Written by Abhishek Sethi, Suganda Sharma and Kunal Pant

Shanti was 14 years old when she got married. Despite being an income provider for the family, her husband continuously harassed her and her family for dowry. She suffered the abuse for 14 years after which she decided to move out of her marital home with her children. Later, her husband apologized for his behaviour and asked her to come back on the promise to change his behaviour. Convinced, she returned to his home. But to her surprise, he resumed his harassment. One morning on October 10, 2001, threw acid over her. Suffering severe burns on the face and neck, she lost vision in one eye. Acid also dissolved her one earlobe, leaving her deaf in one ear.

Shanti’s story is one of many stories of acid atrocities against women. 19-year-old Haseena Hussain was attacked by her employer Joseph Rodriquez over the rejection of his sexual advances. “You didn’t listen to me…now you see how you will live your life like this.”, said Joseph as he poured a jug full of acid over her. The incident left a deep scar in her memory which troubled her ever after. Like Shanti, Haseena was also visually impaired and suffered physical burns due to the attack.

The use of acid for violence against women (VAW) reflects the fragile ego of perpetrators treading on revenge and hate, deep-seated in patriarchal societies. The nations with the highest recorded levels of acid attacks include Colombia, Uganda, Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal. The South Asian nations are particularly notorious for disproportionate attacks against women. In India, 70-85% of reported acid attack victims are women. Such assaults are predominantly motivated by spurned love or affections, sexual jealousy, hate or revenge, economic or land disputes. Within India, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal are the states with largest number of attacks, as per NCRB data.

Roots of patriarchy

However, acid attacks represent the face of gender discrimination and inequality in society. Fixed gender-based norms relegating women to positions subordinate to men, reduce women’s power in decision making. Such norms are based on biological determinism where women are vulnerable and “naturally” dependent on men. Another source is the sexual division of labour which has emphasized women’s role in childbearing. Studies say that men create social institutions to bolster their egos and validate their sense of worth. Marriage and property rights are some examples of such patrilocal (marriage being located around the husband’s family) and patrilineal (inheritance and succession through males) institutions. The idea that burning the face will result in loss of honour for women reeks of gendered bias and orthodox thoughts.

When women transgress those norms, like exercising decision making in rejecting love or marriage proposals (to which 78% of cases are attributed), the perpetrators feel entitled to punish them. In order to settle their scores, they aim for disfiguring the face to destroy their victim’s self-confidence, as a public demonstration of their grievances and the grave consequences of their victim’s errors.

While the roots of this ‘wave of vitriolage’ can be traced to patriarchy, the role of means cannot be underestimated. Acid (sulphuric acid, nitric acid, or hydrochloric acid) is cheap and easily available – even in the most rural parts of India – from motor mechanics, repair shops, and jewellers. People in villages generally use acid as a toilet cleaner which can be obtained for less than Rs. 25 per litre. Such over the counter availability of a potent weapon makes it easy to abuse by perpetrators. Asha Mukherjee of Acid Survivors Foundation of India says, “In India, acid has two uses – on women and in the bathroom.”.

Legislations aren’t enough

After a petition by Laxmi Agarwal petitioned in 2013, the Supreme Court directed that every state and union territory shall issue licenses to the retailers selling acid. Moreover, the shops are completely prohibited to sell the chemical under the Poisons Act, unless they keep up-to-date records of the sale, including the photo identity, address of the buyer, and quantity sold along with the reason for the purchase. Today, observations show that the regulations are scarcely followed. Acid is still sold openly in various states. The ‘Shoot Acid’ campaign, led by Laxmi, revealed widespread non-compliance to the guidelines. As Asha enquired about ‘tezaab’ to a local store in Delhi, the shopkeeper asked her how many bottles she needed. This highlights the need for stricter enforcement of the rules, including but not limited to surprise checks from time to time.

2: Open sale of acid in various states

After the Nirbhaya case, the parliament approved The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 which put in force major amendments in the Indian Penal Code, recognizing for the first-time acid attack as a separate offense under the Code. It was a welcome move by the government; a positive step towards acknowledging the plight of victims. Section 326A provides for a minimum of 10 years of jail for causing grievous hurt by throwing acid. However, the convictions under the law have been extremely low. For instance, according to NCRB data, out of the 228 fresh recorded cases in 2018, there was conviction in only one case. The slow rate of conviction means that the cases keep piling up in courts. Therefore, in 2018, a total of 523 cases were slated for trial, including cases that were pending from previous years. According to data released by NCRB, in 5 years (from 2014 to 2018), India witnessed 1483 cases of acid attack incidents. This figure is highly likely to be underreported as States like Bihar and U.P have lower rates of reported crimes against women. Adding onto the pain that survivors go through, police, judges, and authorities are insensitive towards them. Delay in filing charge sheets, misplacing documents, and passing insensitive comments are some of the examples of mishandling of grievances of people surviving the barbaric acts.

The financial burden and irregular compensations

Besides physical and psychological consequences, the acid attacks pose a huge financial burden on victims and their families. Acid attack victims need a different kind of first aid than ordinary burn victims. Many are turned away from hospitals because they cannot afford the treatment. Even if they are admitted, a lot of hospitals don’t have the know-how to treat them. In numerous cases, the victims have died because they couldn’t access, afford, or received proper care. Revisiting Haseena’s story, medical treatment was a long and expensive traverse for her. She underwent 35 surgeries and spent more than Rs.20 lakh, sacrificing her house, jewellery, and savings from her job. The incident drastically worsened her socio-economic condition. It is telling that when the Supreme Court for the first time awarded her the highest compensation till the date of Rs. 3 lakhs, it did little to improve her position.

Today, the victims are entitled to compensation under various schemes. Some of them are NALSA’s Compensation Scheme for Women Victims/Survivors of Sexual Assault/Other Crimes-2018, Victim Compensation Fund, and Nirbhaya Fund. Additional compensation of Rs.1 lakh is provided under Prime Minister Relief Fund. The government has set up state and district level legal service authorities (SLSA and DLSA) to provide legal aid to the beneficiaries and determine the amount of compensation. For example, NALSA’s scheme provides compensation ranging from INR 3 to 8 lakh depending on the severity of the case. There are some flaws in the scheme. First, the determination of compensation to victims is not fool-proof and is biased. In one case, a woman appealed against a high court judge who believed her story “does not ring true”, and hence “no compensation is required to be paid.” Secondly, there is a delay in the dispensation of relief. The National Commission for Women (NCW) recently highlighted that the compensation under NALSA has not been paid to 799 out of 1273 cases. The commission in their monthly newsletter suggested that some states/UTs have not provided adequate and timely medical treatment/assistance to survivors of acid attacks. Above all, the victims get compensated (however insufficiently) only for physical sufferings, while their mental harassment and the social stigma they may face throughout their life are largely ignored.

The dent of discriminatory stare

Society presents the biggest hurdle for the survivors. They are ostracized and discriminated against in every aspect, including finding suitable jobs or marriage prospects. The lack of employment opportunities results in increasing dependencies which further leads to abandonment, sometimes even from families. Laxmi Agarwal, the Chhapaak girl, mentioned in an interview that the people, especially women, used to taunt her, call her names and smear her and her family. The rebukes were so strong that she once contemplated suicide. It is not surprising that in India, where various forms of VAW like domestic violence and dowry deaths are prevalent, the social exclusion of acid attack victims will be widespread.

A ray of hope: the role of citizen entrepreneurship

In a society that dispirits and disheartens souls at times, some people act as a ray of hope and prove that all is not lost.

Alok Dixit, the founder of Chhanv Foundation, has been engaged with the acid attack issue since 2013. He organized the Stop Acid Attacks campaign, mobilizing the survivors and their families to demand justice from the government and judiciary. Before 2013, acid attacks were considered similar to pickpocket cases with the accused getting a 3 months jail with easy bail. Moreover, there was no attempt on monitoring the cases till 2013. All this has changed with the dedicated and unflinching efforts of the campaigners of the Stop Acid Attack movement. It is only due to their successful campaigning and advocacy that the government and judiciary recognized the heinous crime of acid attacks and made significant amendments to the law including imprisonment and compensation. In 2013, the National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) started providing the number of attacks happening in the country. However, the activists knew that mere legislation won’t work for the upliftment of victims.

Alok Dixit, the founder of Chhanv Foundation, has been engaged with the acid attack issue since 2013. He organized the Stop Acid Attacks campaign, mobilizing the survivors and their families to demand justice from the government and judiciary. Before 2013, acid attacks were considered similar to pickpocket cases with the accused getting a 3 months jail with easy bail. Moreover, there was no attempt on monitoring the cases till 2013. All this has changed with the dedicated and unflinching efforts of the campaigners of the Stop Acid Attack movement. It is only due to their successful campaigning and advocacy that the government and judiciary recognized the heinous crime of acid attacks and made significant amendments to the law including imprisonment and compensation. In 2013, the National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) started providing the number of attacks happening in the country. However, the activists knew that mere legislation won’t work for the upliftment of victims.

At a time when Alok was exploring the fields of journalism and media, he got deeper into the issue of acid attacks and started campaigning against it. Alok and Chhanv foundation have redefined rehabilitation by providing medical assistance, legal advisory, educational support, and employment opportunities. Till today, Chhanv Foundation has benefitted more than 100 acid attack survivors in their medical, compensation, legal & employment.

Sheroes Hangout, a café run by acid attack survivors was launched in 2014 in the city of Taj, Agra. It is an excellent initiative by the activist group fighting for the rights of acid attack survivors, led by Alok Dixit. In the café, the staff and the customers from all around the world chat freely and comfortably share their feelings including the most vulnerable moments in their lives. What initially started as a crowdfunded project, with a ‘pay as you go’ policy and supported by patrons, is now a sustainable business model, with fixed menu and prices, like any other café, yet unlike them all. The café has become an important source of income and helped the staff become more emotionally and financially secure. Sheroes has also expanded by opening a new café in Lucknow. Recently, the acid attack survivors launched a new business venture, “A Gift Story”, an online shop store. It is another compelling story of incorporating entrepreneurship in social activism and support systems.

Learnings from Bangladesh: A nation that combated acid violence

Like India, Bangladesh had a horrible chapter of acid violence, facing around 300 cases every year. The attacks were characterized by similar reasons as other Asian nations. However, the country, the citizens, and NGOs (special mention to Naripokkho and Acid Survivors Foundation) produced joint efforts to combat the brutal violence. They followed a five-pronged strategy: public awareness, case reporting, short-term treatment, long-term treatment, and legal justice. The punishment is usually commensurate with the extent of injuries sustained by the victim and is usually a life sentence since it is considered a premeditated crime. In 2002, the parliament brought in special laws, with a provision of a death sentence. The NGOs have played a huge role in spreading awareness about the issues, spurring the creation of much-needed legislation. One such critical legislation was the Acid Control Act, 2002. The act made punishable the unlicensed production, storage, sale, and use of acid with a prison sentence of 3 to 10 years. Compare it with India, a petty fine of Rs. 50,000 is enough to get away with the law.

In addition to the community outreach and stricter regulation, the government had focused on providing healthcare services to survivors, establishing a burn unit, and employing plastic surgeons to treat victims in a speedy manner. Such medical care is also complemented by care facilities provided by ASF. As a result of all the efforts, Bangladesh has reduced the number of the reported attacks from 300 to around 150 cases as of 2010.

In India, similarly the initiatives like Chhanv, Campaign and Struggle against Acid Attacks on Women (CSAAAW), Acid Survivors Foundation, Make Love Not Scars, and Meer Foundation are taking an active part in citizen entrepreneurship engaging in policymaking, activism, and sustainable solution-oriented actionable approach, making the otherwise difficult lives of survivors easier. However, much work is needed to be done on the government side, especially with the recent compensation delays, low conviction rates, police insensitivity, and flouting of guidelines coming to highlight.

Covid-19 and the struggle for survivors

The coronavirus pandemic has altered societies in an unprecedented manner. It has disproportionately affected vulnerable groups like migrants and minorities. It has posed a similar challenge to the acid attack survivors, who were fighting and managing their lives. Sheroes Hangout Café in Agra is struggling due to lower footfall during the pandemic. Being income support for more than 30 survivors, it is the means for improving their financial standing and living suitable lives. Many hospitals have stopped regular services and are running only emergency departments, depriving the survivors who need immediate medical attention, increasing the chances of developing infections.

In the light of the above challenges, Chhanv Foundation has set up a COVID-19 Corpus Fund for helping the survivors deal with the struggles during the pandemic. For this, they are inviting individual donations, Government grants, CSR tie-ups, NGOs, and charitable organizations. The online fundraising campaign (bit.ly/chhancvmedicalsupport) aims to provide much-needed medical support. To demand support from the government, the foundation has launched a petition #INDIA IS ABLED (http://bit.do/IndiaIsAbled).

Make Love not Scars: Recognizing genuine efforts and focusing on awareness and sensitivity

On the occasion of Human Rights Day (December 10), Chhanv Foundation won the Helen Keller Award 2020 for promoting employment opportunities for persons with disabilities. Alok Dixit says “The survivors have to be educated and employed while they fight for justice. This would help them get back all of those things that they might have lost during and post the attack.” But at the heart of the issue lies the potential impact of a more aware and sensitive society. “Acid violence and the disability followed after is not discussed in the public circles and hence, not known to everybody. Thus, we should spread awareness regarding this”, says Alok.

For the survivors, one of the most torturous experiences is to recall the incident that attempted to scar their lives. In a documentary titled Black Roses and Red Dresses, Laxmi recalls “Every time I think of his name, I start reliving the attack. That’s why I never say his name. I see him right there pouring acid on me. My heart sinks.” The feeling cannot be imagined but certainly can be felt.

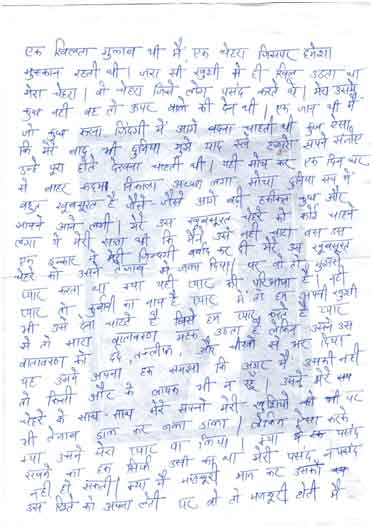

The Black Rose Campaign is a very heartful movement that was started by the Stop Acid Attacks activists, with the aim of spreading the message of ‘peaceful disagreement’ instead of letting our burning hatred and anguish take over the better of us. This is what the Black Rose Campaign teaches our society, which has become violent and impatient as years proceed. For the survivors, it is an emotional expression of their memories – “By writing letters to your attacker, you can express what you feel.”

4: A Letter to her attacker from Acid Attack Survivor – Shaheen

Written by Abhishek Sethi, Suganda Sharma and Kunal Pant (Second-year students at IIM Ahmedabad. We believe in gender equality and development, and support the fight against Violence against Women. Our petition to support Acid attack victims: https://www.change.org/AcidAttacksIssue)

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER