Rabindranath Tagore’s Lyrical Ballad on Freedom and Confinement

[Here is a recent performance of this ballad by Lopamudra Mitra and Iman from YouTube:

The caged bird was in the gilded cage, the free bird in the wood

Perchance, once, the twain met each other, perhaps a quirk in the Maker’s mood.

Said the free bird, “Caged bird, dear, come to the woodland let us fly.”

The caged bird replied, “Free bird, dear, join me in the cozy cage, you can if you try.”

Said the free bird, “Nay, I shall never accept any bonds or chains.”

The caged bird bemoaned, “Alas, how shall I brave the woodland’s wild trails.”

The free bird, perched outside, sings woodland songs galore

The caged bird sings the parrot-vocabulary, different their language and lore.

Said the free bird, “Caged bird, dear, let me hear you sing a woodland song.”

The caged bird replied, “Free bird, dear, come learn my cage songs, short and long.”

Said the free bird, “Nay, parrot-songs, still and rote, I want not.”

The caged bird bemoaned, “Alas, how shall I sing woodland songs freedom wrought.”

Said the free bird, “Yonder sky is deep blue and limitless, nowhere any barricade.”

The caged bird replied, “My cage is so tidy and sheltering, barriers nicely laid.”

Said the caged bird, “Let yourself go free entirely in the world of the cloud.”

The caged bird replied, “Secure in my cage’s safe corner, tie yourself and be proud.”

Said the free bird, “Nay, where in the cage would I unfurl my wings?

The caged bird bemoaned, “Alas, in the cloud I find not my perch or the joy it brings.”

And hence the two birds, in love with each other, forever remain apart-

Their beaks meet ‘twixt spaces in the cage’s bars, furtive glances and a broken heart.

Try as they might, neither understands the other, explain their selves in vain-

Lonesome and sad, they flutter their wings and cry, “Come to me, dear, ease my pain!”

Says the free bird, “Never! If they bar the entrance to the cage I will die.”

The caged bird bemoans, “Alas, I have not the strength to fly.”

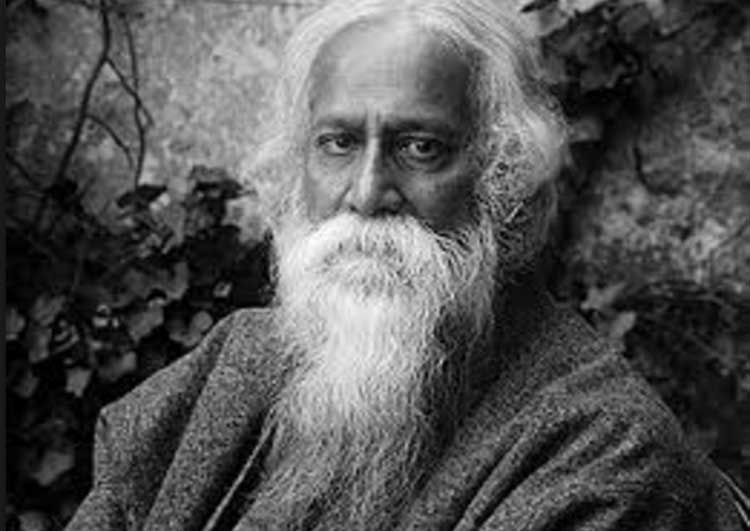

[Commentary: Rabindranath Tagore wrote a number of balladic poems addressing numerous social and philosophical issues relating to human society and existential dilemmas. They are invariably deeply reflective, and brilliantly crafted- in the Bengali language they are simply unmatched and can never be equaled for their lyrical beauty, and are transcendently uplifting for their inner message. In many cases, as in this balladic interchange between two metaphorical birds, Tagore, who often delighted in both bondage and freedom (“Deliverance is not for me in renunciation; I feel the embrace of freedom in a thousand bonds of delight.”)- always in the metaphorical sense, since he felt deeply bonded to the earth, its inhabitants, and also his motherland and his own oppressed people, yet his entire philosophy of life revolved around freedom, of which he wrote copiously. For him, freedom is often best epitomized by the free bird, soaring to great heights in an unbounded sky.

The most curious aspect of Tagore’s take on issues which are conflicted is that he is not invariably unipolar in his outlook (except for those matters which in his mind are ethically and humanistically indefensible). Thus, even in the inherently polarizing issue (at least from the social context) of freedom versus bondage, Tagore takes a sympathetic view of the caged bird, and in this balladic composition, which has received much attention worldwide since Tagore’s boom years following the Nobel Prize (1913), he offers points and counterpoints on behalf of both the free bird and the caged bird. While his personal inclination is (in a subtle way) towards the free bird, he absolutely does not hold the caged bird in contempt.

The above equanimity on matters of polarizing perspectives is very characteristic of Tagore, whose poetic sensibility enabled him to see all issues from different planes of observation. It must be pointed out here that this particular balladic poem was written relatively early in Tagore’s literary career (1892), when he was 31 (incidentally, this was a year before his contemporary luminary of the Bengal Renaissance, Swami Vivekananda, had acquired worldwide acclaim as the messenger for the Universal message of Hinduism, following the 1893 Chicago World Parliament of Religions). And notably, long before his own worldwide acclaim post-1913, Tagore was already both vocal and far-sighted on critical social issues. Here, for instance, is a sampling on his views pertinent to The Caged Bird and the Free Bird from 1894:

“….… There is an independently moving masculine entity within our nature, which is intolerant to bondage alongside a feminine one which prefers to be enclosed and secured within the walls of the home. Both of them remain united in an inseparable fashion. One is eager to develop significantly his undying strength in a diverse way by savo(u)ring ever-new tastes of life, exploring ever-new realms and manifestations and the other remains encircled within innumerable prejudices and traditional practices, enthralled with her habitual deliberations. One takes you out into the vast expanse and the other seems to pull towards home. One is a forest bird and the other is a caged bird. This forest bird is the one that sings much. Although, its song expresses with its diverse melodies the whimper and its craving for unrestricted freedom….” Tagore, Adhunik Sahitya (1894).

Prior to reading Tagore’s views as quoted above, this translator himself felt from a reading of the ballad that the tone of the poem, while not overtly identifying the genders of the two birds, somehow the Free Bird was based on a masculine interpretation, while the Caged Bird was feminine. Tagore’s personal views confirm this instinct, and in this translator’s view, probably offer a better summary of the conflict than anything he (the translator) may offer. Tagore’s Caged Bird is closely allied with the role of womanhood (definitely from Tagore’s time in the late 1800s, and to a certain degree, even today) in society. Women are seen in society (and also taught accordingly) as home-builders and home-makers (the latter word being even more prevalent today in especially conservative circles)- which are rooted upon the ideas of shelters and “safe corners.” Men are the seekers, the adventurers, the ones in the wilderness. Thus, the freedom to be wild and unfettered is a very masculine impulse; the seeking of shelter and wishing to be tied to a safe corner is very feminine. In some ways, these are worlds of opposites, and yet society must draw a line of equilibrium between them.

Well beyond 100 years since Tagore wrote this ballad, the polar planes of femininity and masculinity are still very much in conflict, and sometimes the prevailing politics manipulates these to (in this translator’s view) further subjugate womanhood (which Tagore believed, and MRC agrees, is definitely the gentler of the genders, and is hence prone to exploitation).

Tagore’s Caged Bird feels safe in the security of the cage, the traditions of memorized songs and ideas, the stationarity of stability. His Free Bird, by contrast, likes the boundlessness of the sky, the spontaneity of his woodland songs, the freedom to spread his wings for the unknown. This is a timeless dichotomy, and both preferences have their place in the play of life. This translator maintains that Tagore ultimately aligns himself with the freedom principle, but does not entirely discount the validity of boundaries and security. The human spirit forever seeks to find a balance between these two.

In the modern context, the embedded psychological divergences within the masculine and the feminine gets even more stratified when intermediate gender identities (usually disregarded or overlooked in conventional history, until very recent years) are mixed in.

Beyond the ballad’s relationship with gender identities, it also offers insights into fundamental yearnings within the human heart- at the center of which is the desire to be free. In fact, this yearning is not limited to the human universe either. From this perspective, Tagore’s The Caged Bird and the Free Bird provides for a very early conversation relative to human enslavement and human trafficking, and the issues of colonial and racial dominance and exploitation long before, say, the appearance of Maya Angelou’s moving I know why the caged bird sings, or Frantz Fanon’s epochal The Wretched of the Earth. Hence, while the shelter and security which has defined womanhood (influenced by society to a considerable extent, and also their inherently gentle nature) has had its defendants even among their own (Sarat Chandra Chatterjee’s novels highlight this aspect abundantly), it has also historically had them pay severely in terms of freedom and expansion.

Thus, the perennial dichotomy between freedom and boundaries- the one offering the lure of the new and the unknown in a space without boundaries, and the other offering shelter and security in either self-imposed, or in its far worse manifestations, imposed and coercive boundaries, continues unabated long since Tagore’s ballad lyrically laid out the conversation.

Dr. Monish R. Chatterjee, a professor at the University of Dayton who specializes in applied optics, has contributed more than 130 papers to technical conferences, and has published more than 75 papers in archival journals and conference proceedings, in addition to numerous reference articles on science. He has also authored several literary essays and four books of literary translations from his native Bengali into English (Kamalakanta, Profiles in Faith, Balika Badhu, and Seasons of Life). Dr. Chatterjee believes strongly in humanitarian activism for social justice.

Translated by © Monish R Chatterjee 2020

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER