Dhawale, A., Sainath, P., Deshpande, S., Prashad, V.(2018). The Kisan Long March in Maharashtra. LeftWord Books.

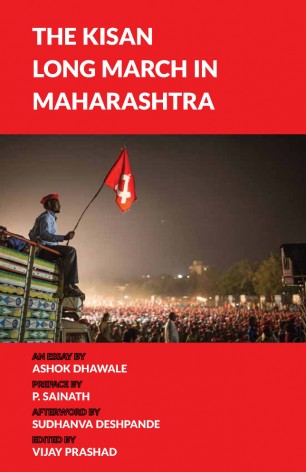

“Land reform is on the agenda of mankind”. So wrote William Hinton over five decades ago, in the preface to his agrarian classic – Fanshen. The events described in The Kisan Long March– 50,000 farmers marching over 200km, in a veritable sea of red – suggest that Hinton’s remark remains as relevant today, as it was in 1966.

But the events described in The Kisan Long March, are not the only remarkable facet of this “small book on a large struggle” (7). The fact that it has been made freely available for download under a Creative Commons license by the publisher – Leftwordbooks – is both admirable, and suggestive of the continued strength of characterwithin the Indian left, contra to thepopular characterization of the India’s left parties as irredeemably corrupt and stiflingly bureaucratized.

But the events described in The Kisan Long March, are not the only remarkable facet of this “small book on a large struggle” (7). The fact that it has been made freely available for download under a Creative Commons license by the publisher – Leftwordbooks – is both admirable, and suggestive of the continued strength of characterwithin the Indian left, contra to thepopular characterization of the India’s left parties as irredeemably corrupt and stiflingly bureaucratized.

Following a preface by the radical historian Vijay Prashad, which situates the Kisan Long March in the context of an ongoing, and increasingly globalized, agrarian crisis, the tale of the 200 km march is told through a series of essays – a concise preface by P. Sainath, a detailed account by Ashok Dhawale, and an up-close anthropology by Sudhanva Deshpande.

Several themes emerge. First, the long history of silent struggle, leading up to the much-publicized Long March. Few outside of India got wind of the 2016 Coffin Rally, where 10,000 people gathered to protest the unprecedented epidemic of farmer suicides in the Indian countryside – three million over the past twenty five years, that’s more than one suicide every five minutes!

Few were aware of theWada Gherao, the 2016 Commissioner’s office occupations, of the 2017 Farmer’s Strike. Yet, as the authors remind us, these were the struggles that laid the groundwork for the long march, and in that sense, the march becomes much more than a sporadic hissy fit, more than a fleeting news item. It becomes the culmination of ongoing, ever-present, struggle, and serves as a reminder to all activiststo keep fighting through the bleak times, because the shining moments of glory, often take years and years to cultivate.

A second theme that runs through the essays presented in The Kisan Long March, is what can best be described using Sudhanva Deshpande’s phrase: “solidarity in action”. While the corporate media complained of rambunctious peasants, demanding handouts from the government, and disrupting traffic in the towns, the villagers of Azad Maidan baked 150,000 bhakrisfor the marchers passing by.

Doctors in Mumbai and elsewhere, set up free medical camps for the beleaguered marchers. Volunteers brought stones to construct makeshift ovens, one police man gave his entire week’s salary to pay for water buckets.

This was “solidarity in action”. The preachers of division could not stop the sons and daughters of farmers in the cities, showing their support for the marching peasants. Urbanites and ruralites came together as one. Peasants and workers of all castes, religions, and creeds came together as one, to oppose the neoliberal steamroller raging through the countryside, and hurling people in all regions into unprecedented precarity.

This is perhaps the greatest lesson that The Kisan Long March has to share with the world –In India, a country divided by centuries of caste, witness to some of the most horrendous ethnic violence in the world, run by a quasi-fascistic government that daily stokes the fires of communalist division, in India, the forces of division were overcome. For six days, across 200km, the exploited stood as one against their exploiters. If they can do it in India, why can’t we?

A final theme that emerges, is that of protagonism. Nowhere is there a heroic ‘savior’ to be found. While the leadership of the AIKS, are duly recognized, and characterized in a most charming and amusing way, they are not apotheosized above the marchers.

Of the forty two photographs included in the volume, only six are of the leadership. The rest document marchers sleeping out on the rocks, volunteers hauling huge basins of rice, peasants with tattered sandals and blistered feet. These are the people who made the greatest sacrifice, and they receive their due.

Overall, it is this humanizing, and historicizing that constitute the chief strengths of the volume. Especiallyin light of the media’s misrepresentation of the Long March as a parasitic, opportunistic affair, it is vital for the peasants to reclaim their narrative and let the world know what their march was really about.

It was not about getting a quick handout, but about standing up against decades of immiseration. It was not about creating chaos and disruption, but about demonstrating power in discipline. And ultimately, it was not about pitting the country against the town, but of uniting the exploited against the oppressors.

The unity that was forged between all castes, ethnicities, and religions during the march, bears testament to the power of solidarity,even in an immensely heterogenous country like India, serving as an inspiration to movements across the globe.

Despite these strengths, one glaring weakness is the silence on La Via Campesina, and the Food Sovereignty Movement as a whole. This, no doubt, has much to do with the fact that BKU (BharatiyaKisan Union) – the Indian peasant union affiliated with La Via Campesina – has ties with the RSS (Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh), an organization that holds Hitler and Mussolini amongst its pantheon, and has produced leaders like Modi, as well as many other senior figures of the BJP.

In the context of Indian politics, the RSS and BJP stand diametrically opposed to organizations like AIKS and the various communist parties of India. The relationship between AIKS and the Food Sovereignty Movement, whichconstitutesperhaps the most powerful counter-hegemonic movement in the world today, thereby becomes complicated. While no doubt, these political complexities should not overshadow the main focus of the book – the Kisan Long March – at least some mention, of the threats yet facing the movement, ought to have been included. As the former president of the Maharashtra Rajya Kisan Sabha noted in his victory rally speech, “While [the Long March] is a historic victory…there is every reasonto be vigilant” (49).

Theo V. Kenji is an aspiring agrarian sociologist and co-founder of the Radical Reading Collective at UC Irvine.