About 3.2 million Americans have moved due to the mounting risk of flooding, the First Street Foundation (FSF), a nonprofit research group, said in a report that focuses on so-called “climate abandonment areas,” or locations where the local population fell between 2000 and 2020 because of risks linked to climate change.

Many of those areas are in parts of the U.S. that also have seen a surge of migration during the past two decades, including Sun Belt states such as Florida and Texas. Such communities risk an economic downward spiral as population loss causes a decline in property values and local services, the group found.

“There appears to be clear winners and losers in regard to the impact of flood risk on neighborhood level population change,” Jeremy Porter, head of climate implications research at the FSF, said in a statement.

He added, “The downstream implications of this are massive and impact property values, neighborhood composition, and commercial viability both positively and negatively.”

Fastest-Growing Metro Areas

Climate abandonment areas exist across the U.S., even in some of the country’s fastest-growing metro areas, according to another study – Integrating climate change induced flood risk into future population projections (Shu, E.G., Porter, J.R., Hauer, M.E. et al. Integrating climate change induced flood risk into future population projections. Nat Commun 14, 7870 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43493-8), which was published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications. The scientists have integrated data on flood exposure and population with a series of indicators related to local political, social, and economic conditions.

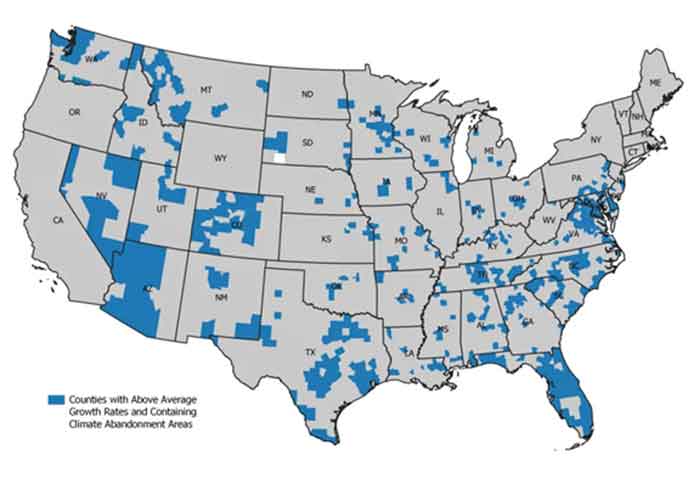

About 513 counties in the U.S. saw their populations grow at a faster-than-average pace during the last two decades, yet they also included neighborhoods that lost population in areas of high flooding risk, the analysis found.

Areas in blue show the counties that saw population growth, while also containing Most of those areas are concentrated in three regions: Gulf Coast of Texas, Mid-Atlantic region between Washington, D.C., and New Jersey, most of coastal Florida

The most affected municipality is Bexar County in Texas, which includes San Antonio. Between 2000 and 2020, the county added more than 644,000 new residents, yet still lost population in about 17% of its Census blocks, according to FSF. (In urban areas in the U.S., Census blocks are smaller areas that resemble city blocks, although in rural areas they can be quite large and be defined by natural features like rivers.)

Other counties with the largest share of population migration due to flooding risk include Will County, Illinois, and El Paso County in Texas, the study found.

Midwest Could Be Hard-hit

The analysis also examines which regions of the U.S. could face climate migration in the coming decades, and, perhaps surprisingly, Midwestern states including Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Ohio face some of the highest risks, the study found.

Extreme weather in the form of increased flooding and massive wildfires is particularly affecting people’s homes. Across the U.S., nearly 36 million properties — one-quarter of all U.S. real estate — face rising insurance prices and reduced coverage due to high climate risks, First Street found in an earlier analysis this year.

Rising risk of floods is hollowing out counties across the United States — creating abandoned pockets in the hearts of cities, a new report has found.

These abandoned areas tend to map onto regions of historic disinvestment — and flight out of them is accelerating, according to findings published in Nature Climate Change.

In cities across the country, but particularly concentrated in the Midwestern states such as Indiana, Ohio, Michigan and Minnesota, increasing flood risk has driven this “climate abandonment” of individual census tracts, sometimes quite rapidly.

That is the kind of dynamic demographers fear could lead to a “doom loop” of accelerating outmigration, until only those who cannot afford to leave are left behind in areas most threatened by the changing climate.

And it could lead to a mass migration of historic proportions, the study found. If investments are not made to adapt these areas to better withstand environmental dangers, “there are likely to be large migrations on a similar scale to the Great Migration in the twentieth century, during which 4 million people may have moved,” the authors wrote.

Among the areas people are abandoning in the face of rising flood risks are particular neighborhoods in many cities — such as Houston, Miami and Washington, D.C. — that are rapidly growing overall.

But while those cities are still pulling people in faster than flood risk pushes them out, the study indicates many are heading toward a tipping point after which a process of decline will begin.

The research into the impacts of flood risk on migration comes courtesy of FSF. The FSF makes long-term predictions of climate risk for individual properties across the U.S.

The data shows that climate change is no longer “a thing that might impact my kids,” Eby said. “It is changing the valuation on my property right now.”

The success of the tools FSF created to track those risks left its team with a paradox, said Jeremy Porter, FSF’s head of climate implications and a professor at the City University of New York.

One pervasive narrative of American response to climate change is that people “are moving toward risk,” Porter said, as they leave the Midwest and Northeast for the heat- and flood-prone Sunbelt and the fire-prone West.

In terms of flood, Porter said FSF’s research has borne that narrative out — at least when it comes to interstate moves.

But as FSF tools were integrated into real estate sites Redfin and Zillow, it became clear that people were in fact taking climate into account in deciding where to buy, Porter said.

And those long-distance moves are only a small part of the story, because most moves are local. About four times as many Americans move within their county as move across state lines, Porter told.

By looking at the impacts of rising flood risk on the population of about 8 million individual census blocks — slices of neighborhoods which often hold just a few dozen people — Porter’s team found that when it comes to the more prevalent short-term moves, people generally move away from flood risk, not toward it.

These findings make up just a small part of the broader picture of climate risk. (The FSF is releasing a more expansive model to track the impact of all climate risks on migration — including heat, fire, smoke and wind — early next year.)

But they show that flood risk alone is already driving outmigration from about 3 million census blocks across the country, which are home to about a third of the nation’s population.

Over the past 20 years, those blocks have lost about 9 million people, according to the study — about 3 million of them as a result of rising risk from floods.

This kind of declining neighborhood is what the First Street team call “climate abandonment areas” — parts of neighborhoods where more people left between 2000 and 2020 than moved in.

In most cases, this decline is on the order of 10 percent.

But in the most extreme cases — such as Staten Island’s Midland Beach neighborhood — the drop in population was more like a collapse.

In that census block, First Street found that a 2000-era population of 93 people had fallen by two-thirds, to 31 people by 2020.

This sort of dramatic collapse risks triggering a death spiral, Anne Perrault of Public Citizen told.

Hollowed-out Neighborhoods

In many regions, the outmigration is leaving behind hollowed-out neighborhoods, which in the most extreme cases causes abandonment to cascade into more and more abandonment, she explained.

As the spiral accelerates, Perrault said, “migrations will continue to occur from climate vulnerable areas, all while these areas expand because of increased global warming.”

That decline in population and property values in turn makes municipal lending increasingly harder for cities to acquire to fix things up — creating a self-reinforcing pattern of outmigration.

The Financial Stability Oversight Council reiterated concerns about such patterns developing in a Thursday report, which found that planetary heating was “imposing significant costs on the public and the economy, with economic costs from climate change expected to grow.”

Insurance Companies

That report emphasized the spreading danger of doom loops across the country, in particular as insurance companies withdraw from areas facing climate risks, leading to a cycle of declining home values, leading to fewer new loans being made to buy, build or fix up local houses.

The neighborhoods currently losing people are just one part of a developing story of loss and growth. The Nature study identified 513 counties — or nearly 20 percent of the continental U.S. — that were growing faster than the national average but contained these blocks being abandoned.

While the population is rising in many of these flood-prone counties, people are moving in more slowly than they are to comparable areas without flood risk: Such neighborhoods are attracting about 4 million fewer people than equivalent ones that aren’t facing that risk, the study found.

These areas are scattered across the U.S., but they are particularly concentrated in the Gulf Coast (particularly Houston and virtually all of Florida) and the mid-Atlantic between New Jersey and Washington, D.C.

For example, metro areas including Houston, Fort Worth, El Paso and Phoenix, and the Jersey Shore, all saw growth of 20 to 40 percent between 2000 and 2040 — while 10 to 20 percent of the census tracts in those counties lost people, according to the Nature study.

The FSF model predicts that as a group, these areas of heightened growth and rising risk will hit a tipping point beginning in 2025 — after which point they will begin to decline, ultimately losing an estimated 5 million people from flood risk alone.

Over the next 30 years, the model predicts that these new “climate abandonment areas” will continue to spread — and be joined by nearly half a million more such declining neighborhoods.

By 2053, many of the most-populated counties in the country will see between 20 percent and more than 50 percent of their territory in decline, according to the model.

It projects that about 55 percent of the counties that make up Minneapolis, for example, will be losing people by midcentury, followed by about 45 percent of Milwaukee County, 30 percent of Providence County, R.I., and a quarter of the D.C. suburb of Alexandria, Va.

By contrast, the model predicts that some urban counties will see increased migration due to falling risk, such as counties in the metro regions that hold Newark, N.J.; Detroit; Boulder, Colo.; San Francisco; and Chicago.

The FSF data also revealed a troubling trend for cities as a whole. While migration to newer, less flood-prone developments lowered flood risk for individuals, the data shows it likely raises that risk for cites overall.

Take San Antonio, Texas — a fast growing metropolis where First Street data shows 18 percent of the census blocks have been losing people to flood risk even as the county as a whole has gained 44 percent more people.

In that city, people have been trickling out of the increasingly flood-prone urban core — neighborhoods like Tobin Hill/Pearl, where 40 percent of tracts are losing population — to newer, expanding suburban developments in the hills outside town, according to the data.

While that may lower risk for those people in particular, every new development rising in former scrubland and cattle pasture brings higher flood risk for everyone downstream.

That is because new developments mean vast new swaths of rain-repelling asphalt and concrete on lands that once soaked up rain, Porter told.

The rise in new “roads, homes, and shopping centers would all significantly impact the natural environment and the natural management of precipitation and riverine flooding,” he said.

And the new land cover concentrates and funnels floodwater downhill, toward those who have remained in the central core, he explained.

Porter said the spread of counties declining under flood risk present policymakers with a paradox — but also with some of the information needed to solve it.

Areas in the second category, Porter argued, can be saved by timely investment in public infrastructure.

Without such intervention — and in some areas, even with it — the exodus may become unstoppable, he said.

The end state of this process is a situation where “the people that can afford to leave, leave, and people [who] can’t afford to leave end up staying in the community,” Porter said.

“You end up with a lot of vulnerable populations at risk.”

$2.3 Trillion In Damages Across The U.S.

The study – Integrating climate change induced flood risk into future population projections – said:

Flood exposure has been linked to shifts in population sizes and composition. Traditionally, these changes have been observed at a local level providing insight to local dynamics but not general trends, or at a coarse resolution that does not capture localized shifts. Using historic flood data between 2000-2023 across the Contiguous United States (CONUS), the scientists identify the relationships between flood exposure and population change. They demonstrate that observed declines in population are statistically associated with higher levels of historic flood exposure, which may be subsequently coupled with future population projections. Several locations have already begun to see population responses to observed flood exposure and are forecasted to have decreased future growth rates as a result. Finally, the scientists find that exposure to high frequency flooding (5 and 20-year return periods) results in 2-7% lower growth rates than baseline projections. This is exacerbated in areas with relatively high exposure to frequent flooding where growth is expected to decline over the next 30 years.

The study report said:

Since 1980, there have been over 300 disaster events responsible for $2.3 trillion in damages across the US. Nearly half of these damages can be attributed to flooding and tropical cyclones. As such, understanding the ways that flood risk impacts human systems is of great importance.

Increasing flood exposure and losses are expected to drive population and demographic shifts in the U.S. Some projections estimate that globally, up to 216 million people may migrate due to climate change by 2050.

This existing research has found that areas with high climate risk (or exposure) are currently seeing an influx of population and growing. However, increasing evidence suggests that a more voluntary form of climate migration is associated with flood risk at a more local scale, taking into account property and neighborhood level variations in exposure.

Climate Migration Likely To Increase

Climate migration is likely to increase over time, with projections suggesting between 4.2 and 13.1 million people in the U.S. may be at risk of inundation from sea level rise by 2100, and suggests that in the absence of adaptation there are likely to be large migrations on a similar scale to the Great Migration in the twentieth century, during which 4 million people may have moved. With 21.8 million properties currently having some exposure to flooding within the CONUS, and 23.5 million expected to have flood exposure by the middle of the century, it is important to understand how migration and settlement patterns may change over time.

The study report said:

When climate impacts are evaluated over longer time periods, it is likely that a combination of direct (e.g. property inundation) and indirect (e.g. neighbors moving away) factors will contribute to migration. In addition, these migrations are likely to occur along existing pathways, thus likely constituting an enhanced normal out-migration.

The report said:

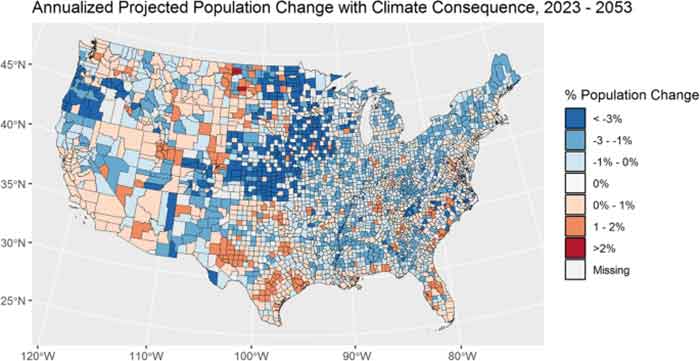

The future population projections indicate that when introducing the climate consequences derived from the modeling process, there are overall negative impacts on population growth in areas with high flood exposure.

Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of the percentage of future population changes that is due to the integration of the modeled climate consequence. The differentiation is interesting to note because, while there is a climate consequence associated with the tipping points identified in this research, there are also larger macro level drivers of population change that are built into the baseline SSP2 trajectory used as the baseline for this forecast. Again, given the highly localized nature of flood risk, the acute impact needed to be explored at a higher resolution.

Fig. 1: County level projected population change resulting from the application of the climate consequence to the SSP2 future population projections.

Population change is shown as an annualized rate, comparing projected future population counts (~2053) to current population counts (~2023). Spatial layers were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau.