“The U.S. government should end its prosecution of Julian Assange for publishing secrets,” the editors of the Times, the Guardian, Le Monde, Der Spiegel and El Pais wrote in a joint letter published Monday.

The letter was signed by Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger and the editors and publishers of the Guardian (Britain), Le Monde (France), Der Spiegel (Germany) and El Pais (Spain).

In a joint letter, the news organizations warned that the indictment of Julian Assange “sets a dangerous precedent” that could chill reporting about matters of national security.

“Obtaining and disclosing sensitive information when necessary in the public interest is a core part of the daily work of journalists,” the letter said. “If that work is criminalized, our public discourse and our democracies are made significantly weaker.”

“Holding governments accountable is part of the core mission of a free press in a democracy,” the letter said.

Reports by The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian and others said:

The New York Times and four leading European news organizations called on the U.S. Justice Department to drop criminal charges against WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, warning in an open letter Monday that the case could criminalize U.S. journalists’ work exposing government secrets and potential wrongdoing.

The news organizations acknowledged that they had been critical of Assange for releasing unredacted information in the past, and some were concerned by allegations in a federal indictment that Assange “attempted to aid in computer intrusion of a classified database.” Professional news organizations forbid reporters from gathering information through unethical or illegal means.

But much of Assange’s indictment focuses on his 2010 and 2011 disclosure of thousands of pages of classified military records and diplomatic cables about the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, which had been shared by former Army private Chelsea Manning.

The news organizations said that they partnered with Assange more than a decade ago to reveal “corruption, diplomatic scandals and spy affairs on an international scale,” and that the trove of records he made available is still being mined by journalists and historians.

“This indictment sets a dangerous precedent, and threatens to undermine America’s First Amendment and the freedom of the press,” they wrote.

Assange, who is currently detained in a London prison as he appeals an order from the British government extraditing him to the U.S., says he is the target of a political prosecution and that the U.S. prison system would not treat him humanely.

Mr. Assange, who has been fighting extradition from Britain since his arrest there in 2019, is also accused of participating in a hacking-related conspiracy.

The letter notably did not urge the U.S. Justice Department to drop that aspect of the case, though it said that “some of us are concerned” about it, too.

The U.S. Justice Department refrained from prosecuting Assange under President Barack Obama. After President Donald Trump took office, the Justice Department asked federal prosecutors in Virginia to revisit the case. They ultimately obtained an 18-count indictment charging the WikiLeaks founder with a hacking conspiracy and disclosure of national defense information, which officials say put lives in danger.

The reports said:

The indictment has stirred controversy inside the Justice Department. Prosecutors filed some of the charges under the Espionage Act of 1917, a World War I-era law that had been used to charge spies or officials leaking information from inside the government, but never publishers or broadcasters.

Two federal prosecutors in Virginia who were involved in the Assange case argued against bringing charges under the Espionage Act, concerned that, among other things, it posed risks to First Amendment protections.

The U.S. Justice Department officials declined to comment on the open letter Monday.

Times spokeswoman Danielle Rhoades Ha said Sulzberger signed the letter in consultation with the company’s legal department. “No editors were involved,” she said. Danielle Rhoades Ha said the newsroom was not involved.

The Washington Post also published news articles about some of the documents Assange unearthed. In 2019, Martin Baron, then the executive editor of The Post, criticized the Assange indictment: “Dating as far back as the Pentagon papers case and beyond, journalists have been receiving and reporting on information that the government deemed classified. Wrongdoing and abuse of power were exposed. With the new indictment of Julian Assange, the government is advancing a legal argument that places such important work in jeopardy and undermines the very purpose of the First Amendment.”

A spokeswoman for The Washington Post pointed to Baron’s statement on Monday and declined to comment further.

Barry Pollack, a U.S.-based lawyer for Assange, said: “Media organizations in the U.S. and abroad are right to express their concern about the criminal charges brought against Mr. Assange and the extraordinary threat to First Amendment values presented by the U.S. prosecution and extradition request.”

The reports said:

The case against Mr. Assange is complicated and does not turn on the question of whether he is considered a journalist, but rather on whether his journalistic-style activities of soliciting and publishing classified information can or should be treated as a crime.

The letter comes as U.S. Attorney General Merrick B. Garland has sought to rein in ways in which the Justice Department has made it harder for journalists to do their jobs. In October, he issued new regulations that ban the use of subpoenas, warrants or court orders to seize reporters’ communications records or demand their notes or testimony in an effort to uncover confidential sources in leak investigations.

Mr. Assange and WikiLeaks catapulted to global fame in 2010 when he began publishing classified videos and documents related to the United States’ wars and its foreign relations.

It eventually became clear that Chelsea Manning, a former Army intelligence analyst, had provided the archives to WikiLeaks. She was sentenced to 35 years in prison after a court-martial trial in 2013. President Barack Obama commuted most of her remaining sentence shortly before leaving office in January 2017.

Ms. Manning’s disclosures amounted to one of the most extraordinary leaks in American history. They included about 250,000 State Department cables that revealed many secret things around the world, dossiers about Guantánamo Bay detainees being held without trial and logs of significant events in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars that divulged, among other things, that civilian casualties were higher than official estimates.

The news organizations’ letter noted that the same five institutions had publicly criticized Mr. Assange in 2011 when unredacted copies of the cables were released, revealing the names of people in dangerous countries who had helped the United States and putting their lives at risk. At Ms. Manning’s trial, prosecutors did not say anyone had been killed as a result, but officials have said the government spent significant resources in getting such people out of danger.

While the Obama administration and career law enforcement and national security officials disliked Mr. Assange, transparency advocates and antiwar activists treated him as an icon.

His public image shifted significantly after WikiLeaks published Democratic emails. But the criminal case against him is not about the Democratic emails.

The open letter notes that the Obama administration had weighed charging Mr. Assange in connection with the Manning leaks but did not do so — in part because there was no clear way to legally distinguish WikiLeaks’ actions from those of traditional news organizations like The Times that write about national security matters.

But in March 2018, under the Trump administration, the Justice Department obtained a sealed grand jury indictment against Mr. Assange. Initially, the charges sidestepped issues of press freedom, narrowly accusing him of a hacking-related offense by offering to help Ms. Manning mask her tracks on a secure computer network.

Under Attorney General William P. Barr, the department later escalated the case by obtaining an additional indictment that included a second set of allegations: that his journalistic-style activities violated the Espionage Act, a World War I-era law that makes the unauthorized retention and dissemination of national security secrets a crime.

Another indictment expanded the allegations attached to the hacking-related charge, to include a broader WikiLeaks effort to encourage hackers to obtain secret material and provide it to the group.

There is no precedent in the U.S. for prosecuting a publisher of information — as opposed to a spy or a government official who leaked secrets — under the Espionage Act. The Trump administration’s decision to bring such charges against Mr. Assange raised novel and profound questions about the meaning of the First Amendment.

For now, those issues have not been tested in court because the case is paused while Mr. Assange fights extradition. But the open letter called on the Justice Department to drop the Espionage Act charges.

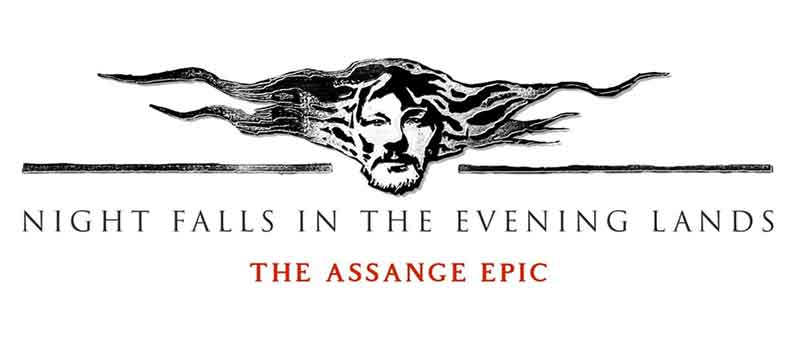

The Open Letter: Publishing is Not a Crime

Following is the open letter (https://www.nytco.com/press/an-open-letter-from-editors-and-publishers-publishing-is-not-a-crime/):

Twelve years ago, on November 28th 2010, our five international media outlets – The New York Times, the Guardian, Le Monde, El Pais and DER SPIEGEL – published a series of revelations in cooperation with Wikileaks that made the headlines around the globe.

“Cable gate”, a set of 251,000 confidential cables from the US State Department disclosed corruption, diplomatic scandals and spy affairs on an international scale.

In the words of The New York Times, the documents told “the unvarnished story of how the government makes its biggest decisions, the decisions that cost the country most heavily in lives and money”. Even now in 2022, journalists and historians continue to publish new revelations, using the unique trove of documents.

For Julian Assange, publisher of Wikileaks, the publication of “Cable gate” and several other related leaks had the most severe consequences. On April 12th, 2019, Assange was arrested in London on a US arrest warrant, and has now been held for three and a half years in a high security British prison usually used for terrorists and members of organized crime groups. He faces extradition to the US and a sentence of up to 175 years in an American maximum security prison.

This group of editors and publishers, all of whom had worked with Assange, felt the need to publicly criticize his conduct in 2011 when unredacted copies of the cables were released, and some of us are concerned about the allegations in the indictment that he attempted to aid in computer intrusion of a classified database. But we come together now to express our grave concerns about the continued prosecution of Julian Assange for obtaining and publishing classified materials.

The Obama-Biden Administration, in office during the Wikileaks publication in 2010, refrained from indicting Assange, explaining that they would have had to indict journalists from major news outlets too. Their position placed a premium on press freedom, despite its uncomfortable consequences. Under Donald Trump however, the position changed. The DOJ relied on an old law, the Espionage Act of 1917 (designed to prosecute potential spies during World War 1), which has never been used to prosecute a publisher or broadcaster.

This indictment sets a dangerous precedent, and threatens to undermine America’s First Amendment and the freedom of the press.

Holding governments accountable is part of the core mission of a free press in a democracy.

Obtaining and disclosing sensitive information when necessary in the public interest is a core part of the daily work of journalists. If that work is criminalised, our public discourse and our democracies are made significantly weaker.

Twelve years after the publication of “Cable gate”, it is time for the U.S. government to end its prosecution of Julian Assange for publishing secrets.

Publishing is not a crime.

The editors and publishers of:

-

- The New York Times

- The Guardian

- Le Monde

- DER SPIEGEL

- El Pais