on cinema,society, and politics.

(Written in December 2022)